The Democratic Party is characterized by its willingness to increase government spending to pursue their policy goals. However, when they do make cuts, Democrats tend to make more large cuts than Republicans. Sarah E. Anderson and Laurel Harbridge use data from U.S. budgetary spending reports from 1955-2002 to explain this paradox, arguing that Democrats make cuts as corrections to balance prior partisan decisions.

The Democratic Party is characterized by its willingness to increase government spending to pursue their policy goals. However, when they do make cuts, Democrats tend to make more large cuts than Republicans. Sarah E. Anderson and Laurel Harbridge use data from U.S. budgetary spending reports from 1955-2002 to explain this paradox, arguing that Democrats make cuts as corrections to balance prior partisan decisions.

An empirical investigation of the U.S. budget reveals a puzzling pattern of spending. When they do make cuts, Democrats make more large cuts than Republicans. This is exactly the opposite of what we would expect from their ideological stances, but can be explained if these large changes are made as corrections to prior increases in spending rather than ideologically motivated cuts.

Just like each of us, legislators have limited time to process the overwhelming amount of information that enters the policymaking process. In the face of this barrage, they use shortcuts, like uncritically pursing their partisan goals. In the realm of domestic spending, Democrats prefer to increase spending and Republicans prefer to cut it. This is borne out empirically among year-to-year domestic discretionary spending patterns: Democrats increase spending, while Republicans make cuts. Yet sometimes they must make corrections to these partisan courses—either in response to an obvious signal from the world around them or to correct a series of partisan decisions that have resulted in spending that is too low or too high. We call this motivated information processing, it is based on ideas about motivated reasoning and disproportionate information processing. It results in an increase in large cuts to spending when Democrats control more of the lawmaking institutions.

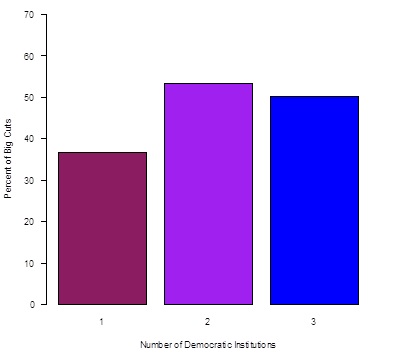

Figure 1: Distribution of Budgetary Cuts Note: Y-axis measures the percent of subaccount cuts that fall into the big cut category (greater than 50%). Only subaccounts that fall under Democratic issue ownership are included.

Note: Y-axis measures the percent of subaccount cuts that fall into the big cut category (greater than 50%). Only subaccounts that fall under Democratic issue ownership are included.

These large cuts are especially prevalent on their own pet issues, like social and environmental issues. These are exactly where we’d expect them to employ partisan reasoning most and to have to make the corrections. The cuts are also more prevalent in off-election years, when lawmakers are less likely to face the wrath of their supporters after they make the corrections. Our analysis of U.S. budgetary spending from 1955-2002 reveals that increasing Democratic control from one lawmaking institution to unified control (control of the Presidency, House, and Senate) corresponds to a 5% increase in the likelihood of a big cut in spending. Among just those policies that are most closely associated with the Democratic Party, the change in the likelihood of a big cut when moving from one branch of Democratic control to unified Democratic control increases to 13%.

The case of environmental spending on federal land acquisition in early 1990s exemplifies the pattern predicted by our framework and seen in the empirical results. Democrats, as the more pro-environmental party, were typically more willing than Republicans to add land to the public domain. It was only when faced with very compelling information that additional spending on public lands would jeopardize commitments to existing federal land management that Democrats agreed to cut spending on land acquisition. In 1993, after increasing the budget in four out of the prior five years, the unified Democratic government made a drastic cut to the Bureau of Land Management land acquisition subaccount. It took until 2000 to reach the 1992 level of spending again.

These patterns of spending changes are further evidence that parties play a crucial role in producing policy. In particular, they structure the goals of their members, which can affect what types of information is considered or ignored in policymaking. Partisanship manifests in intuitive ways, with more Democratic control associated with more increases to spending on various programs. But it also manifests in less obvious ways when the accuracy goals of policymakers drive them to make large corrections that result in large cuts to budgetary subaccounts when Democrats control more institutions of government. This counterintuitive pattern becomes predictable when we realize that lawmakers, just like the rest of us, are subject to bias but also want to make good public policy.

This post is based on the forthcoming article “The Policy Consequences of Motivated Information Processing among the Partisan Elite,” which will appear in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/18XUbZj

_________________________________

Sarah E. Anderson – University of California, Santa Barbara

Sarah E. Anderson – University of California, Santa Barbara

Sarah E. Anderson is an Assistant Professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research interests include the role of political parties, bureaucratic delegation, and environmental politics.

_

Laurel Harbridge – Northwestern University

Laurel Harbridge – Northwestern University

Laurel Harbridge is an Assistant Professor at Northwestern University and a Faculty Fellow with the Institute for Policy Research. Her research interests include the United States Congress, congressional elections, political parties, and public policy.