With the 2014 mid-term elections looming ever closer, it is only a matter of time before the calls for candidates to have greater dialogue on issues begins. But is this dialogue, or ‘issue convergence’ helpful for voters? New research by Keena Lipsitz into what happens when candidates address the same issues at the same time finds that individuals hear from both candidates, they are often easily confused, especially if their level of political interest is not high.

With the 2014 mid-term elections looming ever closer, it is only a matter of time before the calls for candidates to have greater dialogue on issues begins. But is this dialogue, or ‘issue convergence’ helpful for voters? New research by Keena Lipsitz into what happens when candidates address the same issues at the same time finds that individuals hear from both candidates, they are often easily confused, especially if their level of political interest is not high.

A perennial campaign season lament is that candidates “talk past” one another instead of engaging one another on the issues. The assumption is that this lack of “dialogue”–or what political scientists call “issue convergence”–makes it difficult for citizens to compare the candidates’ positions and, thus, to make informed decisions on Election Day. Yet my recent research suggests this conventional wisdom may be off the mark. In fact, issue convergence is as likely to harm citizens as it is to help them, especially if those citizens are not especially interested in politics. These individuals seem to get confused when they hear both candidates discussing the same issue. They also appear to be more easily misled than politically interested people by candidate misinformation.

To show this, I collected all of the ads aired by the presidential candidates in the 2000 and 2004 general election campaigns. The Wisconsin Advertising Project (WAP) provides the storyboards of the ads with their transcripts so I was able to identify which Democratic and Republican ads discussed the same issues. When I found an issue that both candidates discussed, I then used another WAP dataset to determine if both candidates aired ads about that issue in the same television media market. A media market is a group of counties in which the residents watch the same television stations. In 2000 and 2004, I found media market-level issue convergence on three issues: prescription drug coverage for seniors (2000); investing social security in the stock market (2000); and expansion of health insurance coverage (2004).

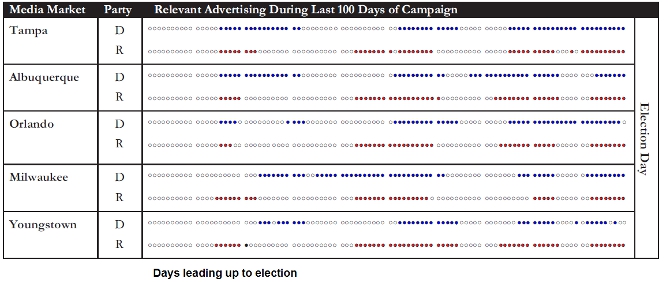

Figure 1 below illustrates what the advertising about health insurance expansion looked like in five media markets in the last 100 days of the 2004 campaign. Notice that there was a great deal of overlap In the Kerry and Bush ads about the topic: this is the kind of dialogue I am interested in. I then used the National Annenberg Election Study, a massive national survey that interviewed approximately 300 Americans a day in 2004 (and 2000) to see if people learned more about the candidates’ positions on the issue when: just one of the candidates was airing ads about the issue; both were airing ads about the issue; or when they were both silent about on the topic. I followed this same procedure for the other two topics as well.

Figure 1: Democratic and Republican Advertising about Health Insurance during 2004 Campaign in 5 Media Markets

Source: Wisconsin Advertising Project and the Campaign Media Analysis Group. “D” indicates Democratic advertising and “R” indicates Republican advertising. The dots each represent one of the last 100 days of the campaign (from July 25th to November 1st) with “●” indicating a day on which health insurance ads were aired and “○“ indicating that no health insurance ads were aired. These media markets saw the most advertising about this issue.

In two cases, the issues of investing social security in the stock market and expanding health care coverage, people with lower political interest learned from Republican ads in the absence of Democratic ads. But when Gore and Kerry began to run ads on the same subject, the positive effects of the Republican ads disappeared. This might suggest that the Democratic ads were misleading, but they were not harmful to voters when Bush was silent about the issue; the negative effects were only observed when both candidates were talking about it. In the final case, I did identify an issue where hearing from both candidates about an issue helped voters more than if they had heard from only one of the candidates. Unfortunately, it was because one candidate’s ads misrepresented the other candidate’s position. When the attacked candidate responded, it mitigated the harmful effects of the attacker’s ads.

