Senators in Congress are elected to represent their constituents, regardless of their personal circumstances such as income. But, with rising inequality in America an increasing concern, do Senators actually represent the preferences of both rich and poor? Using new research, Thomas J. Hayes examined the Senate’s responsiveness across a range of issues between 2001 and 2010. He finds that Senators of both parties are only responsive to their upper-income constituents, with little consideration of the needs and interests of the middle-class and the poor.

Senators in Congress are elected to represent their constituents, regardless of their personal circumstances such as income. But, with rising inequality in America an increasing concern, do Senators actually represent the preferences of both rich and poor? Using new research, Thomas J. Hayes examined the Senate’s responsiveness across a range of issues between 2001 and 2010. He finds that Senators of both parties are only responsive to their upper-income constituents, with little consideration of the needs and interests of the middle-class and the poor.

In a recent interview on “This Week with George Stephanopoulos,” President Barack Obama discussed the issue of growing economic inequality in the United States. The President, while recognizing external economic forces and globalization as contributors to growing inequality, also pointed to political factors. In the interview, the President laid much of the blame on Congress and the Republican Party:

“And the problem that we’ve got right now is you’ve got a portion of Congress who — whose policies don’t just want to, you know, leave things alone, they actually want to accelerate these trends. There’s no serious economist out there that would suggest that, if you took the Republican agenda of slashing education further, slashing Medicare further, slashing research and development further, slashing investments in infrastructure further, that that would reverse some of these trends of inequality.”

The President is rightly concerned about growing inequality, as this issue is one of the most pressing problems currently facing American society. Economic inequality has increased since the late 1970s, with gains concentrated among the top 1 percent. Even as the U.S. economy begins to recover from recession, the wealthy do markedly better than everyone else. Putting aside moral issues of basic fairness, there is evidence that high levels of inequality dampen economic growth.

But are Democrats more responsive to the preferences of poor constituents? Does a change in the partisan control of the agenda influence the way in which Senators respond to the poor? Using data from the 2004 National Annenberg Election Study (NAES), and multiple roll call votes, I examined Senate responsiveness across a range of issues for the 107th through 111th Congresses (2001 to 2010). My findings call into question the degree to which either party responds to the poor even as partisan control of the agenda changes. I find Senators of both parties are responsive to upper-income constituents, yet they are unresponsive to poor constituents.

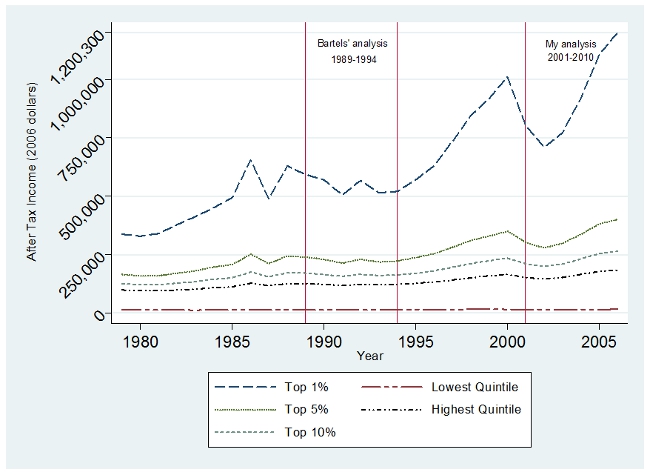

Building on the work of Larry Bartels in Unequal Democracy, I examined responsiveness in the U.S. Senate during a time in which inequality increased substantially, which can be seen in Figure 1 below. This figure shows the degree to which incomes are unequal for different quintiles of Americans. As the figure shows, those in the three lowest quintiles (the bottom 60 percent) have seen little change over time. However, most of the dramatic gains in income have gone to the highest quintile. Moreover, among the top quintile, incomes have increased dramatically for the top one and five percentiles.

Figure 1 – Inflation Adjusted Household Incomes (After-Tax), 1979-2006

Source: Congressional Budget Office

The period for which I examine Senate responsiveness is during a time in which the Republican Party controlled the Senate and had unified control of the government for almost the entire period for the 107th, 108th, and 109th Congresses (2001-2006). By including the 110th and 111th Congresses (2007-2010), it is possible to examine a period for which the Democratic Party controlled the Senate. Also, the inclusion of the 111th Congress allows for a view of the Senate when the Democratic Party had unified control of the government, as the 2008 election produced large gains in both chambers of Congress as well as Barack Obama winning the presidency.

