Americans are taxed at a federal – and often state – level. But what affects whether or not states adopt taxes? In new research, Thomas Hayes and Christopher Dennis have determined that the concentration of wealth matters for state tax systems. They find that there is a positive relationship between income going to the top 1 percent and the likelihood a state will adopt an income tax, suggesting that state authorities are keen to capture the income of top earners when income becomes highly concentrated. They also find that the higher the concentration of income in a state, the more likely the state is to allow taxpayers to deduct federal income taxes from state taxes.

Americans are taxed at a federal – and often state – level. But what affects whether or not states adopt taxes? In new research, Thomas Hayes and Christopher Dennis have determined that the concentration of wealth matters for state tax systems. They find that there is a positive relationship between income going to the top 1 percent and the likelihood a state will adopt an income tax, suggesting that state authorities are keen to capture the income of top earners when income becomes highly concentrated. They also find that the higher the concentration of income in a state, the more likely the state is to allow taxpayers to deduct federal income taxes from state taxes.

The progressivity of a state’s tax system can substantially affect income inequality within a state. An individual state’s decision to adopt an income tax, for example, can have profound implications on the distribution of income within a state as well as the social safety net available to poor citizens. In recent research, we examined the ways in which the concentration of income within a given state can affect state tax policy decisions (e.g. whether to adopt an income tax or whether to permit the deduction of federal income taxes against state income taxes). We find that there is a positive relationship between income going to the top 1 percent and the likelihood a state will adopt an income tax and permit deductions of federal taxes against state taxes.

Another key aspect of state tax policy that we examined is whether or not a state permits deducting federal income taxes against state individual income taxes. States in which income taxpayers are permitted to deduct their federal income taxes from their state individual income taxes raise less revenue than if federal income taxes are not deducted. Furthermore, since the federal income tax is progressive, permitting state income tax payers to deduct federal income taxes against their state individual income tax liability will disproportionately benefit upper-income individuals and will make a state’s individual income tax less progressive.

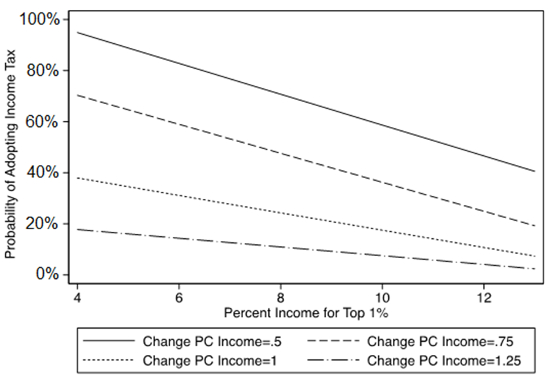

We examined the extent to which massive concentrations of wealth affect state tax policy by re-examining the adoption of state individual income taxes between 1916 and1937, which was previously analyzed by Berry and Berry (1992). In replicating and updating this previous paper, we find that the concentration of wealth matters for state tax policy, and that there is a positive relationship between income going to the top 1 percent and the likelihood a state will adopt an income tax. We find that states are more likely to adopt an income tax when there are higher percentages of income flowing to the top 1 percent, suggesting that states have a desire to capture the income of top earners when income becomes highly concentrated. Most interesting however, is that an interaction between Change in Per Capita Income and the percentage income going to the Top 1 percent demonstrates support for the idea that the wealthy are able to resist efforts of taxation when the economy is struggling. This phenomenon is seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Predicted Margins of Interaction Effect (Change in per capita income X Top 1 percent)

Figure 1 displays the probability a state will adopt an income tax (y-axis) for different values of the change in Per Capita Income, plotted against the Top 1 percent variable on the x-axis. The figure shows that the probability of a state adopting an income tax is highest when the economy is struggling (e.g. low values of Per Capita Income). However, this likelihood of adopting an income tax decreases as income becomes more concentrated.

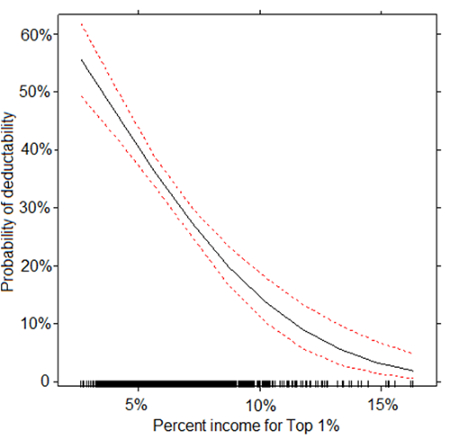

Similarly, we examined deductibility of federal income taxes against state individual income taxes. This is an issue that significantly affects both the amount of money a state raises through its income tax and the distribution of the tax burden. Figure 2 shows that the percent of income for the top 1 percent in each state has quite a large impact on whether deductibility is permitted. This figure contains a solid line, which indicates the predicted values of the percentage of income going to the top 1 percent with the dotted lines indicating confidence intervals for the predicted values. The tick marks along the x-axis show the distribution of the variable measuring the percentage of income going to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers. The figure shows a clear negative relationship between the share of income for the wealthy and the likelihood a state will allow taxpayers to deduct federal income taxes from their state taxes.

