It is well known that older people tend to be stronger supporters of their chosen political party than their younger counterparts. Elias Dinas uses data from the Socialization Panel Study to test the idea that the actual act of voting strengthens party identification. He concludes that consonant votes strengthen partisanship and discusses the specific implications of these findings on future elections in the US.

It is well known that older people tend to be stronger supporters of their chosen political party than their younger counterparts. Elias Dinas uses data from the Socialization Panel Study to test the idea that the actual act of voting strengthens party identification. He concludes that consonant votes strengthen partisanship and discusses the specific implications of these findings on future elections in the US.

It is probably safe to argue that party identification (PID) is by far the most studied phenomenon among students of electoral politics. Originally developed in the late 1950s, the concept refers to a sense of belonging to a political party, an affective attachment, without this being necessarily combined by any formal party membership. PID is particularly important because partisans are deemed to perceive the news, the state of the economy or to evaluate parties’ stances and leaders’ integrity differently than independents. In general, PID is assumed to color all aspects of one’s political life. Moreover, given that it closes the gap between the political elites and the masses, it has been argued that high levels of partisanship help the process of democratic consolidation. For instance, it has been argued that one of the reasons for the rise of Nazism in Germany has been the lack of strong partisan ties during the Weimar regime.

The question that arises is how do we acquire this sense of belonging with a political party? What makes us partisans? What drives us to the point to call ourselves either Democrats or Republicans? The answer to this question is still unclear.

For one thing, we know that children tend to acquire the partisan preferences of their parents. Still, although in childhood this transmission process might be nearly perfect, it fails to resemble the picture of a photographic reproduction once the offspring begins its own involvement into politics. Moreover, looking at different political periods and generations, we know that older people tend to be stronger supporters of their party than younger people. Why this is the case, however, remains both theoretically and empirically under-investigated.

At least in part the answer to the question of how partisan ties develop is through the act of voting in presidential elections. In other words, our voting behavior influences our political opinions and identities. To be sure, the idea that there is a feedback loop from behavior to attitudes is nothing but new among cognitive psychologists. Take the following example. In a classic experiment run by social-psychologist Jack Brehm (1956), subjects were given a series of appliances, which they had to rate. Subjects who rated equally two objects were asked to choose one of the two. Twenty minutes after having done so, they were called to rate the items again. Interestingly, in this second round, individuals rated the chosen appliance higher than the alternative they elected not to take home.Elections work in a similar way. The manifestation of a preference into an actual behavior creates a sense of commitment, which intensifies prior preferences and in so doing it fosters group identities. Voting for a party makes people perceive themselves as prototypical supporters of their party of choice. Thus, casting a vote that is consonant with one’s prior preference should strengthen prior partisan ties, whereas a dissonant vote should weaken them. The aggregate increase in partisan strength along aging is thus the result of the fact that consonant votes outweigh dissonant ones.

Testing this idea empirically becomes difficult because in free elections people tend to vote for the party they like most. Imagine we interview people after the 2012 Presidential election and we find that Obama voters are more strongly attached to the Democrats than non-voters or Romney voters. Attributing this difference to the act of voting is of course problematic. It seems more likely that Obama voters were already stronger supporters of the Democrats before the election and this is also why they also voted for this party’s candidate. In other words, testing the impact of electoral participation on the development of party identification requires a setting in which we can compare a group of voters with a group of individuals of otherwise similar political outlooks differing only in that for some reason they could not manifest their preference into an actual vote.

Such a setting is provided by the Socialization Panel Study, which traces a specific year cohort over more than three decades. The first wave of the study appears in 1965 with a random sample of high-school seniors, almost all of them born between 1947 and 1948. These young respondents are re-interviewed in 1973; in 1982; and in 1997. The important feature of this study is that it allows us to construct two groups of minimal age difference of whom only one was eligible to vote in the 1968 election. Thus, assuming that the actual date of birth is not driven by considerations of 1968 vote eligibility, we can treat the two groups as otherwise similar.