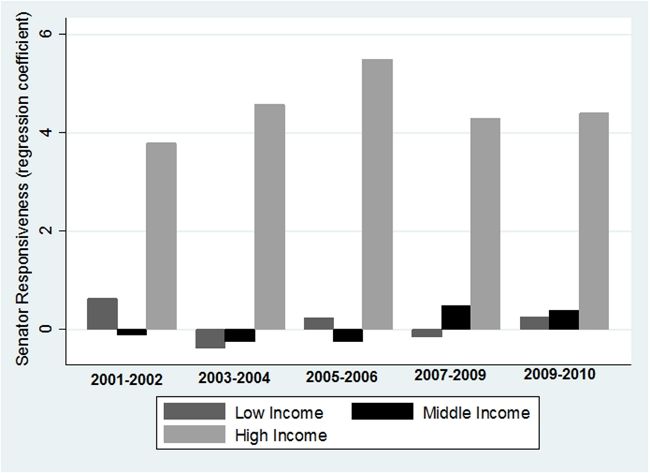

To examine responsiveness of Senators, I separated constituents into income groups of low, middle, and high income. I then compared Senator responsiveness to the preferences of their constituents and found some striking results, displayed in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – Senators’ Responsiveness to Income Groups (107th-111th Congresses)

The figure shows the resulting regression coefficient (which measures responsiveness) from my analysis. As Figure 2 demonstrates, Senators are found to be positively responsive to Upper-Income Constituents, and only slightly or negatively responsive to Lower or Middle-Income Constituents. This is true regardless of which party is in control of the Senate.

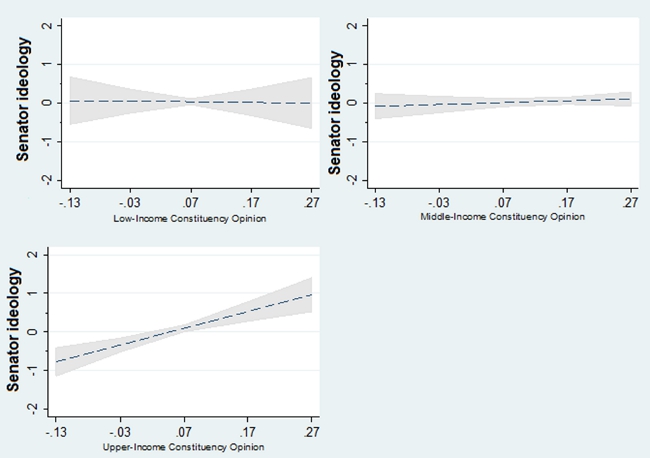

The nature of unequal responsiveness can be seen in Figure 3, which displays the predicted responsiveness for Senators in the 110th Congress (2007-2009) to each income group. The y-axis displays Senator ideology and the x-axis shows constituent preferences. In the figure, the dotted line represents the predicted values, while the shaded area shows the 95 percent confidence interval. As the figure shows, the predicted responsiveness for both Lower and Middle-Constituency Opinion is flat, while the responsiveness toward Upper-Income constituency opinion is positive.

Figure 3 – Predicted Senator Responsiveness by Economic Class for 110th Congress (2007-2009)

While responsiveness to Upper-Income Constituents is constant, (even when controlling for other factors), there is little difference in responsiveness between Democrats and Republicans. In fact, the single finding of a partisan bias in responsiveness comes in the form of Republicans responding to the desires of the middle-class more than Democrats in the 109th Congress. In no instance was I able to detect either party to be more responsive to the preferences of the poor.

Does Partisan Change in the Control of the Agenda Increase Responsiveness?

The 107th Senate (2001-2002) presents an interesting and rare opportunity to test the degree a change in the nature of issues on the agenda (and which party control the agenda) can influence the way in which legislators respond to different income groups. At the beginning of the 107th Senate session, the Republican Party had unified control of the government. While the Senate was effectively split evenly between the parties with fifty members from each party elected, Republican control of the Presidency gave Vice President Dick Cheney the tie-breaking vote in the Senate, and thus majority control of the chamber. This changed on May 26th, 2001 after Senator Jim Jeffords (R-VT) announced he was changing his party affiliation to an Independent and would caucus with the Democrats, thus handing them control of the chamber.

Jeffords’ switch presents an interesting case study to test the effects of a change in partisan control on legislator responsiveness toward different income groups. This is an opportunity in which we can examine the same group of legislators during a similar time period in which partisan control of the agenda changes. The results for this analysis show that partisan control of the agenda matters, but not the way we might suspect, as I find overall responsiveness toward upper-income constituency opinion is greater once Democrats take control of the chamber.

The findings from my study do not provide evidence that the policies pursued by the Republican Party would do a better job at combating growing inequality than those of the Democratic Party. One only needs to compare the recent passage of health care reform by the Democrats to efforts of the Republican controlled House to cut food stamps to see partisan differences in legislation aimed at helping the poor. But growing economic inequality, coupled with a decline in campaign finance laws, should lead us to question the degree to which politicians respond to the needs and interests of the poor in a New Gilded Age, even if Democrats are in control of the agenda.

Featured image credit: Tricia (Creative Commons BY SA)

This post is a longer version of ‘Responsiveness in an Era of Inequality The Case of the U.S. Senate’, which appeared in the September 2013 of Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1dTZsBU

_________________________________

Thomas J. Hayes – University of Connecticut

Thomas J. Hayes – University of Connecticut

Thomas J. Hayes is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Connecticut. He specializes in the fields of American politics and political behavior, with an emphasis on economic inequality. His current research projects examine the degree to which institutional decisions influence attitudes toward disadvantaged groups, the factors that lead states to adopt an income tax, the electoral components that lead to unequal representation, and the reasons that states adopt voter identification laws.