How has economic liberty changed in the developed world over the past two centuries? Leandro Prados de la Escosura presents findings from an analysis of the historical development of economic freedoms in OECD countries since 1850. He illustrates that economic liberty rose steadily from 1850 until the outbreak of the First World War, before experiencing a sharp decline in the mid-20th century. However since the end of the Second World War, economic freedom has risen to a point where it now sits at its highest level in modern history.

How has economic liberty changed in the developed world over the past two centuries? Leandro Prados de la Escosura presents findings from an analysis of the historical development of economic freedoms in OECD countries since 1850. He illustrates that economic liberty rose steadily from 1850 until the outbreak of the First World War, before experiencing a sharp decline in the mid-20th century. However since the end of the Second World War, economic freedom has risen to a point where it now sits at its highest level in modern history.

How has freedom evolved over time? A distinction has been made between ‘negative’ freedom, defined as lack of interference or coercion by others (freedom from), and ‘positive’ freedom, that is, the guarantee of access to markets that allow people to control their own existence (freedom to). An example of negative freedom is economic liberty. A country will be economically free in so far as privately owned property is securely protected, contracts enforced, prices stable, barriers to trade small, and resources mainly allocated through the market.

A tension has long existed between the view that perceives the extension of freedom as the most effective way to promote welfare and equality, and the view that stresses welfare and equality as prerequisites of freedom. It has been argued that every society faces a trade-off between preserving individuals’ innate (negative) freedom to enhance their wellbeing, and constraining this innate freedom so individuals, by enhancing their positive freedom, achieve wellbeing. Does this trade-off apply in the long run? My research investigates whether such a trade-off holds over time, or just during specific periods. In order to do so, I need to construct measures of negative and positive freedoms. Since a proxy for positive freedom, namely, a new historical index of human development, is already available, I am currently focusing on negative freedom.

A new Historical Index of Economic Liberty (HIEL) provides a long-run view of economic freedom and its main dimensions for today’s advanced nations, more specifically, those included in the OECD prior to its enlargement since 1994. Given the bounded nature of any index of economic freedom, the use of its percentage change or rate of growth would be misleading as increases achieved at low levels cannot be matched at high levels. It is preferable, then, to look at the absolute shortfall of economic freedom from its upper bound at the initial point and, then, compute its relative decline over a given period. Thus, the improvement is measured as the proportion of the maximum possible (that is, the reduction in its shortfall).

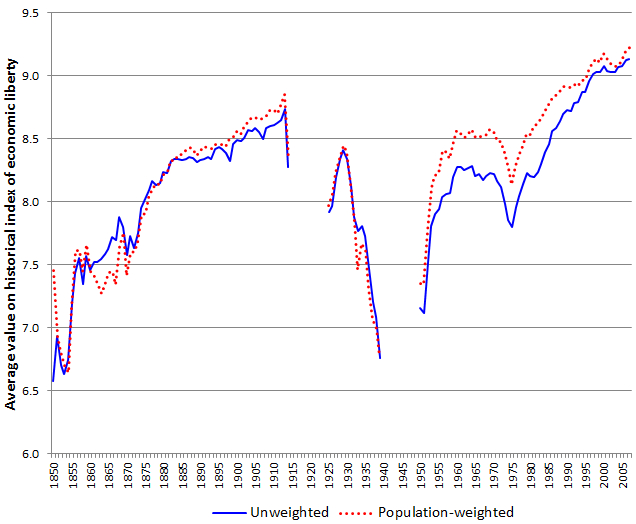

As Figure 1 shows, economic liberty is higher nowadays in the OECD than at any time over the last one and a half centuries and, probably, in history. Over 1850-2007, the shortfall declined by nearly three-quarters. However, its evolution has been far from linear. Different phases can be established.

Figure 1: Evolution of economic freedom (historical index of economic liberty values) in OECD countries between 1850 and 2007

Note: The figure shows the average value for OECD countries on the author’s historical index of economic liberty between 1850 and 2007. The higher the value on the vertical axis, the higher economic liberty was on average in OECD countries.

From the mid-nineteenth century to the eve of World War I steady advancement of economic liberty took place across the board, peaking in 1913, although it is up to the early 1880s when most of the action happened. Over three-quarters of the overall progress in economic liberty in the OECD up to 2007 had been achieved before World War I.

During the first half of the twentieth century economic freedom suffered a severe reversal. After a dramatic decline during the war and its aftermath, the recovery was fast and peaked by 1929, but at the level of the late 1890s. The Great Depression pushed down economic freedom again and the post-Depression recovery did not imply a rebound of economic liberty so, by the eve of World War II, it had shrunk to the level of the early 1850s.

Economic freedom expanded in the second half of the twentieth century and peaked by 2007. However, in between two expansionary phases: a quick recovery in the 1950s and a post-1980 expansion, economic freedom came to a halt, stabilising during the 1960s around the late 1920s level, and declining in the early 1970s. From the early 1980s to the eve of the current recession, a sustained expansion took place, overcoming the 1913 peak after 1989 and reducing the early 1980s shortfall to half by the mid-2000s. In the last two decades the highest levels of economic freedom have been reached.

Over time improvements in economic liberty derived from different dimensions. Thus, between 1850 and 1914, the improvement in property rights made the main contribution. Then, during the first half of the twentieth century, it was the collapse of freedom to trade internationally that was chiefly responsible for the contraction in economic liberty. Since the mid-20th century, specifically in the 1950s and the post-1980 era, the liberalisation of trade and factor flows was the leading force, accounting for more than half of the reduction in the economic freedom shortfall over 1950-2007. During the 1960s and 1970s, increases in regulation and unsound monetary policies offset the gains in freedom to trade and improvements in property rights. Overall, improvements in the legal structure and property rights emerge as the main force behind long-term gains in economic liberty during the last one and a half centuries.

The trends exhibited by the new historical index of economic liberty raise pressing questions. If economic freedom is usually associated with economic growth, how can we reconcile good economic performance in the OECD during the 1960s and early 1970s with stagnant and relatively low levels of economic freedom? Furthermore, are there any trade-offs between economic liberty, as a negative freedom, and other kinds of positive freedom, in particular, human development and democracy? Answering these questions provides an exciting research agenda which is well worth pursuing.

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Credit: Tracey O (CC BY SA 2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1rn2hmI

_________________________________

Leandro Prados de la Escosura – Universidad Carlos III, Madrid / CEPR / LSE

Leandro Prados de la Escosura – Universidad Carlos III, Madrid / CEPR / LSE

Leandro Prados-de-la-Escosura, D. Phil. (Oxford) and Ph.D. (Complutense, Madrid) is Professor of Economic History at Universidad Carlos III, Madrid. He is also a Research Fellow at the CEPR, a Research Associate at CAGE, and Corresponding Fellow of Spain’s Royal Academy of History. During 2013-14 has been Leverhulme Visiting Professor at the LSE.