While the U.S. Senate is now unable to make use of the filibuster to delay judicial nominees to federal circuit and district courts, they must still undergo a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. New research from Logan Dancey, Kjersten R. Nelson and Eve M. Ringsmuth finds that the political environment is a better predictor of the hearing’s content and questions than the characteristics of the nominee under scrutiny. They write that nominees who face confirmation hearings when the presidency and Senate are controlled by different parties are more likely to face questions on crime, abortion, civil rights and on their judicial philosophy.

While the U.S. Senate is now unable to make use of the filibuster to delay judicial nominees to federal circuit and district courts, they must still undergo a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. New research from Logan Dancey, Kjersten R. Nelson and Eve M. Ringsmuth finds that the political environment is a better predictor of the hearing’s content and questions than the characteristics of the nominee under scrutiny. They write that nominees who face confirmation hearings when the presidency and Senate are controlled by different parties are more likely to face questions on crime, abortion, civil rights and on their judicial philosophy.

In November the U.S. Senate invoked the “nuclear option” and ended filibusters on executive branch nominees and nominees to the federal circuit and district courts. Although the change is a significant one, judicial nominees still must face a lengthy process before making it to a final vote. One step in the process is a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, which a former senior counsel in the Office of Legal policy described as, “the variable that injects most uncertainty into the confirmation schedule”. What is the purpose of these hearings? How do senators utilize their opportunity to publicly scrutinize nominees? We set out to answer these questions through an investigation of all U.S. District Court confirmation hearings during the Clinton and George W. Bush presidencies.

Our findings indicate that political and institutional factors (e.g., divided government, the party of the nominating president, and proximity of a presidential election) are better predictors of the types of questions nominees face than are nominee-level factors such as previous judicial experience or the nominee’s rating from the American Bar Association. The results, we argue, indicate that such hearings are typically used more for senatorial position taking than they are for scrutiny of individual nominees. The findings thus raise questions about the value of such hearings.

We analyzed hearing transcripts for the over 500 district court nominees from 1993 to 2008, with the average nominee facing roughly seven questions per hearing. We coded the questions into a variety of categories, including categories related to specific issues (e.g., crime, abortion, civil rights), along with questions about nominees’ judicial philosophy, temperament, background, and ability to manage a docket. The nature of these questions can vary dramatically, from questions like, “Do you believe that racial and ethnic diversity is a compelling government interest in public education?” to “Let me ask you how you were raised and describe the environment you grew up in.” We ultimately wanted to understand why some nominees faced more difficult, ideologically charged questions while others faced what seemed like “softball” (or at least less ideologically charged) questions.

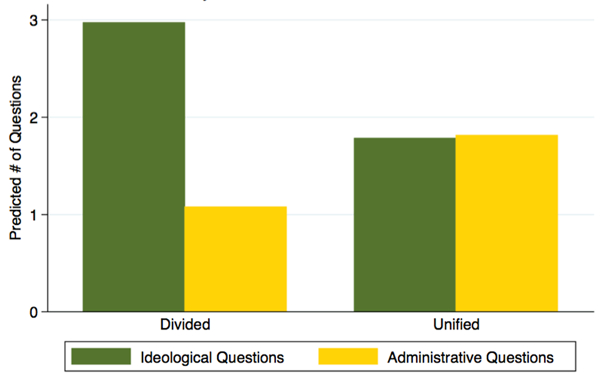

What we found is that divided government (if the presidency and Senate are controlled by separate parties) consistently mattered for the types of questions a nominee faced. Nominees who had confirmation hearings during divided government were more likely to face ideological questions over crime, abortion, civil rights, or judicial philosophy. Divided government meant fewer questions about a nominee’s background or ability to handle a docket. We estimated that divided government increased the number of ideological questions a nominee faced by about one question and decreased the number of docket/background questions by about 0.7. From our observations, these docket and background questions tended to come from the president’s partisan allies and were typically devoid of ideological content.

Figure 1 below shows how the content of hearings changes as we move from unified to divided government. We combined crime, precedent, objectivity, abortion, civil rights, and judicial philosophy into an “ideological questions” category and docket and background into an “administrative questions” category. The predicted number of questions per nominee (from a negative binominal regression model) is presented in the figure. The results show that during divided government, the typical nominee faces about three ideological questions and one administrative question. During unified government, however, the number of ideological questions decreases and the number of administrative questions increases so that the typical nominee faces a roughly even mix of the two types of questions.