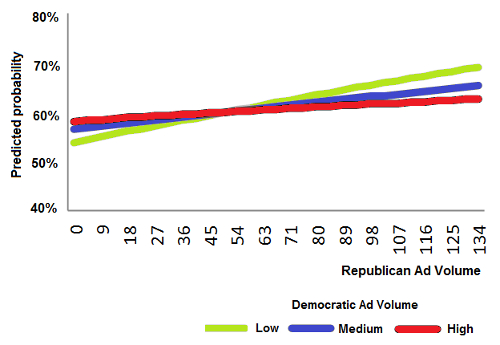

In the case of dialogue concerning the investment of social security funds in the stock market, Bush’s ads clearly stated his plan, “gives younger workers a choice to put their Social Security in sound investments they control for higher returns.” Gore’s ads ignored his own position, focusing instead on Bush’s. For example, his most aired ad (3700 times) said Bush was, “promising to take a trillion dollars out of Social Security so younger workers can invest in private accounts” but, he added, “The problem is that Bush has promised the same money to pay seniors their current benefits.” One would think that people could learn Bush’s position from Gore’s ad as well and evidence suggests that exposure to Gore’s ads in the absence of Bush ads certainly was not harmful. Yet, when individuals heard from both candidates, the positive effects of Bush’s ads disappeared altogether, as Figure 2 below illustrates.

Figure 2: Probability respondent knows Bush position on investing in social security and level of Democratic and Republican advertising

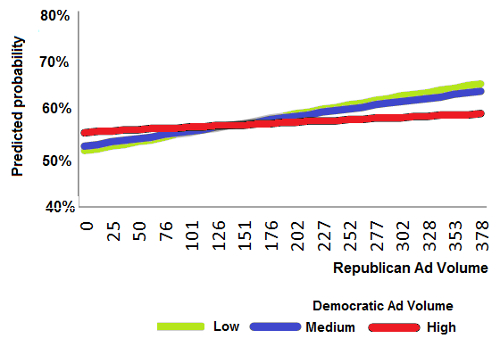

Issue convergence had the same effect in the case of Bush and Kerry’s positions on expanding access to health insurance. Both candidates focused more attention on Kerry’s position. While Kerry’s ads emphasized his belief that health care should be a right for all citizens, Bush aired 5 different ads (aired more than 20,000 times) that characterized Kerry’s plan as, “a big government takeover” that would lead to “rationing, less access, fewer choices, long waits,” and would involve “the IRS, Treasury Department, and several massive, new government agencies”. Ironically, the evidence suggests people learned more about Kerry’s position from Bush’s ads than his own, but again, this was only in the absence of Kerry’s ads. When individuals with less political interest heard from both candidates, the beneficial effects of the Republican ads disappeared.

Figure 3: Probability respondent knows Kerry wants to provide more health insurance in social security and level of Democratic and Republican advertising

In the case of Bush and Gore ads discussing the provision of prescription drug coverage to seniors in the 2000 campaign, the research uncovers evidence that issue convergence can be beneficial for citizens, but only because Gore’s ads mitigated the harmful effects of Bush’s ads.

In the ads, both candidates spent more time talking about Gore’s position. Although Gore planned to cover prescriptions through an expansion of Medicare, Bush’s ads claimed Gore’s plan would force “seniors into a government-run HMO” and would let, “Washington bureaucrats interfere with what your doctors prescribe.” Gore fought back with an ad that said, “Newspapers say George Bush’s prescription drug ad misrepresents the facts,” and assured viewers that his plan, “covers all seniors through Medicare, not an HMO. Under Gore, seniors choose their own doctor and doctors decide what drugs to prescribe.” The research suggests, as one might expect that people with less political interest who heard Bush’s ads in the absence of Gore’s ads were unable to correctly identify Gore’s position. If they heard from both candidates, however, the harmful effects of the Republican ads disappeared.

Figure 4: Probability respondent knows Gore’s position on prescription drug coverage for seniors and level of Democratic and Republican advertising

So does this mean that it is better for voters if candidates talk past one another? I would not go that far. We saw an instance here where it was clearly helpful for voters to hear from both candidates. But my research does suggest we should not be surprised if issue convergence and negativity occur together; when candidates begin to gain traction with citizens on a particular issue their opponents often see no option but to attack them on that issue. Ideally they would do this by laying out their own position and explaining why it is superior, but this research underscores what we already know: reality is far from ideal.

This article is based on the paper ‘Issue Convergence Is Nothing More than Issue Convergence’ in the December 2013 edition of Political Research Quarterly, which will be be open access until February 9th.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1axWbox

_________________________________

Keena Lipsitz – Queens College, CUNY

Keena Lipsitz – Queens College, CUNY

Keena Lipsitz is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Queens College, City University of New York. Her main field is American political behavior with a focus on how political campaigns affect voters, but she has broader interests in democratic theory, public opinion, election law, and media effects as well. She is the author of Competitive Elections and the American Voter and a co-author of Campaigns and Elections: Rules, Reality, Strategy and Choice.