The evolution of historically poor, but creative, neighborhoods into affluent gentrification is a common trend in many large cities in the U.S. and the West. In new research, Jenny Schuetz examines the role that art galleries play in this trend toward gentrification. She finds that while galleries tend to choose neighborhoods with affluent college educated households, they are not themselves a cause of gentrification, and are not the source of further neighborhood transition after they are established.

The evolution of historically poor, but creative, neighborhoods into affluent gentrification is a common trend in many large cities in the U.S. and the West. In new research, Jenny Schuetz examines the role that art galleries play in this trend toward gentrification. She finds that while galleries tend to choose neighborhoods with affluent college educated households, they are not themselves a cause of gentrification, and are not the source of further neighborhood transition after they are established.

Mimi and Rodolfo of La bohème would have difficulty finding a picturesquely dilapidated garret in today’s cleaned-up Latin Quarter – and even more difficulty affording the rent. Other well-known examples of gentrified Bohemia include London’s Bloomsbury and Hackney districts, Berlin’s Kreuzberg, and New York City’s SoHo and Chelsea neighborhoods. These once-shabby, low-rent enclaves became known for their concentrations of artists, writers, and musicians – not to mention their favorite watering holes – then gradually attracted more affluent residents and mainstream commercial activity.

Many historically artsy neighborhoods evolved organically into affluence. More recently, local economic development policies offer subsidies, preferential zoning, or other incentives to artists, galleries, performance venues, or the “creative class” more generally. One popular strategy is to encourage the reuse of abandoned warehouses and similar industrial spaces as art galleries. Galleries, especially “star” galleries owned by well-known dealers, have the potential to draw culturally-oriented visitors to a neighborhood, which in turn may attract new residents, shops and restaurants. Despite case studies of neighborhoods like SoHo, the causal relationship between art galleries and gentrification has not been rigorously established. Do galleries cause neighborhoods to transform, or are they drawn to neighborhoods with higher propensities to gentrify?

New evidence finds that in New York City, galleries choose high-amenity neighborhoods, but do not independently cause those neighborhoods to transform. To examine whether galleries lead to neighborhood redevelopment, I assembled an inventory of art galleries operating in Manhattan from 1970 through 2003. During the study period, roughly 800-1000 galleries per year operated in Manhattan, more than twice as many as in any other U.S. city. The study first examines whether galleries seek out locations with particular economic and physical amenities, and then analyzes whether gallery neighborhoods undergo more physical redevelopment, conditional on initial amenities.

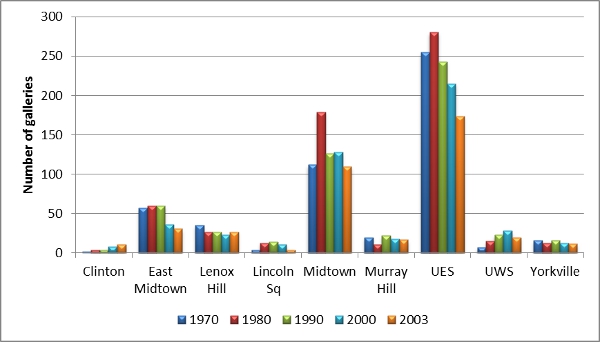

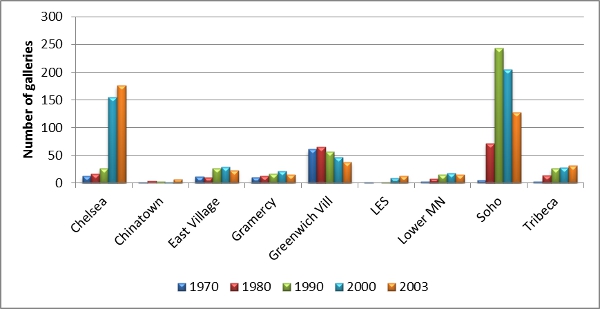

Like antique dealers and high-end furniture stores, galleries are highly spatially concentrated in a few neighborhoods (Figures 1-2). Roughly 70 percent of all Manhattan galleries are located in just four neighborhoods: Chelsea, Midtown, SoHo and the Upper East Side. These clusters are remarkably persistent over time — Midtown and the Upper East Side have been gallery destinations since the 1940s, SoHo since the mid-1970s — despite the relatively short life-span of most individual galleries.

Figure 1 – Galleries in Uptown neighborhoods, 1970-2003

Source: Manhattan Gallery Database

Figure 2 – Galleries in Downtown neighborhoods, 1970-2003

Source: Manhattan Gallery Database

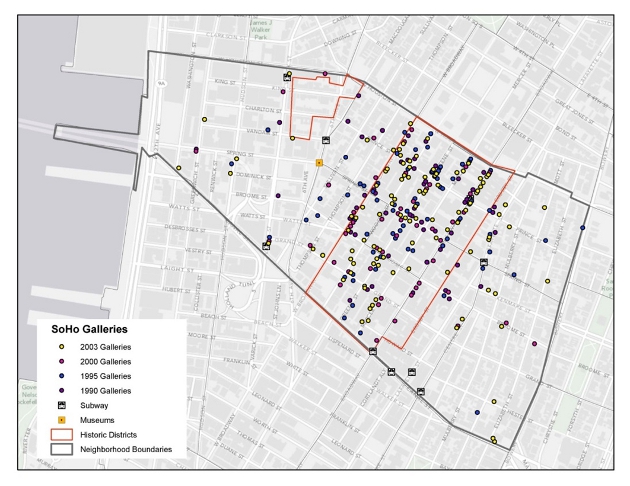

Some of the persistence is due to agglomeration economies: new galleries benefit from opening near existing galleries, especially “stars” that attract high-volume (and high net-worth) visitors to the neighborhood. Galleries also prefer neighborhoods with place-specific amenities, such as high quality architecture, museums and parks. For instance, about 80 percent of SoHo’s galleries are located within the Cast Iron Historic District (Figures 3-4).

