While many speculate that the U.S. could elect its first female president in 2016 with Hillary Clinton, many countries in Latin America already have female leaders at the helm. Jana Morgan examines if these advancements reflect wider support for female leadership or are conditional and subject to change. She finds that male attitudes towards women in politics are susceptible to elite cues and economic conditions, and that support for female leadership is higher among those who are frustrated with the status quo.

While many speculate that the U.S. could elect its first female president in 2016 with Hillary Clinton, many countries in Latin America already have female leaders at the helm. Jana Morgan examines if these advancements reflect wider support for female leadership or are conditional and subject to change. She finds that male attitudes towards women in politics are susceptible to elite cues and economic conditions, and that support for female leadership is higher among those who are frustrated with the status quo.

Over the past decade, women have made significant progress in reaching national-level political office. Female presidents, prime ministers, and cabinet members now set policy in some of the world’s most influential countries and fastest growing economies. Within Latin America and the Caribbean, where women have long been marginalized, five countries currently have female leaders at the helm as president or prime minister (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago), and Chile’s president-elect Michele Bachelet will be returning to office for her second term as president on March 11. Representation for women in national legislatures and cabinet offices has also been on the rise across the region.

In our recent research, Melissa Buice and I explore if these advances in representation for Latin American women are rooted in widespread, deeply held support for female leadership or if attitudes about women in politics are more contingent and thus more prone to reversal.

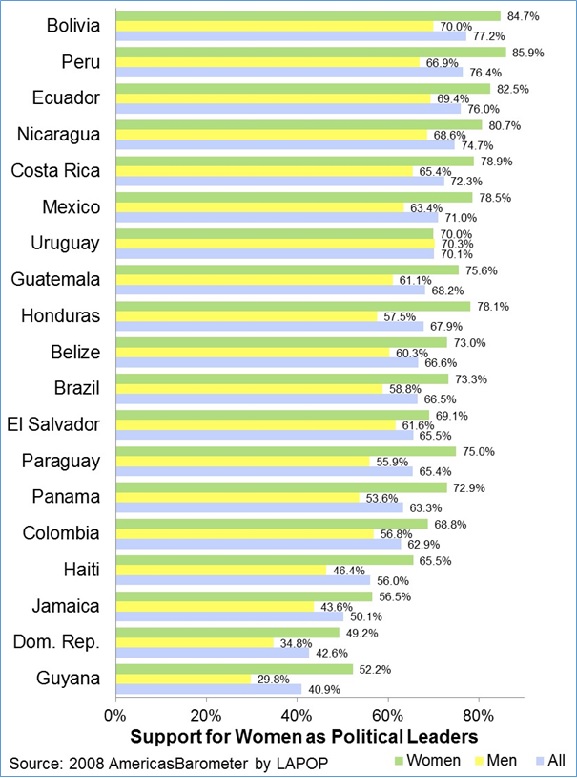

Figure 1: Percent who disagree that men make better political leaders than women, by country and sex

Survey data from AmericasBarometer indicates that support for female political leadership varies considerably across Latin America and the Caribbean (see Figure 1). The Andean countries of Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador express the highest levels of support, while the Caribbean countries of Haiti, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and Guyana lag far behind. In all countries, except Uruguay, women have more egalitarian attitudes than men do.

In analyzing these attitudes toward female political leadership, we found that recent trends toward greater representation for women do not necessarily have their foundation in firm or immutable egalitarian values. Instead, support for female leadership, especially among men, seems to be contingent and potentially vulnerable to reversals.

In particular, male attitudes about women in politics are susceptible to elite cues. In countries where women are nominated to and hold prominent positions in national cabinets, men are more favorable toward female leadership than in contexts where women lack ministerial influence. Thus, male attitudes are dependent upon the decisions made by political elites, and actions that undermine or ignore women’s political credibility have the potential to erode men’s support for female leadership.

