The 2008 election which saw President Barack Obama elected was hailed as the first ‘Facebook election’. But was Facebook really a ‘hotbed’ for political activity in that election? Using data from questionnaires and Facebook profiles, Juliet Carlisle and Rob Patton take a close look at the nature of political engagement on Facebook during the 2008 election. They find that the variables that are known to predict political participation in the offline world, such as sex and parental income, are not predictors of political activity in the Facebook environment. They also find, surprisingly, that those with more friends and who belong to more Facebook groups are less likely to be politically active.

The 2008 election which saw President Barack Obama elected was hailed as the first ‘Facebook election’. But was Facebook really a ‘hotbed’ for political activity in that election? Using data from questionnaires and Facebook profiles, Juliet Carlisle and Rob Patton take a close look at the nature of political engagement on Facebook during the 2008 election. They find that the variables that are known to predict political participation in the offline world, such as sex and parental income, are not predictors of political activity in the Facebook environment. They also find, surprisingly, that those with more friends and who belong to more Facebook groups are less likely to be politically active.

We live at a time of transformational media. Social media in particular has captured both the popular attention and the attention of scholars who study political engagement. With approximately 1 billion users Facebook has played a role in the last two U.S. Presidential elections. Despite popular accounts illustrating the ability of social media to mobilize users for political activity, little empirical work has measured the nature of political engagement occurring within social networking sites. The 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, often regarded as the first Facebook election, offers an excellent opportunity to address this topic.

Using data compiled from university student questionnaires, school records, and the students’ Facebook user profiles (text, images, applications, correspondence, etc.) throughout the 2008 election cycle; we looked at the level of political participation of college undergraduates and recent graduates in Facebook. We considered whether the antecedents that predict offline participation also predict online participation; and the extent to which users engaged themselves over the course of the 2008 primary and general elections.

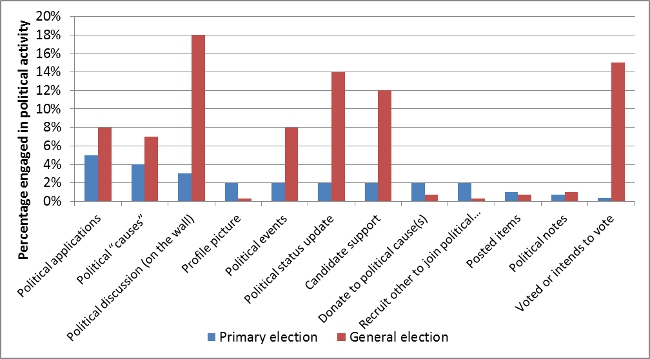

We created a simple additive index of political activity (0–12) constructed from thirteen dichotomous variables that indicate whether the participant engaged in a particular political activity (see Figure 1). A high score indicates the individual is more politically active. Traditional measures of participation suggest that Facebook users will be more active politically at general elections than at primary elections. Indeed, according to the results of our independent-samples t-test, participants had a level of political activity six times higher for the general election than the primary.

Figure 1 – Political Activity on Facebook Primary and General Elections

Differences exist for particular types of political participation between the two elections. For the primary election, Figure 1 illustrates low levels of political activity with only 0.4 percent of the sample voting or intending to vote during the primary. However, during the general election Facebook users are more politically active with the proportion participating in political discussion jumping more than 15 percent from the primary to the general election.

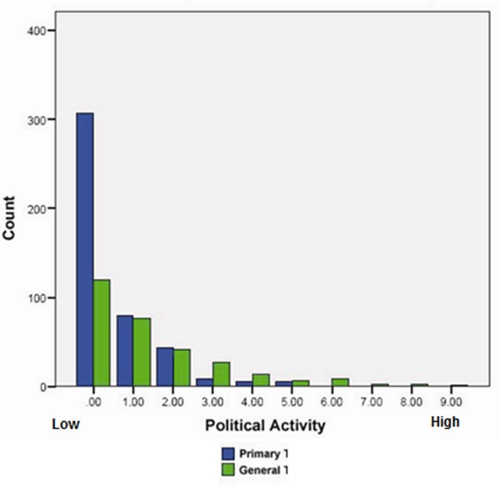

Figure 2 below also demonstrates that in 2008 Facebook was not the hotbed of political activity that popular accounts may have us believe. During both the primary and general elections, users were more likely to be nonactive politically than they were to be politically active. Nevertheless, we do see that several types of political activities increased over the course of the election.

