The Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate has been one of the most hotly debated segments of the already controversial law, but it is by no means the first time the federal government has become involved in family planning. Johannes Norling, Martha J. Bailey, and Olga Malkova examine how federally funded family planning programs begun in the 1960s and 1970s affected childhood and adult poverty rates. They find that parents’ access to affordable contraception is associated with lower poverty rates for their offspring, both during childhood and later in life.

The Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate has been one of the most hotly debated segments of the already controversial law, but it is by no means the first time the federal government has become involved in family planning. Johannes Norling, Martha J. Bailey, and Olga Malkova examine how federally funded family planning programs begun in the 1960s and 1970s affected childhood and adult poverty rates. They find that parents’ access to affordable contraception is associated with lower poverty rates for their offspring, both during childhood and later in life.

Approximately one in five U.S. children lives below the official poverty line. Nearly half of children born into the poorest fifth of families remain very poor as adults. The persistence of child poverty and its potentially negative consequences for children’s opportunities has made reducing child poverty a public policy concern.

In our recent research, we demonstrate that parents’ access to affordable contraception is associated with lower poverty rates for their offspring in childhood and in adulthood. Our results suggest that 79,800 fewer children and 46,760 fewer adults were living in poverty as a consequence of family planning grants. This implies a cost approximately $32,581 per child reduction in the poverty rate, and about $55,603 per adult reduction in poverty rates. These calculations likely overestimate costs of reducing poverty rates due to family planning, because they do not measure the benefits to children born just before funding—children who may have benefited due to changes in household composition and age structure.

Brief History

In 1960, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral contraceptive. “The Pill,” as it would become known, offered a safe, reliable and female controlled contraception and immediately became popular. But its cost proved a barrier to use for low income women. Beginning under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, from 1964 through 1973, the federal government funded more than six hundred family planning programs across the U.S. These programs provided family planning counseling and contraceptives (but not abortion services) at highly subsidized prices and served four million poor women per year by 1983.

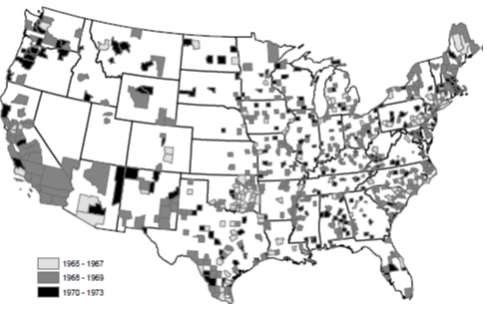

The introduction of family planning programs varied geographically and across time (figure 1). In more than half of states, programs were established in at least five different years. Access to affordable contraception encouraged women to use more reliable methods and reduce childbearing. Fertility rates dropped by 1.4 to 2 percent in counties after they received these programs and remained lower for at least fifteen years.

Figure 1: Dates of the first federal family planning grant by US county, 1965-1973

Source: National Archives: Records about Community Action Program Grants and Grantees, Federal Outlays System Files; Office of Economic Opportunity: Need for Subsidized Family Planning Services: United States, Each State and County, 1968, 1969, and 1971.

The Link between Family Planning and Poverty Rates

There are several channels through which family planning programs may affect poverty rates. First, standard quantity-quality formulations of the demand for children suggest that fewer children in the household may encourage parents to spend more time and money on each.

Second, parents may increase their resources directly as a consequence of family planning programs. Delaying childbearing may help parents gain more education, work experience and job training, and, thus, increase their lifetime earnings. A standard quantity-quality formulation of the demand for children suggests that higher income will encourage investments in children.

Third, the most disadvantaged parents may have benefitted most, because higher income households would have received family planning services from private providers in the absence of subsidies. Reductions in childbearing to lower income households would also tend to raise the resources of the average child. Standard quantity-quality formulations, again, suggest that more household resources should be associated with higher investments in children, so the average child born after family planning programs began would tend to receive more investments than those born before.

Empirical Tests

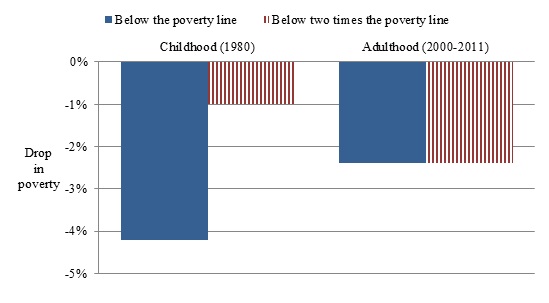

We use the 1980 census to examine these predictions empirically. Our research design compares cohorts of children born in the two years before a program was funded to cohorts born in the same county group up to six years afterwards. Our results show that children born after funding began were 4.2 percent less likely to live in poverty in 1980. Consistent with effects being larger at lower income thresholds, the reduction in the share of children living below 2 times the poverty line was a smaller 1.0 percent (figure 2).

We next use the 2000 census and 2005-2011 American Community Survey to examine whether reductions in poverty were persistent. Using the same research design, we find that cohorts born just after the programs were funded were 2.4 percent less likely to live in poverty as adults 30 to 40 years later—an estimate that is identical for 2 times the poverty line (figure 2).

Figure 2: Drop in poverty rates for cohorts born after family planning funding began

Source: 1980 and 2000 US Census; 2005-2011 American Community Survey

Source: 1980 and 2000 US Census; 2005-2011 American Community Survey

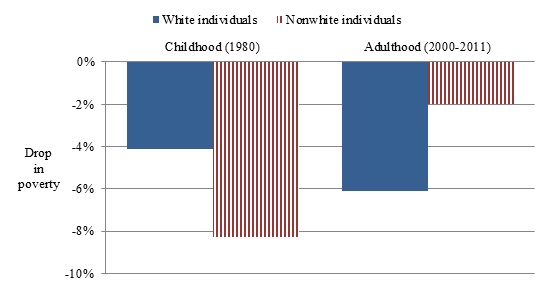

The effects of family planning programs also differed by race (figure 3). This disparity could reflect both differences in the demand for contraception as well as differences in household resources across groups. In childhood, whites experienced a 4.1 percent drop in poverty while non-whites experienced an 8.3 percent drop in poverty. In adulthood, the drop in poverty was 6.1 percent for whites and 2.0 percent for non-whites.

Figure 3: Drop in poverty rates after funding of family planning began, by poverty level

Source: 1980 and 2000 US Census; 2005-2011 American Community Survey

This article is based on the paper “Do Family Planning Programs Decrease Poverty? Evidence from Public Census Data,” which appeared in CESifo Economic Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1fyBtwZ

_________________________________________

Johannes Norling- University of Michigan

Johannes Norling- University of Michigan

Johannes Norling is a Ph.D. candidate in the Economics Department and a trainee at the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan. He studies economic development, history, and demography, and his dissertation research focuses on sex preferences during childbearing and the relationship between contraception and fertility.

Martha J. Bailey- University of Michigan

Martha J. Bailey- University of Michigan

Martha J. Bailey is an Associate Professor of Economics and a Research Associate Professor at the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan. She is also a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Her research focuses on issues in labor economics, demography and health in the United States, within the long-run perspective of economic history.

Olga Malkova- University of Michigan

Olga Malkova- University of Michigan

Olga Malkova is a Ph.D candidate in the Economics Department and a trainee at the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan. Her research focuses on issues in labor economics, health economics and demography in the United States and Russia. Her dissertation examines the effect of family policies on fertility and children’s outcomes.