Conversely, although we find that opportunities for female professional advancement heighten gender egalitarianism among women with professional jobs who benefit directly from this progress, we do not observe broader, society-wide dividends. Instead, we find that economic opportunities for women produce a backlash effect among men. In countries with more women in professional positions, male support for female political leadership is low. This result suggests that progress toward gender equality is not a self-reinforcing process in which women’s advancement naturally promotes further gains. Rather, men seem to perceive economic progress for women as a threat to their own well-being or advancement, creating a cyclical dynamic in gender egalitarian attitudes instead of promoting steady progress (at least among men).

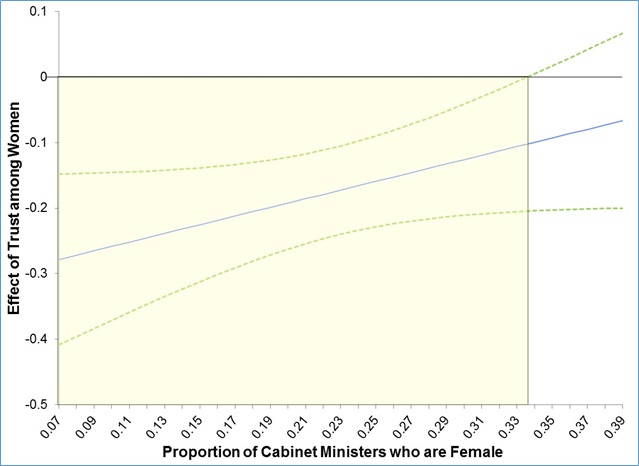

Attitudes regarding political equality for women are contingent in another respect as well. Namely, support for women in leadership is higher among women and men who are frustrated with the status quo. Because female candidates are viewed as outsiders who may disrupt entrenched hierarchies or reform failed institutions, those who are dissatisfied with the current state of affairs are more likely to support the idea of female leadership. However as women make gains in achieving national representation, female politicians lose this outsider status and no longer appeal to those seeking an alternative to the unsatisfactory status quo. Figure 2 shows this conditional relationship for female respondents. We observe the same pattern for males, but men have a slightly lower threshold at which they see female representation as sufficient to weaken their credibility as an anti-establishment option. (The threshold for female respondents is 34%; for men, it is 29%).

When women hold one-third or less of the seats in the cabinet (shaded in yellow), individuals who have less trust in government are more likely to support female leadership. However once women surpass one-third of the seats (unshaded) and are therefore no longer seen as outsiders who might be expected to combat the failings of existing institutions, this relationship disappears.

Figure 2: Effect of trust in government on support for female leadership, conditioned on women’s presence in the cabinet (female respondents)

Thus, our analysis indicates that increasing support for female leadership is not an automatic process that will simply reinforce itself as a result of increased opportunities for women. Economic progress for women is actually associated with less support for female political representation. If elites exclude women from influential and visible positions within the government, public support for gender equality in politics will suffer. And somewhat disturbingly from a normative perspective, strengthening trust in government may actually undermine opportunities for women and other marginalized groups to reach power, because more satisfied citizens are less likely to be drawn to outsiders like women who may represent a challenge to the status quo.

These findings suggest several strategies for policymakers and activists who wish to promote gender equality. First, elite cues matter and politicians should take care that their actions uphold women’s equality. More specifically, female representation in national government has the potential to serve as a catalyst encouraging male support for feminist goals, as having women in leadership generates positive cuing effects (provided their performance in office does not create the perception that they are just part of the failed status quo). Second, access to education and professional employment foster feminist consciousness among the women who benefit from these experiences. Thus, expanding female educational and employment opportunities may provide an avenue for strengthening gender egalitarianism, at least among women.

This article is based on the paper “Latin American Attitudes toward Women in Politics: The Influence of Elite Cues, Female Advancement, and Individual Characteristics” which appeared in the American Political Science Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/MQtgGw

_________________________________

Jana Morgan– University of Tennesse

Jana Morgan– University of Tennesse

Jana Morgan is an Associate Professor of Political Science and the Chair of Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the University of Tennessee. Her research focuses on issues of inequality, exclusion and representation, especially how economic, social and political inequalities affect marginalized groups and undermine democratic institutions and outcomes.