With extreme weather on the rise across the globe, the way that the media reports climate change and its potential for damage is becoming increasingly important. In Climate Change in the Media: Reporting Risk and Uncertainty, James Painter looks at the way in which newspapers have shifted the way that they report climate change from a language of uncertainty to one of risk. Christopher Shaw finds this book to be a useful summary of climate politics and climate risk, but critiques the lack of discussion on how newspapers’ commercial pressures help to contribute to the wider discourse of excessive consumption, which in turn contributes to climate change.

With extreme weather on the rise across the globe, the way that the media reports climate change and its potential for damage is becoming increasingly important. In Climate Change in the Media: Reporting Risk and Uncertainty, James Painter looks at the way in which newspapers have shifted the way that they report climate change from a language of uncertainty to one of risk. Christopher Shaw finds this book to be a useful summary of climate politics and climate risk, but critiques the lack of discussion on how newspapers’ commercial pressures help to contribute to the wider discourse of excessive consumption, which in turn contributes to climate change.

Climate Change in the Media: Reporting Risk and Uncertainty. James Painter. I.B. Tauris. September 2013.

Climate Change in the Media: Reporting Risk and Uncertainty. James Painter. I.B. Tauris. September 2013.

In Climate Change in the Media: Reporting Risk and Uncertainty, James Painter argues that scientists and politicians are increasingly turning from the language of uncertainty to the language of risk in their descriptions of likely future climate change impacts. This move is presented as a positive development, because uncertainty is a difficult concept to communicate, and prone to being misunderstood or wilfully misinterpreted. Risk language moves the debate on from uncertainty about whether or not industrial activity is driving climate change, to instead focusing on the possible impacts of climate change.

Painter, who is executive editor for the Americas and Europe at the BBC World Service and Head of the Journalism Fellowship Programme at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, analyses the extent to which newspaper reports are reflecting this turn to the language of risk in their reporting of climate change. To do this he examines the reports of three different newspapers from Australia, France, India, Norway, United Kingdom and the USA. He examines the reporting of the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Arctic ice melt. Painter compares what perspectives and assumptions the different newspapers employ in their reporting on these issues using four frames.

The first frame is uncertainty. The second is implicit risk (vague warnings of impending disaster), the third is explicit risk (probabilistic assessments of particular future events occurring). The fourth frame is opportunity, either opportunities arising from a warming world or opportunities arising from the switch to a low carbon energy future. Though the decision to focus his analysis on newspapers in an age of online media may seem difficult to justify, Painter explains that newspapers remain the dominant form in which people encounter the news and the papers chosen for his analysis have a daily circulation of more than 15 million. To his credit Painter is not so wedded to his thesis as to ignore the evidence which casts doubt on the claims that risk language will resonate any more strongly with the public than uncertainty, though he does not extend the scope of his analysis to question what difference the move to a language of risk would make in newspapers whose primary discourse is one designed to promote the consumerist lifestyles driving climate change.

Painter stresses that using the language of risk will be more productive than talking about uncertainty because risk language requires policy-makers to recognise the possibility of catastrophic climate change when deliberating on appropriate mitigation and adaptation strategies, and this framing will resonate with the public because most households are familiar with taking out insurance against low probability high risk events. In the following chapter Painter then examines how frames of uncertainty and risk are currently employed in climate change news reports, citing existing research. He concludes that historically the media have tended to favour stories of disaster from climate change rather than the opportunities to be gained from moving to lower carbon forms of industrial activity.

In the results chapter, each analysis is preceded by a useful summary of each country’s climate politics and the dominant public attitudes within that country towards climate change. The results indicate that newspapers are not yet reporting risk and uncertainty in the way which is increasingly prevalent in policy discourses. Painter concludes that the disaster frame (of implicit risk), which stresses the negative aspects of climate change in its most extreme form, dominates news reports. The uncertainty frame was also identified as a strong theme. These are both considered frames which act to undermine public engagement with the climate change issue. Painter suggests that as modelling of future climate impacts improves so our ability to quantify, and reduce uncertainty, will improve and hence will increasingly come to the fore in policy and science reports. Therefore it is important journalists become more familiar with addressing climate science in terms of probabilities.

The author obviously has a thorough knowledge of the subject and provides a well written and well researched examination of the extent to which newspapers are picking up on and using risk framings. The extensive discussion of results of a content analysis of newspaper framings of uncertainty and risk is certainly to be of appeal to diligent scholars of climate communication, and the book provides a useful summary of the current way climate risk is framed in newspaper reports.

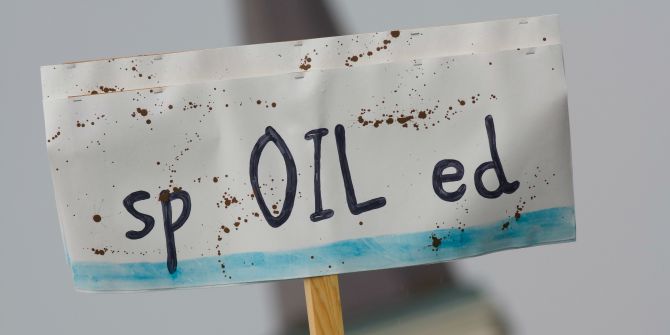

However, there is much about the role of newspaper reporting on climate change which the author fails to address, most notably the commercial pressures on newspapers to make a profit. These commercial pressures mean that newspapers are a part of, and dependent on, the kind of excessive consumption which is driving the year on year record increases in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. It is difficult to appreciate the extent to which a switch from the language of uncertainty to the language of risk can have any effect on public engagement, framed within discourses centred on the instant gratification of needs generated by the advertising which provides the main source of income for the newspapers.

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1eyyvqO

——————————————–

Christopher Shaw – University of Oxford

Christopher Shaw – University of Oxford

Christopher Shaw returned to academia as a mature student and in 2011 was awarded his DPhil by the School of Law, Politics and Sociology at the University of Sussex. He currently works as a Research Assistant for the Climate Crunch project, based at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford. Christopher also works as Research Fellow on the Climate change as a complex social problem programme at the University of Nottingham and is a Visiting Fellow at Science and Technology Policy Research (SPRU), University of Sussex. Read more reviews by Chris.