Last July, the city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy, the largest municipality to do so in U.S. history. But was this action avoidable? With this in mind, John F. McDonald takes an in-depth look at the city’s history. He argues that the seeds of Detroit’s problems can be traced back to the 1950s, and the subsequent slow decline of the automotive industry, the city’s population, employment and revenues, together with rising public liabilities, made bankruptcy all but inevitable.

Last July, the city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy, the largest municipality to do so in U.S. history. But was this action avoidable? With this in mind, John F. McDonald takes an in-depth look at the city’s history. He argues that the seeds of Detroit’s problems can be traced back to the 1950s, and the subsequent slow decline of the automotive industry, the city’s population, employment and revenues, together with rising public liabilities, made bankruptcy all but inevitable.

The City of Detroit, Michigan filed for bankruptcy on 18 July 2013, and a federal judge ruled in December that the bankruptcy proceedings would commence. The City of Detroit had been running deficits for ten years caused be declining tax revenues, withdrawal of financial support from the State of Michigan and the federal government, and expenses that were not reduced rapidly enough. The Governor of the State had appointed an Emergency Manager for the city in April 2013, who quickly realized that the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history could not be avoided.

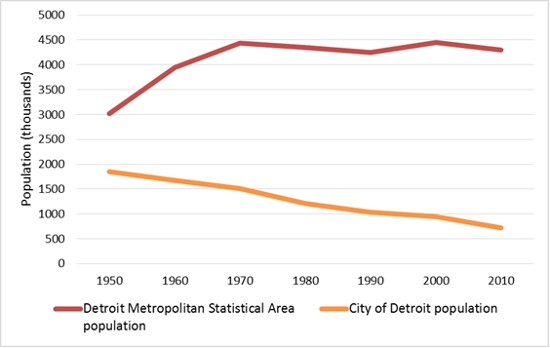

The Detroit metropolitan area had been suffering for decades from the declining fortunes of the American automobile industry, and the central city had experienced massive losses of population, employment, and tax base. However, the disastrous state of the City and its finances did not become fully evident until the last decade. Slow population growth of the metropolitan area produced a loss of population in the central city. As Figure 1 below illustrates, the population of the Detroit metropolitan area reached 4.43 million in 1970, and has varied only slightly since then. The population of the city itself declined from 1.85 million in 1950 to 951,000 in 2000; an average loss of 12.5 percent per decade. In contrast, its population of 714,000 in 2010 is a decline of 25 percent from 2000 (The average population loss for the 17 largest cities of the North was 3.5 percent during the 2000-10). The change in the African-American population of the City from 772,000 to 590,000 accounts for 77 percent of this recent population loss. The population loss means that the city has about 60,000 vacant land parcels and 78,000 vacant structures, of which 38,000 are considered to be dangerous.

Figure 1 – Population of Detroit 1950-2010

Note: MSA in 1950 defined as Wayne, Macomb and Oakland Counties. Monroe and St. Clair Counties are added for 1960, and Lapeer County is added for 1970 and later years.

Total employment in the metropolitan area fell from 2.2 million in 2000 to 1.74 million in 2010, and recovered only to 1.83 million as of 2012. Employment in transportation equipment manufacturing (i.e. autos, etc.) dropped from 180,000 in 2000 to 76,000 in 2010 and came back to 92,000 in 2012. The number of employed residents of the City fell by 39 percent from 2000 to 2010, and median household income in nominal terms dropped from $43,592 1999 to $31,017 in 2009 as many middle-class Detroiters moved to the suburbs. At the same time, the poverty rate jumped from 26 percent to 36 percent.

The housing market in the city of Detroit was devastated. While the metropolitan area did not participate in the housing market bubble that preceded the financial crisis of 2008, the Case-Shiller Home Price Index showed an increase in nominal housing prices of 27 percent for the metropolitan area from 2000 to 2006 (compared to an increase of 126 percent in its ten-city index). From this high point nominal housing prices in metro Detroit fell by 47 percent as of 2011. Median housing prices in the city of Detroit stood at $82,000 in 2007, but this fell to $24,000 when the market collapsed in 2009 and reached bottom at $16,000 in 2011.