Figure 2 – Frequency of political activity during the primary and general elections

We also considered a set of standard predictors, including those associated with two theories of participation, on our political activity index. We then modelled and compared the differences that the predictors might have for the different elections. Specifically, we compared predictors associated with the resource model against those of network size à la Putnam. Our results demonstrate that many of the variables considered usual suspects and likely contributors to political participation do not carry the same relationship to political activity in a Facebook environment. For example, two of the “big three” standard predictors of political activity (sex and parental income) are not significantly related to political activity in Facebook and race is only significant for the primary election.

The resource model of political participation predicts that income and interest drive political participation. Our findings are mixed. Parental income lacks statistical significance. Nevertheless, the impact of political interest is positive and significant so that those Facebook users who are more interested in politics are more likely to participate via Facebook during both elections. Overall, political interest has the strongest impact of all the predictors. Also, it is worth including race with our discussion of the resource model as race is often correlated with factors that drive participation. Our results demonstrate that for the primary election, nonwhites are more likely to be politically active than are whites. The effect of race is insignificant for the general election, however.

Using Putnam’s social capital framework, we predict a positive and significant relationship between network size (number of friends and group membership) and political participation. We find that the number of Facebook “friends” a user has is not significantly related to political participation. Moreover, our results demonstrate the direction of the relationship to be opposite of our expectations so that those with more friends and who belong to more Facebook groups are less likely to be politically active. This suggests that collecting friends or building one’s social network by joining groups in Facebook is an independent activity undertaken by users less inclined to be politically engaged with that network. Facebook “friends” and network do not seem to offer the same sorts of benefits that real-life friends do in terms of developing the type of social capital needed to nurture political engagement. Like resource theory, our support for Putnam’s theory is mixed.

Our findings suggest that Facebook political engagement may be unique in that very few of the traditional predictors of offline political engagement carry over to the social media space. While many tend to view the Internet and new technologies as tools that can easily enrich and nourish civic and political life, research has mainly revealed that existing inequalities in real life are translated and carried over into online life creating a digital divide. We find that some traditional predictors that create differentials in political engagement, most notably parental income, sex, and race/ethnicity, do not appear relevant in Facebook. And, if they do (e.g., race), they tend to benefit those who are generally less likely to participate (e.g., minorities). We find this to indicate that perhaps Facebook is leveling the playing field and allowing those who might lack the resources to participate in a conventional sense, the ability to participate in a digital sense.

As citizens, campaign strategists, and candidates become more familiar with how to use Facebook as a tool for political engagement, it is likely that Facebook will become more embedded into the political landscape. As the ranks of active political Facebook users become more established in the long term, we anticipate that Facebook and social media in general will play more of a role in how we conceptualize political engagement.

This article is based on the paper, Is Social Media Changing How We Understand Political Engagement?in the December 2013 issue of Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/18wZQHK

_________________________________

Juliet Carlisle – University of Idaho

Juliet Carlisle – University of Idaho

Juliet Carlisle is an Assistant Professor of political science at the University of Idaho. Her research substantively deals with political participation, public opinion, and political socialization. Her most current projects include a co-authored book manuscript, The Politics of Energy Crises, and work exploring public attitudes toward large-scale solar developments in the U.S., which is funded by a $2.7 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Rob Patton – University of Idaho

Rob Patton – University of Idaho

Rob Patton is a digital marketing and social media strategist. Rob has spent several years as a new media consultant developing online advocacy and mobilization plans for political candidates and issue-oriented campaigns across the U.S. He currently serves as the Marketing Communications Manager for the College of Engineering at the University of Idaho.