Control of the floor agenda in the U.S. House of Representatives is integral if the majority party wishes to achieve its political and electoral aims. In new research, Jamie L. Carson, Michael H. Crespin, and Anthony J. Madonna find that parties will call on their members’ support during important procedural votes – which influence what is discussed, and the scope and length of the debate – when it is unlikely that voters will punish members for their support. However, despite these party pressures, members’ support is not guaranteed – more moderate and conservative members are less likely to support the leadership when requested.

Control of the floor agenda in the U.S. House of Representatives is integral if the majority party wishes to achieve its political and electoral aims. In new research, Jamie L. Carson, Michael H. Crespin, and Anthony J. Madonna find that parties will call on their members’ support during important procedural votes – which influence what is discussed, and the scope and length of the debate – when it is unlikely that voters will punish members for their support. However, despite these party pressures, members’ support is not guaranteed – more moderate and conservative members are less likely to support the leadership when requested.

Proponents of partisan influence in the United States House of Representatives believe that legislative outcomes can be manipulated for both electoral and policy benefits. Generally, these scholars argue that party organizations accomplish this through their control of the agenda-setting process. Underlying these theories is the assumption that the rank-and-file will vote with the party leadership on important agenda setting procedural votes in order to promote the desired outcome. Recent empirical work has confirmed the theoretical intuition that these procedural votes are of the highest priority to party organizations.

The theory underlying increased party pressure on procedural votes is two-fold. First, these votes allow the majority party to bring certain issues to the floor, regulate the scope of the substance under consideration, and control the length and nature of the debate. There is ample anecdotal evidence demonstrating that leaders will attempt to punish members who defect on procedural votes. For example, in 2008, House Appropriations Chairman David Obey (D-WI) cancelled a meeting with constituents from the office of Rep. Charlie Melancon (D-LA). Melancon had defected on a vote to order the previous question on a special rule the day before, leading Obey to tell the party caucus that “anybody who wants to routinely vote against the leadership on procedural grounds, don’t ask me to see their visiting firemen when they’re in town.”

Second, scholars note that procedural votes lack the “traceability” of amendment or final passage votes. As such, constituents are less likely to punish representatives for supporting the party’s position on a procedural matter. This traceability thesis provides a foundation for much of the research on legislative politics that argues the majority party can use their control of the agenda-setting process to bias policy output away from the chamber median.

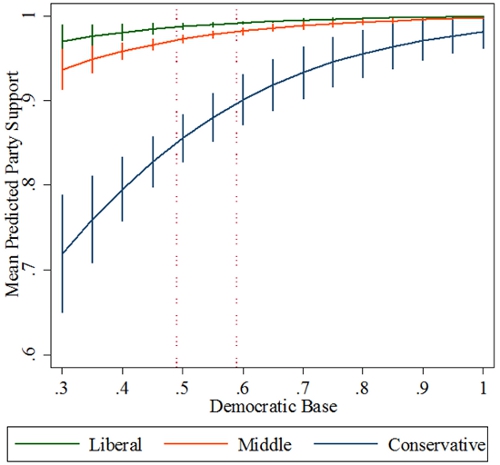

We examine this issue by taking advantage of a set of Democratic Leadership Office emails that signal the leadership’s positions on floor votes for parts of the 110th and 111th Congresses. We find that while leadership is most likely to call for support on certain procedural votes that (1) may be said to lack traceability (in contrast to votes on substantive policy, like amendments or final passage of a bill); (2) are of the highest importance to the majority party (i.e. previous question votes on special rules, votes on the final passage of a special rule); and (3) the majority has time to evaluate (i.e. motions to recommit yield a low percentage of signals), party support on those votes is by no means guaranteed. We find that while the most liberal members of the party vote with the leadership on procedural votes at high rates and nearly 100 percent of the time when signaled by the majority leader, moderate members are significantly less likely to support the party and are not responsive to these signals. This is demonstrated in Figure 1, which plots the predicted support on signaled votes for members who are more conservative than the floor median (blue), more liberal than the party median (green), and between the floor and party medians (red). It is clear from the figure that the members who are more conservative than the floor median are less likely to support the leadership when requested.