Figure 3 – Gallery in Cast Iron Historic District, SoHo

Source: Photo taken by author

Figure 4 – SoHo galleries (1990-2003)

Source: Manhattan Gallery Database

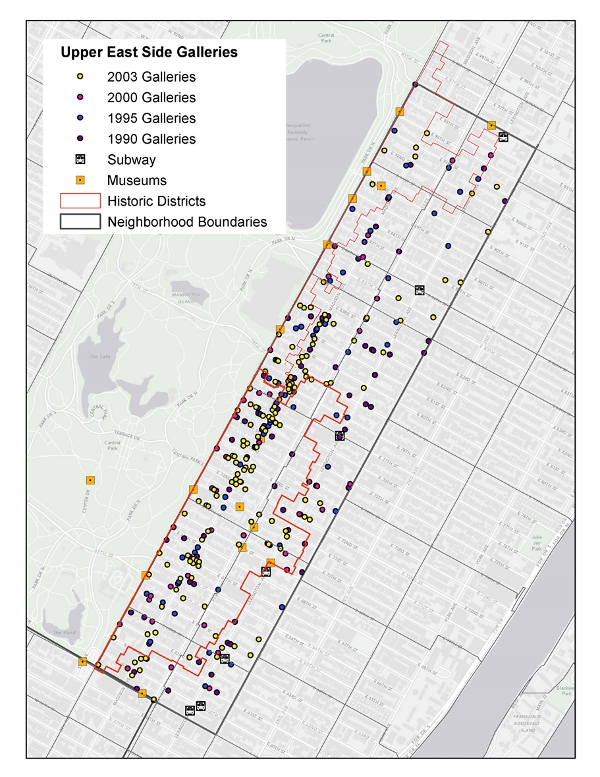

The high-ceilinged and large-windowed structures were originally built for manufacturing and today contain upscale apartments, restaurants and shops, as well as galleries. Galleries on the Upper East Side also occupy historic structures, mostly elegant 19th century townhouses, and are located near prestigious museums (the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim and the Frick) and Central Park (Figure 5-6).

Figure 5 – Upper East Side galleries in historic townhouses

Source: Photo taken by author.

Figure 6 – Upper East Side galleries (1990-2003)

Source: Manhattan Gallery Database

Starving artists may seek out low-rent, bohemian enclaves, but art galleries prefer to locate among well-to-do households. New galleries are more likely to open in neighborhoods with affluent, college-educated households and above-average rents. These trends are particularly pronounced for star galleries – perhaps not surprising, given the price of an original Matisse or Jeff Koons.

To determine whether neighborhoods with high concentrations of “star” galleries undergo more physical transformations, conditional on the initial level of amenities, I perform a variety of statistical analyses. Based on the evidence of previous case studies, we would expect gallery-rich neighborhoods to be especially dynamic, undergoing more frequent redevelopment. Gallery neighborhoods may also shift from industrial uses or vacant buildings towards mainstream residential and retail activity. If galleries increase nearby property values, the quantity of building stock should increase (in the form of more or taller buildings).

The results indicate that star galleries do not lead to neighborhood redevelopment, once initial amenities are controlled for. The simplest statistical models show a positive correlation between initial density of star galleries on Manhattan city blocks and several metrics of physical change. City blocks near many star galleries have a higher incidence of overall building changes, increased land shares devoted to residential and retail uses, and larger gains in aggregate building stock. However, these correlations are not robust to more sophisticated models, which control for initial physical and economic conditions. The results suggest that star galleries choose locations that subsequently undergo more transition, but redevelopment is due to observable and unobservable amenities, rather than galleries themselves.

Two policy implications emerge from this research. First, this study focuses on one type of arts venue in one city, but cannot speak to potential impacts across other cultural activities or other cities. Policymakers should rely on hard evidence when designing economic development strategies, targeting public funds to activities and locations that provide the greatest return. Second, should the arts be subsidized as a tool for economic development, or because they contribute other benefits to society? Does the value of La bohème extend beyond Rodolfo’s now-gentrified garret?

This article is based on the paper ‘Do art galleries stimulate redevelopment?’, in the Journal of Urban Economics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics, and do not indicate concurrence by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1wik7ZG

_________________________________

Jenny Schuetz – Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Jenny Schuetz – Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Jenny Schuetz is an Economist in the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Her research focuses on urban economics, real estate and housing policy. Jenny received a PhD in Public Policy from Harvard University, a Master’s in City Planning from M.I.T., and a B.A. with Highest Distinction in Economics and Political and Social Thought from the University of Virginia. Her current projects include a study of transit-oriented development in Los Angeles and an evaluation of the federal Neighborhood Stabilization Program.

Thanks for such an examination re: this topic on urban economic impacts from galleries. I would only point out that instead of the arts being a tool for “economic development” or as an example of an “economic development strategy”, I would substitute the word “business” for “economic”, as the focus here is upon transactional business activity, rather than upon socioeconomic development, which is the proper focus of community economic development. This distinction is critically important from a conceptual & human development standpoint, in my view.

Do I detect a little justification based guilt here? And from the one comment, economic development, “economic development strategy” business, so forth and so on. What are you people talking about. From a gentrified out resident of a historically poor neighborhood.