Robert Dahl, the foremost American political scientist of the post-war era, passed away earlier this month. Bill Kissane looks back at the central role he played in creating the discipline of political science in the United States after the war and his status as the pioneer of democratization studies.

Robert Dahl, the foremost American political scientist of the post-war era, passed away earlier this month. Bill Kissane looks back at the central role he played in creating the discipline of political science in the United States after the war and his status as the pioneer of democratization studies.

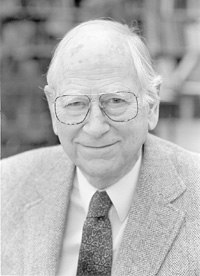

The American political scientist, Robert Dahl, died at the age of 98, at his home on February 10. Dahl was the foremost American political scientist of the post-war era. His academic output includes A Preface to Democratic Theory, Who Governs?, Polyarchy and Democracy and its Critics – all landmarks studies of the nature of modern democracy. Sentiment requires us to speak well of the dead, but few have ever doubted the quality of Dahl’s work. When a straw poll was conducted some years ago in the LSE Department of Government, Dahl was the most popular choice as top political scientist. What explains this degree of consensus?

That his most influential books were published across a span of more than three decades suggests one explanation; his creativity and ambition had a consistent focus. His main ambition was to bring clarity and thoroughness to the question of what type of contemporary government now best lives up to the democratic ideal of a people governing themselves. He argued that the ideal type existed somewhere between the elite-dominated systems people on the left claimed were pseudo-democracy, and systems in which the people actually ruled themselves (genuine democracy). His default concept was polyarchy, a system based on the rule of the many, on the basis that it was broader than oligarchy but more workable than the rule of the people.

That his most influential books were published across a span of more than three decades suggests one explanation; his creativity and ambition had a consistent focus. His main ambition was to bring clarity and thoroughness to the question of what type of contemporary government now best lives up to the democratic ideal of a people governing themselves. He argued that the ideal type existed somewhere between the elite-dominated systems people on the left claimed were pseudo-democracy, and systems in which the people actually ruled themselves (genuine democracy). His default concept was polyarchy, a system based on the rule of the many, on the basis that it was broader than oligarchy but more workable than the rule of the people.

Dahl later explored the contrast between democratic and non-democratic systems in what became a worldwide comparative research project. His basic insight was that what we call democracy was not produced by people becoming democrats. Only structural transformation (for example, the rise of the nation state and the spread of capitalism) could explain this benevolent apparition. Through this research Dahl also indelibly shaped the study of democratisation in two respects. First he tried to identify the necessary institutional characteristics of polyarchy. He came up with eight institutional freedoms which suggested that contestation (rather than just universal citizenship/inclusiveness) was the historically novel quality of polyarchy. Mapping the dimensions of contestation and inclusiveness over time made it possible to trace the progressive institutionalization of civil disobedience across the globe. Secondly, Dahl incorporated the disciplines of comparative history and sociology into the comparative study of democratisation. Yet Dahl was no crude modernisation theorist; he paid careful attention to specific historical trajectories (for example in Switzerland where the lack of a tradition of military involvement in politics was particularly significant to democratic development).

Dahl’s enduring reputation can be explained by three things: (1) the role he played in creating the discipline of political science in the United States after the war; (2) his status as the pioneer of democratization studies and (3) the quality of his mind. Since the first two explanations presuppose the third it is worth stressing that this quality had something to do with the factor he was both political theorist and empirical scholar. Dahl was well aware that economics could reach an analytical sharpness lacking in comparative politics, and his ambitions were empirical. Democracy and its Critics contains philosophical debates between fictional persona in the classical tradition.

The combination of political theory and empirical evidence was also applied to his work on the concept of power. Many believed that modern democracies were no exception to the view that all political systems rest on a division of labour between an active political elite and a largely passive majority. Believing this to be simplistic, Dahl posed three empirical tests for its validity: the elite must be identifiable, organised politically, and its preference must consistently prevail over those of others when challenged. Such was his commitment to the testability and operationalisability of social science concepts that we now have a sharper and more robust language with which to describe modern politics.

Dahl also negotiated the divide between realist and more philosophical approaches to modern democracy well. He rejected realists like the economist Joseph Schumpeter, who defined democracy simply as a method of choosing ruling elites by means of the competitive struggle for the peoples’ vote. In contrast, Dahl argued that while polyarchy was only an approximation of the ideal, it still required genuine commitment to the political ideals of equality, responsiveness, pluralism and self-government. The alternative approach tended to mine the history of political thought for insights as to what democracy could be. Here Dahl’s own realism came to the fore in his brusque critique of the political theories that allegedly underpinned the workings of the American constitution, A Preface to Democratic Theory. Neither Madisonian nor republican theories could explain why the constitution worked. Indeed the sources of limited government were mostly of a sociological rather than legal character and the constitution needed to be seen as part of a political and social, not exclusively legal process.