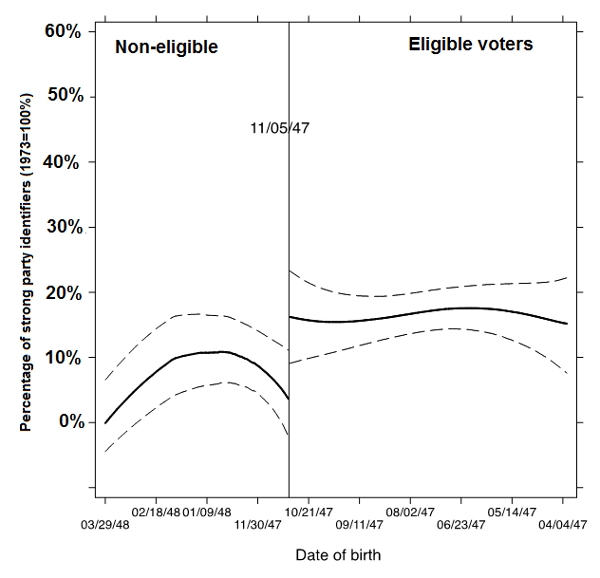

Figure 1 shows the percentage of strong identifiers in 1973 among non-eligibles and eligibles, respectively, sorted according to their date of birth. There is a gap in strength of PID at the eligibility threshold. On average, eligibles appear to be more likely to register strong partisan views than non-eligibles. Whereas 9.5 per cent of non-eligibles declared a strong attachment either to the Democrats or the Republicans, the equivalent figure for eligibles is 16.8 per cent.

Figure 1: Percentage of strong identifiers in 1973 according to their date of birth.

(Note: The solid bold curves present the local average of partisan strength, conditional on date of birth. The dashed lines display the 95 % bootstrapped confidence intervals. The vertical line denotes the date of birth cutpoint that determines eligibility status (November 5, 1947). Individuals are sorted from younger to older.)

To be sure, people who are eligible to vote may become more informed about the coming election since they are more easily targeted by the parties, or pay more attention to the campaign. If this is the case, then elections might not operate through the psychological process hypothesized here but as a funnel of political information. However, further tests rule out this possibility, since eligibles do not seem to become more knowledgeable and politically interested than non-eligibles.

Importantly, the effect seems to match the direction of one’s vote choice. Democratic voters become stronger Democrats and Republican voters become more Republican. In general, consonant votes strengthen partisanship, whereas dissonant votes weaken it. These effects seem to last at least until 1982, when our high-school seniors were approximately 35 years old. No difference is observed, however, by 1997, when the two groups are approximately 50 years old. This finding gives credit to the idea that political identities are typically formed during the period of early adulthood, which means that one’s elections during this period might be particularly formative.

The last point brings us to the more specific implications of this finding about the dynamics of party competition in the US. Obama dominated the young vote both in 2008 and in 2012. In so doing, he has created a generation of long-life Democrats. To be sure, such electoral effects might not be strong enough to outweigh other influences that may turn Obama voters away from the Democratic Party. That said, the presence of long-term voting effects make the Obama vote a non-trivial asset for the party’s electoral fortunes in the future.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Does Choice Bring Loyalty? Electoral Participation and the Development of Party Identification‘ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1gKaJWQ

_________________________________

Elias Dinas – University of Nottingham

Elias Dinas – University of Nottingham

Elias Dinas is a lecturer in the social sciences at the University of Nottingham. His research interests primarily focus around political socialization and on the formation and crystallization of political attitudes and partisan identities.

I can attest this. I’ve leaned Democrat most of my life. I moved into a very Republican district in Texas. Most of the local elections are decided in the primaries; the Democrats aren’t competitive here. I decided to vote in the Republican primaries, voting for the best (usually, the most moderate) candidate. In the 2008 election, I voted for McCain in the primary. Even after the twin fiascoes of him shutting down his campaign, and him choosing Palin as VP, I found it very difficult to change my vote to Obama. Voting for him in the primary seemed like a commitment which I was loathe to abandon.