Common wisdom in international affairs is that when democratically elected leaders and governments make threats towards other states, these are credible; voters will punish leaders who do not follow through on their words. New research by Philip B. K. Potter and Matthew A. Baum argues however, that not all democracies are equal in the credibility of their threats of military action. By analyzing data on international military disputes over a 35-year period, they find that both an effective and widespread media, and a robust opposition are needed in order for voters to become aware of foreign policy blunders. Without either of these, leaders can avoid following through on their threats with little fear of being punished by voters.

Common wisdom in international affairs is that when democratically elected leaders and governments make threats towards other states, these are credible; voters will punish leaders who do not follow through on their words. New research by Philip B. K. Potter and Matthew A. Baum argues however, that not all democracies are equal in the credibility of their threats of military action. By analyzing data on international military disputes over a 35-year period, they find that both an effective and widespread media, and a robust opposition are needed in order for voters to become aware of foreign policy blunders. Without either of these, leaders can avoid following through on their threats with little fear of being punished by voters.

Lately there has been a great deal of debate concerning whether or not democracies are more credible than autocracies when they make demands in the international system. The prior consensus was that democracies are indeed more credible because elections allow leaders to make costly signals that convey credibility. The logic is that potential target states recognize that voters will punish democratic leaders who make public threats and fail to follow through. This makes their signals costly, and hence credible. However, an increasingly prominent revisionist school has challenged this notion, citing both the absence of evidence in the historical record and problems with the data employed to establish the audience cost finding. In our recent research, we challenge a key assumption underpinning this debate: the idea that all democracies are equally credible.

That claim likely seems obvious to policy makers and practitioners. Yet, most of the academic literature assumes that the mere presence of meaningful elections translates neatly into a reliable sanction on a democratic leader’s foreign policy missteps. We argue that the insulation of leaders from the public that is inherent in mass democracy, combined with the established low attentiveness of voters to matters of foreign policy, makes this assumption problematic. In this light, the specifics of the electoral and media institutions that link leaders to voters matters a great deal.

We focused on two institutional features that vary considerably across democracies: the extent of partisan opposition (number of parties in parliament or overall) and media access (TV, Radio). In our view, opposition produces independent political elites capable of whistleblowing, which makes it more likely that that someone will bring to public attention a leader’s foreign policy blunders. The efficacy of whistleblowing, however, is conditional on the public’s access to the mass media as a conduit for communication between leaders and citizens. Absent a robust political opposition, information about foreign policy missteps will be unavailable to the media, and hence to citizens, who will therefore be in a poor position to punish the leader should the policy prove ill conceived. Absent broad public access to the media, the extent and credibility of the opposition matters little, as the public will fail to receive any messages that political elites might send. The implication is that without both robust opposition and widespread media access, democratic leaders are nearly as unconstrained as their autocratic counterparts and by extension have no credibility advantage either.

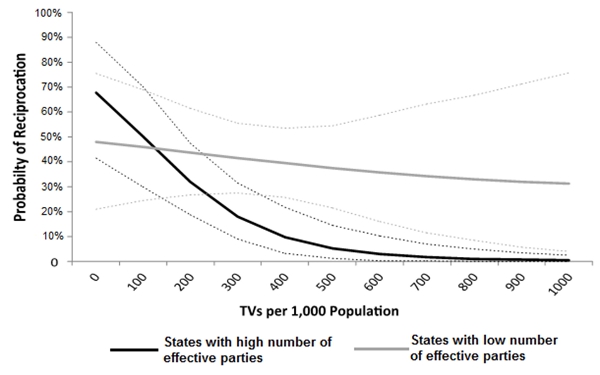

We find support for these arguments in a series of statistical models, using a variety of measures of conflict, partisan opposition, and media access. Our findings are consistent across our specifications, so a single figure suffices to illustrate the core insight. In this iteration of the model we are assessing the rates of “reciprocation” of all initiated militarized disputes from 1965 to 1999. The idea is that states whose threats are more credible will see less reciprocation of the disputes that they initiate (i.e. the other side will concede). We captured the extent of partisan opposition with a measure of the “effective number of parliamentary parties”, and operationalized media access via a count of the number of televisions per 1000 people. In Figure 1 below, the black curve and confidence interval in the figure represents the rate of reciprocation as television access increases for states with a standard deviation above the mean number of parties (“high party” states). The grey line is the equivalent for states with a standard deviation below the mean number of parties (“low party” states).

Figure 1 – Militarized dispute reciprocation, partisan opposition and media access

A few key insights emerge. First, for high party initiators, we find a statistically significant decline in the probability of dispute reciprocation as television access increases. There is no such relationship among low party states. Moreover, there is a statistically significant difference between the reciprocation rates experienced by high- and low-party states at higher levels of TV access, while at lower levels of TV access they are indistinguishable.

The implication is that democratic constraint on foreign policy – and with it credibility – does not arise automatically in democracies and in fact is elusive and fragile. Opposition without effective information transmission through the media will do little to narrow the information gap between elected officials (or agents) and citizens (or principals). Transmission without opposition is no better. One needs both the generation and transmission of information for the system to work.

Viewed in this light, it is unsurprising that a somewhat muddled picture of democratic distinctiveness in the realm of foreign policy emerges from the literature. While there are certainly mechanisms by which democracies can resolve their informational problems and thereby convey credible threats, they are by no means automatic and actually vary a great deal across democracies. The failure to model this heterogeneity (most often by modeling states dichotomously, as either democratic or autocratic) has led to ambiguous findings because leaders who are relatively constrained are lumped together with those who are not.

This article is based on the paper “Looking for Audience Costs in all the Wrong Places: Electoral Institutions, Media Access and Democratic Constraint” in the January 2014 edition of the Journal of Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/LEQm2j

_________________________________

About the authors

Philip B. K. Potter – University of Michigan

Philip B. K. Potter – University of Michigan

Philip Potter is an assistant professor of public policy and political science at the University of Michigan. His ongoing research explores the influence of domestic politics on foreign policy and international relations. He also conducts research in the area of international terrorism and is a principal investigator for a Department of Defense Minerva Initiative project to map and analyze collaborative relationships between terrorist organizations.

Matthew A. Baum – Harvard University

Matthew A. Baum – Harvard University

Matthew Baum is Marvin Kalb Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and Harvard University Department of Government. He is also Faculty Chair of the Harvard Public Diplomacy Collaborative. His research addresses the evolving relationship between the mass media, public opinion and executive decision-making regarding foreign policy.

1 Comments