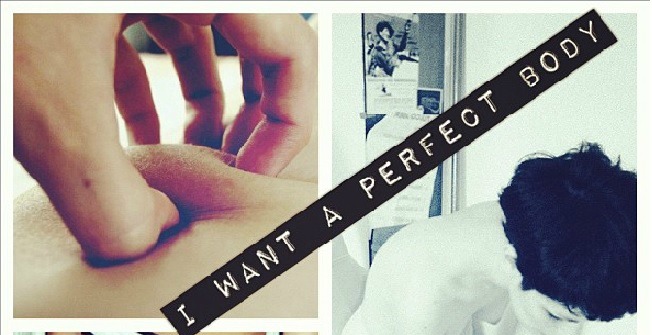

Against the background of the so-called ‘obesity epidemic’, Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection critically examines the discourses of physical perfection that pervade Western societies, aiming to shed new light on the rhetorical forces behind body anxieties and extreme methods of weight loss and beautification. Drawing on interview material with cosmetic surgery patients and offering fresh analyses of various texts from popular culture, this book examines the ways in which the media capitalises on body anxiety by presenting physical perfection as a moral imperative, whilst advertising quick and effective transformation methods to erase physical imperfections. The book’s scope is ambitious and broad, and a range of scholars will find it to be a good starting point for research on bodies, gender and media representations, writes Olivia Monson.

Against the background of the so-called ‘obesity epidemic’, Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection critically examines the discourses of physical perfection that pervade Western societies, aiming to shed new light on the rhetorical forces behind body anxieties and extreme methods of weight loss and beautification. Drawing on interview material with cosmetic surgery patients and offering fresh analyses of various texts from popular culture, this book examines the ways in which the media capitalises on body anxiety by presenting physical perfection as a moral imperative, whilst advertising quick and effective transformation methods to erase physical imperfections. The book’s scope is ambitious and broad, and a range of scholars will find it to be a good starting point for research on bodies, gender and media representations, writes Olivia Monson.

Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection: Cosmetic Surgery, Weight Loss and Beauty in Popular Culture. Deborah Harris-Moore. Ashgate. January 2014.

Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection: Cosmetic Surgery, Weight Loss and Beauty in Popular Culture. Deborah Harris-Moore. Ashgate. January 2014.

“Have you ever considered a chin implant?” An innocuously delivered question from a plastic surgeon proves to be the catalyst for Deborah Harris-Moore’s first book Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection. Harris-Moore, a faculty member of the Writing Program at the University of California Santa Barbara, takes the reader on a wide-ranging journey as she constructs her argument for the connection between cosmetic surgery and weight loss as part of an overarching rhetoric of perfection perpetuated by Western media.

What makes this work a unique contribution to a topic on which there is already a great deal of research in other disciplines is the compelling personal story in Part II of the Preface. During adolescence Harris-Moore experienced anorexia and bulimia that led to hospitalization. Then as a graduate student in her mid-twenties ‘corrective surgery’ to straighten her nose after orthodontic surgery resulted in her getting an implant in her chin, “one of the only body parts I had never critiqued or even noticed before my first consultation”. She intuitively feels that her focus on weight control and the various procedures (such as chemical peels and vein removal) which culminate in the chin implant arise from the same obsession with physical perfection. The implant led her to question her own role in her decisions and obsession or whether there was “something larger” at work. Understanding this history and motivation is essential in understanding Harris-Moore’s approach and response to both the previous research and theory, and the data she examines; “my own experience serves as the lens through which I read these texts”. We get a sense of a struggle to come to terms with the influences of the media and the medical profession without surrendering individual agency.

The book is broken into 6 chapters, the first providing context by detailing the historical constructions of fatness and the development of surgical transformation. Harris-Moore then examines and pulls apart the rhetoric of an extensive range of cultural sites including Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign, a People magazine article about plastic surgery for “real people”, reality television programs including The Swan and The Biggest Loser, and films and television programs including Shallow Hal and How I Met Your Mother. Harris-Moore also analyses interview data collected from individuals who have undergone some type of physical transformation. The final chapter looks to the future by examining how resistance to the dominant discourse is enacted in documentary films. Along the way Harris-Moore addresses issues of agency, class, race, and gender.

The chapter “Reality Television Transformations” examines the “allure” of transformation by comparing plastic surgery programs, The Swan in particular, with the dominant weight-loss program The Biggest Loser. Although The Biggest Loser has been reproduced in many countries, The Swan may be less familiar to non-American readers and this section may not resonate with those who haven’t seen the program or been part of the cultural landscape in which it is played out (YouTube clips here). However, Harris-Moore captures the ubiquitous nature of weight-loss rhetoric and connects surgical and weight-loss transformations to the importance of the body as a cultural symbol of character and moral value. The analysis of The Biggest Loser at times perpetuates the discourse it is critiquing, in particular the notion that a fat body is problematic and that the ‘cause’ is emotional. And the discussion of gender fails to make the important point that the gender differences and stereotypes that are evident in The Biggest Loser are constructed through editing choices rather than being ‘real’.

The chapter “Gaining and Losing in Real-life Transformations” attempts to explicate the experiences of others who have undergone a range of transformative procedures from liposuction and gastric bypass surgery to a prosthetic testicle and tattooing. Harris-Moore’s intention is to uncover the driving forces behind the decision to modify one’s own body, and thus allow for a new, more positive, narrative of body transformation informed by actual experiences rather than theory or popular perception. Harris-Moore seems to have approached this data with a set of expectations which have informed the analysis, and as a result the analysis is problematic at times and seems to go beyond what is in the data extracts provided. This chapter would have been stronger without the inclusion of the tattooed participant; although the process may be considered a transformation it doesn’t sit comfortably within beauty rhetoric and thus detracts from the main premise of the book. Despite this, the personal stories are fascinating and they certainly highlight the complex emotional experiences behind body transformations.

The scope is ambitious and broad to the point that many discussions leave the reader wanting more. For example, the differences between Extreme Makeover and The Swan, both in structure and audience response and reception, is intriguing and could have warranted a chapter of its own. As a positive, however, due to the wide range of data and cultural texts discussed, an equally wide range of scholars will find this book to be a good starting point for their research.

What is particularly interesting about this book is that it represents a point in time in which the critical approach to weight loss and beauty discourse is being applied beyond the disciplines in which it is predominantly employed (critical health psychology and fat studies, for example). Additionally, it represents a personal awakening of that critical eye that is empowering to the author.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1tNzGrL

_________________________________________

Olivia Monson is a 3rd year PhD candidate in the School of Psychology and Exercise Science at Murdoch University in Western Australia. Her research focuses on obesity and weight loss discourse and how they are enacted across a variety of popular sites including The Biggest Loser and government health campaigns. She is more broadly interested in Critical Health Psychology and Qualitative Methods.

Olivia Monson is a 3rd year PhD candidate in the School of Psychology and Exercise Science at Murdoch University in Western Australia. Her research focuses on obesity and weight loss discourse and how they are enacted across a variety of popular sites including The Biggest Loser and government health campaigns. She is more broadly interested in Critical Health Psychology and Qualitative Methods.