Figure 2- Probability of Deductibility by Percent Income Going to Top 1 percent, 1960-2003

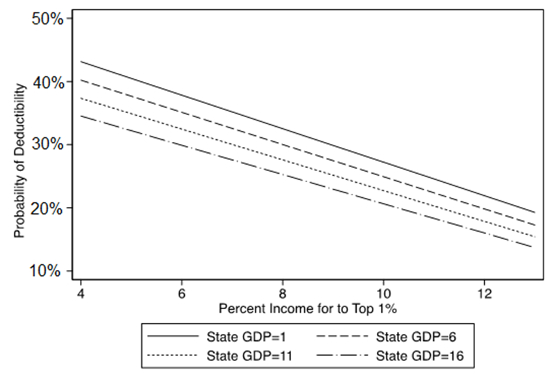

We also examine the interactive effect between GDP and the concentration of income within a state. We find that states are no more likely to permit deductions when the economy is doing well. However, the efforts of states to continue to capture revenue (by resisting efforts of allowing deductions) become less likely as income becomes more concentrated. This phenomenon can be seen in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – Predicted Margins of Interaction Effect (GDP*Top 1 percent).

In the context of the degree to which the percentage of income going to a wealthy population influences state tax policy we tested whether or not a state should have an individual income tax, and if a state does have an individual income tax, should it permit taxpayers to deduct federal income taxes against state individual income taxes? Both of these questions materially affect both the size and distribution of a state’s tax burden as well as the ability of states to combat the negative effects of wealth inequality.

The impact of the share of income going to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers provides interesting results. In each of the models tested, whether for the adoption of state income taxes or for the deductibility issue, the percentage of income going to the top 1 percent was statistically and substantively significant. Rather than demonstrating that this flow of income to the wealthiest led to increased power among this group (at least in terms of resisting the implementation of an income tax), states were more likely to adopt an income tax when the percentage of income going to this group was large.

Similarly, the share of income going to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers was a significant predictor in every model of the willingness of states to permit deducting federal income taxes against state individual income taxes. The relationship was always negative. The greater the share of income going to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers, the less likely a state was to permit deducting federal income taxes against state individual income taxes. As with the adoption of a state individual income tax, the results support a desire of states to retain revenue from wealthy individuals.

The interactive effect between state growth and the concentration of income demonstrated important findings as well. Low growth states were more likely to adopt an income tax, yet this likelihood decreased as the percent flowing to the Top 1 percent increased. Similarly, states were more likely to permit deductions when economic growth is sluggish, but the probability of adopting decreases as the percent income flowing to the Top 1 percent increases. To the extent to which the wealthy oppose an income tax or desire deductions of federal taxes against state income taxes, their power seems to wane somewhat during bad economic times. That power, however, seems to increase as the concentration of income increases. Therefore, it seems that while states have a desire to use the political opportunity of sluggish economic growth (which might fuel resentment against the wealthy), the likelihood of either adopting an income tax or resisting efforts to permit deductions decreases under circumstances in which income is highly concentrated.

Our results both support and extend the important work of Berry and Berry (1992), which find state tax policy depends upon the political opportunity for state politicians to receive cover to implement a tax. Our results indicate that large shares of income going to the top 1 percent may contribute to that cover, as states seem to want to capture some of the wealth flowing to the wealthiest. While the wealthy may have disproportionate influence on the political system, it seems that this influence is not absolute—states still need to take in revenue and the wealthiest citizens are prime targets as income concentrations grow.

Our results show that the share of income received by the richest 1 percent of taxpayers does have an impact on the likelihood states will adopt an income tax and permit deductions of federal taxes against state taxes. As the top 1 percent has seen most of the benefits of increasing inequality, our findings suggest that future studies should continue to take into account the degree to which the wealthy have significant influence on policy as well as the degree to which states are able to respond to this growing concentration of wealth.

Finally, as researchers continue to examine the causes and consequences of growing wealth inequality in the United States, our findings suggest scholarship should examine the degree to which partisan differences in policy matter not just at the national level, but also at the sub-national level. Individual states are often the key governmental actor for citizens in many areas of social welfare policy, as welfare is largely run through the states. Therefore, future research must focus on the ways in which state governments, and the tax policies they adopt, respond to growing wealth inequality.

This article is based on the paper ‘State Adoption of Tax Policy: New Data and New Insights’ in American Politics Research, which is available ungated thanks to Sage until August 15th.

Featured image credit: 401(K) 2012, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1tRRN2m

_________________________________

Thomas J. Hayes – University of Connecticut

Thomas J. Hayes – University of Connecticut

Thomas J. Hayes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Connecticut. Professor Hayes specializes in the fields of American politics and political behavior, with an emphasis on economic inequality.

_

Christopher Dennis – California State University, Long Beach

Christopher Dennis – California State University, Long Beach

Christopher Dennis is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at California State University, Long Beach. Dr. Dennis specializes in American politics, with particular emphasis on the role of political parties and state politics.

Your article seems to imply that Fedral Taxes are deducted the State Tax Return.

While this may occur in some States I am not familar with.

Howerver, until the last 4 years, State Income taxes paid could be deducted on the Federal Tax Return.

Now it is very limited, because it seems the Red States want the Blue States to pay more Federal Income

Taxes.

Most Red States recieve more mony from the Federal Goverment Spending programs than they pay the

Federal Government in Federal Income Taxes. By eliminating or significantly reducting State and Local Tax

decutions on the Fedral Tax Return there is more money to send to the Red States.