At the end of 2008, the newly elected President Barack Obama was facing one of the deepest economic crises in living memory. Jared Bernstein, a former member of the President’s economic team, looks at the successful and not-so-successful policy measures taken by the Obama Administration to deal with effects of the Great Recession. He writes that while 2009’s Recovery Act did help to diminish job and real GDP losses, he also argues that the government undertook fiscal consolidation too early.

At the end of 2008, the newly elected President Barack Obama was facing one of the deepest economic crises in living memory. Jared Bernstein, a former member of the President’s economic team, looks at the successful and not-so-successful policy measures taken by the Obama Administration to deal with effects of the Great Recession. He writes that while 2009’s Recovery Act did help to diminish job and real GDP losses, he also argues that the government undertook fiscal consolidation too early.

Like so many great American stories, this one begins in Chicago, in December 2008. That was the first meeting of President-elect Barack Obama’s economics team, of which I was extremely privileged to be a member. With the snow swirling outside, for the first time, the team convened in an office building at a rectangular table with the President- and Vice-President-elect at the head.

I suspect I’m not just speaking for myself when I tell you that the mood was an intense combination of excitement and dread. On the one hand, there we were with an historic, brilliant President-elect coming off of a successful campaign built on an inclusive economic message that resonated deeply with many Americans for whom years of growth had been little more than a spectator sport.

On the other hand, while we didn’t yet have all the numbers, we knew the economy was in a lot of trouble. The housing bubble had burst, foreclosures were mounting, a deep deleveraging cycle was reversing wealth effects that had fueled the expansion—in a word, we knew we were in the midst of a very steep demand contraction and credit crunch.

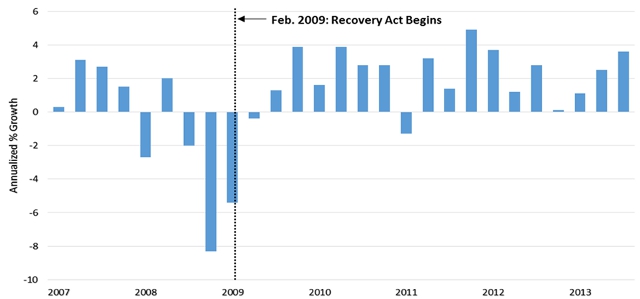

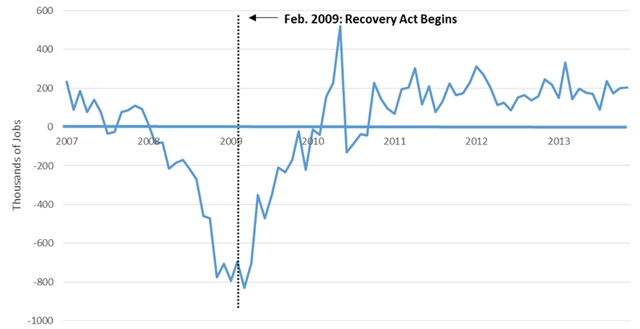

But we didn’t know how deep. As it turns out, while we were sitting in the conference room, the economy was contracting by a real annual rate of 8.3 percent, a rate of decline almost unprecedented since our Great Depression (see Figure 1, below). In the next month, when the President took up residence at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, employment fell by almost 800,000; in fact; payrolls contracted by 2.3 million jobs in the first quarter of 2009, a decline of almost 2 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 1 – Real GDP growth, 2007 – 2013

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Figure 2 – Monthly Job Changes 2007 – 2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The measures we took are by now well-known, if not well-understood. If credit is the bloodstream of modern, capitalist economies, and demand is the heartbeat, we were dealing with a patient with dangerously low blood pressure and a very weak heart. Measures taken under President Bush to reflate the banking system were extended and expanded and the Recovery Act—a large Keynesian stimulus—was enacted. And of course, the Federal Reserve also stepped up with aggressive monetary stimulus.

Economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi undertook the most comprehensive review of the impact of these measures, and their title suggests their conclusion: How the Great Recession Was Brought to an End.

In this paper, we…simulate the macroeconomic effects of the government’s total policy response. We find that its effects on real GDP, jobs, and inflation are huge, and probably averted what could have been called Great Depression 2.0. For example, we estimate that, without the government’s response, GDP in 2010 would be about 11.5 percent lower, payroll employment would be less by some 8½ million jobs, and the nation would now be experiencing deflation.

That’s the statistical evaluation. If you want a truly excellent read of the full spate of politics and policy around the Recovery Act, you have to read Michael Grunwald’s “The New, New Deal.”

But both documents tell a similar story, one of at least limited policy success. There are, of course, opposing views—this is, after all, economics, and it’s also America in a period of stark political divisions. But the consensus among most economists is in line with the above.

In fact, a quick glance at some very basic figures tell the story. Following the enactment of the Recovery Act, the rate of both job and real GDP losses diminished. The latter turned positive by the third quarter of 2009, and the former about a year later. Of course, such simple charts don’t prove causality by a long shot. But in tandem with the econometrically rigorous work cited above, I’d argue that a close shave with Occam’s razor would support the message of the figures.

What might we have done differently?

First, like the UK and Europe, U.S. fiscal policymakers—as distinct from those at the Federal Reserve—embraced austerity measures well before their time. Our budget deficit fell from 10 percent of GDP in 2009 to 4 percent this year, the largest four-year decline since 1950. There is, of course, a time for such fiscal consolidation, but if there’s one lesson from recent policy mistakes across the globe, it is that doing so prematurely is a serious economic mistake.

Second, perhaps because of the desire to pivot from Keynesian stimulus to deficit reduction, we were too quick to identify phantom economic “green shoots:” signs that the recovery was taking hold before that was truly the case.

Third, the more directly stimulus measures are tied to job creation the better, and that militates against devoting too many resources to tax cuts. About one-third of the Recovery Act went to lowering taxes, and there’s a slip between the cup and the lip there. Instead of boosting consumer spending, tax cuts can be used to boost savings and pay down debt (venerable purposes, but not stimulative), and they can leak out on imports.

Fourth, and I’m not sure we or anyone else could have done a better job at this, we were not particularly effective in selling the impact of the Recovery Act to the nation. Basically, the problem is that normal humans, as opposed to economists, don’t do “counterfactuals.” We passed the Recovery Act, and things kept getting worse for a while. They got worse at a slower rate, as you can see in the figures above, and as the research confirmed, things would have been worse without the stimulus. But I don’t care how skilled a politician you are, “things coulda been worse” is not a winning message.

At any rate, 20/20 hindsight is a wonderful thing. Yet even with those mistakes, I’m still proud of the work we did to hit back against the Great Recession. I only hope that future policymakers learn from what went right and what didn’t.

This article is based on Jared Bernstein’s recent event at the Resolution Foundation, “What’s the damage? The impact of the great recession on the jobs market in Britain and America — and the prospects for a recovery”.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/19PpjXV

_________________________________

Jared Bernstein – Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Jared Bernstein – Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Jared Bernstein is a Senior Fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. From 2009 to 2011, Bernstein was the Chief Economist and Economic Adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, executive director of the White House Task Force on the Middle Class, and a member of President Obama’s economic team. Bernstein’s areas of expertise include federal and state economic and fiscal policies, income inequality and mobility, trends in employment and earnings, international comparisons, and the analysis of financial and housing markets. Prior to joining the Obama administration, Bernstein was a senior economist and the director of the Living Standards Program at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. Between 1995 and 1996, he held the post of deputy chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor.

2 Comments