Figure 1 – Number of ideological and administrative questions per hearing by divided vs. unified government

Although divided government stood out as having the biggest effect on hearing content, we also saw differences in questions asked based on the proximity of a presidential election. Nominees whose hearings came during a presidential election year were more likely to face questions about their judicial philosophy and less likely to face questions about their ability to handle a court docket.

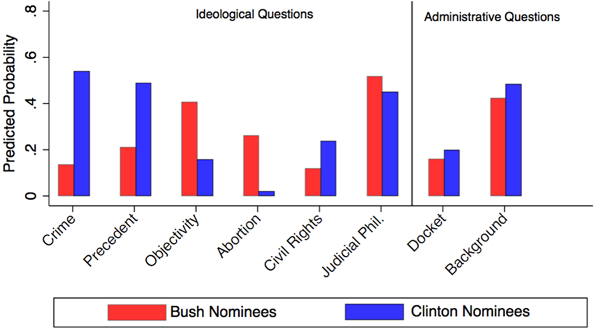

We also observed differences in the types of questions based on the nominating president. Clinton nominees faced significantly more questions about crime, precedent, and civil rights, while Bush nominees faced more questions about abortion and objectivity. Previous research suggests that conservative interest groups often express concern over liberal judges’ positions on race, crime, and judicial “activism,” while liberal interest groups often target conservative nominees on the issue of abortion or whether the judge will treat all groups fairly. Our findings thus conform with what one might expect if senators were using these hearings as an opportunity to appeal to attentive interest groups. Figure 2 below shows the predicted probability a nominee faces certain questions (from logistic regression models) by nominating president.

Figure 2 – Probability nominee gets question in key categories by nominating President

In contrast, individual nominee characteristics had little discernible effect on the types of questions nominees faced during these hearings. We looked at a variety of individual characteristics, from nominees’ race and sex to their previous judicial/prosecutorial experience to different, admittedly indirect, measures of nominees’ ideology. Although individual characteristics mattered in predicting questions in a few of our categories, there was little systematic evidence that nominee-level factors mattered much for the types of questions they received.

What do we make of these findings? On the one hand, it’s encouraging to see that personal characteristics like sex and race of the nominee do not seem to matter for the types of questions senators pose. Our main conclusion, however, is that these hearings are not primarily about vetting individual nominees’ qualifications. The political environment is a better predictor of hearing content than are characteristics of the nominee under scrutiny. Times of heightened political competition (e.g., divided government and presidential election years) lead to more ideologically charged questions. In addition, senators’ questions are often focused on issues known to be of concern to attentive interest groups. The hearings may thus simply be another venue for senators to engage in partisan and ideological position taking.

We are not the first to question the value of Judiciary Committee hearings, with some even calling for the elimination of such hearings for district court nominees We do, however, think our findings add to our understanding of the content of these hearings and can shed new light on the purpose they serve. Committee hearings are one hurdle nominees must jump in a lengthy process to confirmation. Given that the average nominee during the Bush and Clinton years faced a mere seven questions, with the content of the questions varying more based on the political environment than the nominee’s qualifications or background, it is worth continuing to ask whether the information gleaned from the hearings is worth the delay they create.

This article is based on the paper ‘Individual Scrutiny or Politics as Usual? Senatorial Assessment of U.S. District Court Nominees’ in American Politics Research, which is available un-gated from Sage until March 11th.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1kwzwls

_________________________________

Logan Dancey – Wesleyan University

Logan Dancey – Wesleyan University

Logan Dancey is an Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University. His work primarily focuses on the United States Congress and public opinion.

_

_

Kjersten R. Nelson – North Dakota State University

Kjersten R. Nelson – North Dakota State University

Kjersten R. Nelson is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at North Dakota State University. She focuses on the U.S. courts and gender and politics.

_

_

Eve M. Ringsmuth – Oklahoma State University

Eve M. Ringsmuth – Oklahoma State University

Eve M. Ringsmuth is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Oklahoma State University. Her research focuses on the U.S. Supreme Court and the separation of powers.

1 Comments