Figure 1 – Predicted Support (Signaled only)

In our view, defections on procedural votes make a great deal of sense despite the perceived lack of traceability. The traceability thesis suggests that members will be attacked for individual votes. However, in modern elections candidates are frequently attacked by opponents and interest groups for their aggregate voting record. For example, in 2010, Republican candidates attacked Representative Martin Heinrich (D-NM) for voting with then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi 97% of the time, Representative John Boccieri (D-OH) 93% of the time and Representative Glen Nye (D-VA) for voting with Pelosi 83% of the time. Rep. Gene Taylor (D-MS) supported John McCain’s presidential campaign in 2008, but he was still accused of voting with leadership 82 percent of the time in the lead up to the 2010 elections.

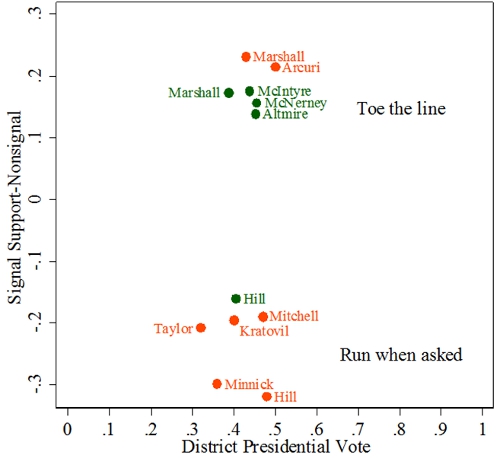

We might expect members in highly competitive districts—like Taylor—to be most vulnerable to these sorts of attacks. In Figure 2, we plot the difference in signaled and non-signaled support scores for some outlying representatives for the 110th (green) and 111th (red) Congresses. These members represented districts where the Democratic candidate for president received 50 percent or less of the vote but exhibited clearly different strategies in heeding the call of the party. Since they all serve in districts with a substantial number of Republican voters, being viewed as beholden to the party leadership is typically not the best way to secure reelection.

Figure 2 – Signal Responsiveness

Although these legislators represent competitive districts, the members in the top group are clearly toeing the party line on key procedural roll calls. When the leadership sends signals, they increase their support by between 14 and 23 percent compared to non-signaled votes. Since the average baseline of support starts above 90 percent, this is a pretty substantial uptick.

Representatives in the bottom grouping appear to run away when asked for support. Unlike the average member, these representatives vote with the party at lower rates on votes like moving the previous question or passing a special rule. Although we can only speculate, it is plausible they are trying to deliberately lower their party support scores to avoid ads that compare their aggregate voting record with the Speaker of the House (in this case, Nancy Pelosi).

Did either strategy pay off? Clearly neither was enough to overcome Republican waves in competitive districts and of the 10 members in the figure, only one is now serving in the current 114th Congress. Running away may have helped Jerry McNerney (D-CA) as he defeated Republican David Harmer in 2010 and then moved to a safer district in 2012. Mike McIntyre (D-NC) won his 2012 election by 654 votes but retired at the end of the 113th Congress. The remaining members were all defeated one way or another. Given this, in our view it is not the perceived lack of traceability that yields high—though not absolute—support for the majority party on important procedural votes, but the observation for most vulnerable members that a wave election will likely drag you under no matter how fast you try to swim away from leadership.

This article is based on the paper ‘Procedural Signaling, Party Loyalty, and Traceability in the U.S. House of Representatives’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image: Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) Credit: Senate Democrats (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Des3ML

_________________________________

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie Carson is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at The University of Georgia. His primary research interests are in American politics and political institutions, with an emphasis on representation and strategic political behavior. Most of his current research focuses on congressional politics and elections, American political development, and separation of powers.

Michael H. Crespin – University of Oklahoma

Michael H. Crespin – University of Oklahoma

Michael Crespin is the Associate Director of the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center and Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oklahoma. His research focuses on legislative politics, congressional elections, and political geography.

_

_

Anthony J. Madonna – University of Georgia Anthony Madonna is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Georgia. His research interests include American political institutions and development, congressional politics and procedure and presidential politics.

Anthony J. Madonna – University of Georgia Anthony Madonna is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Georgia. His research interests include American political institutions and development, congressional politics and procedure and presidential politics.