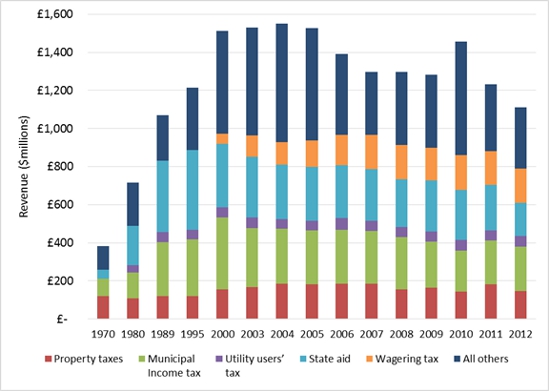

The impact of these forces on the revenues of the City of Detroit is clear. As Figure 2 illustrates, the total revenues for the City of Detroit general fund were $1552 million in 2004 and $1111 in 2012, a real terms decline of 39 percent. With the exception of the wagering tax placed on the city’s casinos, all major sources of revenue fell – property taxes, municipal income tax, state aid, other taxes and federal funds. The wagering tax had been imposed when casinos were approved for Detroit in 1996, and revenue had grown briskly through 2007. However, this revenue source stopped increasing at that point and therefore did not offset the declines in the other funds.

Figure 2 – City of Detroit real general fund revenues 1970 – 2012

The City had been avoiding its fiscal troubles by issuing “Fiscal Stabilization Bonds”, in 2005 ($248 million), 2006 ($35 million), 2008 ($75 million), and 2010 ($250 million). In other words, the City had been borrowing to cover various expenses, including expenditures for current services. Nevertheless, the City had an accumulated deficit of $326 million at the end of fiscal year 2012. Another $137 million in Fiscal Stabilization Bonds was issued in 2013. In addition, the City tried to hide its fiscal problems by failing to make sufficient payments into the pension funds and by deferring maintenance of its facilities.

The Emergency Manager found that, as of June 2012, the total liabilities on the City’s balance sheet were $15.67 billion. Some $5.45 billion of the liabilities are water and sewer bonds, the debt service of which is more than covered by the net revenues of the system, which provides service to many nearby suburbs as well as the city of Detroit. However, the system suffers from lack of maintenance and fails to meet some environmental standards. Most of the remaining liabilities consist of pension obligation certificates ($1.45 billion) and unfunded actuarial accrued liabilities for pensions and other post-employment benefits ($6.37 billion). The accrued liabilities for other post-employment benefits are $5.37 billion, which largely are medical benefits for retirees, which is completely unfunded.

Employees of the City of Detroit had been cut from 18,100 in 1999 to 13,700 in 2009, a decline of 24 percent that is in line with the fall in population. But the payroll did not decline over this period as monthly pay per full-time employee increased by 36 percent. The payroll of the City as a share of the total general fund increased from 50 percent in 1999 to 63 percent in 2009. The decline in city employees meant that benefits paid to retirees increased, so that the police and fire retirement system paid out benefits in 2011 equal to 114 percent of the current payrolls of these departments (up from 79 percent in 2004). The retirement benefits paid from the pension system for other employees were equal to 35 percent in 2004 and 70 percent in 2011 of the payroll of the relevant departments. Payments by the City into the pension systems for fiscal year 2013 were $31 million out of the $134 million that should have been made. The City is unable to provide reliable bus service, prompt fire and police and emergency service, or street lights that work.

As of early 2014 the long-term obligations of the City are estimated at $18 billion. At this time a draft bankruptcy plan calls for the two pension systems to receive about 40 percent of the amount that the City says they are owed, and that about 20 percent of the amount owed to unsecured bond holders would be paid. The formal plan is expected to be filed in federal court in February 2014.

Could the bankruptcy of the City of Detroit have been avoided? Given the steady deterioration of the city from 1950 to 2000 and the events of the succeeding decade, the answer probably is “no.” Avoidance of bankruptcy would have required a different history for Detroit and the American auto industry. Are there other shoes about to drop? Will another major city declare bankruptcy soon? No other major city in the USA has experienced Detroit’s extreme version of urban decline, although many smaller urban areas have lost major employers and are struggling to recover. Cleveland is a central city that has declined greatly over the decades and suffered second-most in the recent decade. But that is a story to be told another time.

This article is based on the paper “What happened to and in Detroit?” in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cUooLf

_________________________________

John F. McDonald – University of Illinois at Chicago

John F. McDonald – University of Illinois at Chicago

John F. McDonald is emeritus professor of Economics and Finance at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Gerald W. Fogelson Distinguished Chair in Real Estate emeritus at Roosevelt University. He received the PhD in Economics from Yale University in 1971, and is the author of eight books that include the text Urban Economics and Real Estate (2nd ed., 2011, with Daniel McMillen) and Urban America: 1950-2030 (forthcoming in 2014). He was elected a Fellow of the Regional Science Association International in 2008, and was awarded the David Ricardo Medal by the American Real Estate Society in 2013.