On December 9th, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released the executive summary of its longer report into the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) use of ‘enhanced interrogation methods’ after 9/11. Jennifer Kibbe writes that the report is replete with examples of the CIA’s inaccurate representations concerning its programs, and its lack of cooperation with the committee’s investigation. She argues that the report illustrates the difficulties that Congress faces in holding highly secretive agencies such as the CIA to account.

On December 9th, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released the executive summary of its longer report into the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) use of ‘enhanced interrogation methods’ after 9/11. Jennifer Kibbe writes that the report is replete with examples of the CIA’s inaccurate representations concerning its programs, and its lack of cooperation with the committee’s investigation. She argues that the report illustrates the difficulties that Congress faces in holding highly secretive agencies such as the CIA to account.

Is it possible to have both secret intelligence agencies and real democratic government? The way the United States has tried to square this circle is by creating a robust system of Congressional oversight of intelligence. But the report released earlier this month by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) about its investigation of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program sends a paradoxical message about how well that system is working and what it means for American democracy.

On the one hand, the report is, as noted governmental transparency advocate Steven Aftergood commented, “a remarkable demonstration of the congressional oversight function.” It is, on some level, astounding that the committee had access to over 6 million CIA documents and produced a report that runs to more than 6000 pages with more than 35,000 footnotes. That all implies a remarkable degree of access to the secret side of government, which in many countries is impenetrable.

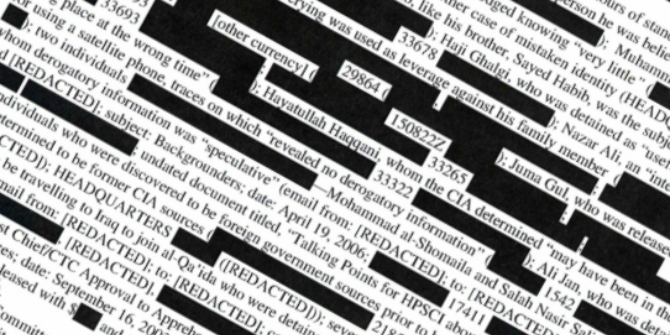

On the other hand, the report, or at least the 500 page executive summary that was declassified on December 9th, is replete with evidence of how hamstrung the system of Congressional oversight of the intelligence community really is. Evidence of these constraints runs throughout the report to such an extent that it makes the report’s own conclusion that “The CIA has actively avoided or impeded congressional oversight of the program” seem rather tame. Consider that the report includes a 37-page Appendix 3 that catalogs examples of “Inaccurate CIA Testimony to the Committee” from just one day, April 12, 2007. Although the executive summary never directly accuses the CIA of lying, it is an impressive study of how many ways one can characterize lying without using the word. For instance, on April 18, 2002, the CIA informed the SSCI that it “ha[d] no current plans to develop a detention facility.” As the report dryly notes, “[a]t the time of this representation, the CIA had already established a CIA detention site in Country [redacted] and detained Abu Zubaydah there.” There are also ample references to “inaccurate representations,” “inaccurate claims,” and “inaccurate information.” Suffice to say that the word “inaccurate” shows up no less than 263 times in the report.

There is also the issue of the CIA’s cooperation, or lack thereof, with the committee’s investigation. Yes, the committee was granted access to more than 6 million pages of internal CIA documents, but the CIA still held back more than 9000 pages that the committee specifically requested. Moreover, the CIA was caught spying on the committee staff’s computers during the investigation—hardly the stuff that robust oversight is made of.

But, the evidence of the ineffectiveness of Congressional oversight of intelligence goes deeper than the CIA (repeatedly) telling the intelligence committees untruths and trying to foil a particular investigation. In cases of covert action, the way the oversight process has evolved means the CIA is only required to notify the so-called Gang of 8, i.e., the chair and ranking member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI), the chair and vice chair of SSCI, and both party leaders in each chamber. While this was supposed to be a compromise that allowed CIA officials anxious to protect their covert operations to do so while still keeping a minimal number of members of Congress in the loop, the current report reveals the extent to which this setup makes a sham of the oversight process.

For instance, the CIA first briefed HPSCI’s leadership about the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” in early September 2002. The CIA’s draft record of the briefing at first noted that “HPSCI attendees […] questioned the legality of these techniques if other countries would use them.” Yet, the report found evidence that a CIA legal official deleted that sentence from the briefing record. The report also notes in several places how the two intelligence committees do not have any record of their own of these briefings (per CIA ground rules). So, not only is Congress reliant on the CIA for records of these briefings, but the CIA apparently doctors them at will.

The CIA did not brief SSCI’s leadership about its “enhanced interrogation techniques” until late September 2002, nearly two months after they had begun using them on Abu Zubaydah. The report goes on to note that after that briefing, Chairman Sen. Bob Graham (D-Fl) made “multiple and specific requests” for further information on the program and that internal CIA emails “describe efforts by the CIA to identify a ‘strategy’ for limiting the CIA’s responses to Chairman Graham’s requests for more information … specifically seeking a way to ‘get off the hook on the cheap.’” In the end, CIA officials just simply ran out the clock and did not respond to Graham’s requests before he left the committee in January 2003.

Senator Jay Rockefeller (D-WV) had a similar experience after becoming the Vice Chair of SSCI in 2003: “The CIA refusedto provide me with additional information I requested about the program…. The briefings I received provided little or no insight into the CIA’s program. Questions or followup requests were rejected, and at times I was not allowed to consult with my counsel or othermembers from my staff.” What Rockefeller and Graham and other members of the Gang of 8 were also up against were the other ground rules of being informed about covert action: that you are not allowed to discuss the information with other members of the committee, the committee’s counsel, subject matter experts, the media or the public. And yet, CIA and Bush administration officials point to these “briefings” as evidence not just that the Congressional intelligence committees were notified, but also that they consented to the program. (They never mention that the Congressional members have no veto power over covert actions.)

It is easy to understand why the CIA wants to protect such sensitive operations but having agencies capable of running such secret operations in a democracy requires that the legislative branch, as the public’s representative, be able to exert some level of meaningful oversight. This report has only confirmed what many have long feared: that even when members of Congress are motivated to try to oversee the CIA, the Agency simply has an overwhelming advantage that it is often all too willing to exploit.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.APP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1vjJmZo

_________________________________

Jennifer Kibbe – Franklin & Marshall College

Jennifer Kibbe – Franklin & Marshall College

Jennifer Kibbe is an Associate Professor of Government at Franklin & Marshall College. Her research interests are in covert action and congressional oversight of the intelligence community. Her most recent piece is “The Military, the CIA and America’s Shadow Wars,” in Shoon Murray and Gordon Adams, eds., Mission Creep: The Militarization of US Foreign Policy? (Georgetown, 2014).