Another talent was that of turning theoretical puzzles into research agendas. A Preface to Democratic Theory is replete with hypotheses of an empirical kind that moved constitutional thinking away from formal legal analysis, and collapsed the conventional constitutional categories of majority and minority upon which American constitutional doctrines rested. Written a decade before the civil rights movement emerged, his account of the actual role of the Supreme Court in defending people’s freedoms makes for salutary reading. Later on, in his study of decision-making in the city of New Haven, New England, Dahl set himself the task of empirically investigating the question of Who Governs? Contrary to elite theorists, he found that politics was sufficiently unstructured to allow well-organised minorities to present any permanent division of labour emerging.

The combination of theorist and empirical scholar was also suited to his general contribution to democratisation studies. Dahl did not do research abroad; the empirical scholar remained an Americanist. What he did was reflect on the patterns of democratization he saw, consider their origins and consequences theoretically, and leave it to others to carry the subject forward through work on specific regions or cases. Indeed Dahl was the kind of theoretical social scientist that Karl Popper would have approved of. His theories were not based on experiments, or observations. His role rather was to provide very general explanatory frameworks for the patterns of regime change he saw around him. One of the most famous is his observation that high-quality democracies tend to arise when liberalization of a political system precedes the introduction of a mass suffrage. These perspectives loaded the dice against the success of many new democracies.

More recent regime changes have given rise to new debates; whether around the importance of prior regime type for long term-outcomes, the proliferation of hybrid regimes, transitional justice and the role of civil society, the growth of international institutions, or the emphasis placed on actors and their constitutional choices. These have created a rich and varied specialist literature. The study of international politics has become central to democratic change in ways that Dahl did not foresee. Much of the conceptual language is not found in his work. There is unlikely to be a single path to democratisation and the study of variation within regions is probably more fruitful now than the universal theorising in which Dahl specialised. Indeed the best scholars to come after Dahl (Juan Linz, Guillermo O’Donnell, and Adam Przeworski) made general contributions to the field only after working in very specific regional contexts. Nonetheless, in providing a basic theoretical agenda Dahl does deserve the sobriquet ‘the father of democratization studies’.

That later Dahl was more pessimistic about democracy, and perhaps out of sync with the intellectual zeitgeist of the 1990s. After 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the subject of democratisation itself became triumphalistic, with democracy being promoted as an unalloyed public good for every context. The temptation was to see all contexts as pregnant with change: change of the type ‘we’ (i.e. the West) would approve of. Ironically, it was in this period that Dahl himself became skeptical how much democracy one could find in the real world. He had always been aware that polyarchy was both a very new system and one which needed to be reminded of how far it fell short of the traditional ideal. The procedural and ultimately instrumental view of democracy put forward by Schumpter and others has been effectively lampooned by Hilary Putnam who showed how the same logic could easily lead to the totalitarian 1984 depicted by George Orwell. All systems, Putnam argued, needed a moral self-image. Perhaps Dahl sensed that this self-image was being lost. Thus late in his career he became interested in economic democracy, mechanisms of direct democracy, and in root and branch reform of the US constitution.

The early Dahl had made the question of power central to the study of democracy, but deep processes of erosion now extend to the very public power that people are supposed to control. In sensing the hollowing out of democracy, the threat posed to it by large corporations and the media, and the lack of belief in equality today, perhaps the late Dahl, as the Dahl of the 1950s, did have his eye on the future. No doubt the field of democratization studies is no longer the one Dahl was working on. The dynamics of regime change are too various and unpredictable, and Dahl’s early steps have taken people down avenues he could not have foreseen. Nonetheless, Dahl contributed to the establishment of the broad parameters of this field and clearly had the right combination of skills and perseverance to be the pioneer.

Featured image credit: Mike Hiatt (Creative Commons BY NC SA)

Key works by Robert Dahl

A Preface to Democratic Theory, Chicago University Press, 1956

Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an America City, Yale University Press, 1961

Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition, Yale University Press, 1971

Democracy and its Critics, Yale University Press, 1997

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cfDvk7

_________________________________

Bill Kissane – LSE, Government

Bill Kissane – LSE, Government

Bill Kissane is a Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the Government Department of the London School of Economics. His research interests lie broadly within the areas of comparative and Irish politics. He is currently working on two books on civil wars and their aftermaths.

Could you provide a citation for the Hilary Putnam reference (regarding Schumpeter)? I’ve had a difficult time tracking that down, not being familiar with Putnam’s work.

Thanks!