Election laws are not uniform across the U.S.; many states differ in their approaches to when you are able to register to vote, and whether you can vote on Election Day. In new research, Alex Street examines the impact of legislation which prevents people from registering to vote in the lead up to the election. Using data on Google searches for “voter registration”, and comparing this with voter registration data he finds that if registration had been allowed up to and including Election Day, then between three and four million people could have registered to vote, which would have increased turnout by 3 percent.

Election laws are not uniform across the U.S.; many states differ in their approaches to when you are able to register to vote, and whether you can vote on Election Day. In new research, Alex Street examines the impact of legislation which prevents people from registering to vote in the lead up to the election. Using data on Google searches for “voter registration”, and comparing this with voter registration data he finds that if registration had been allowed up to and including Election Day, then between three and four million people could have registered to vote, which would have increased turnout by 3 percent.

Voter registration rules in the USA differ from those in the UK and most of Europe. In the UK the government maintains the electoral roll, and registration is mandatory. In the USA, however, the responsibility for registering generally lies with the citizen. One in seven Americans is not registered to vote. The rules for registering are set by state and local governments, and differ widely across the country. The details of how elections are administered can have big political effects. In new research (ungated) I use data from Google to study the impact of registration laws on voter turnout. I find that laws which restrict registration may have prevented up to four million Americans from registering to vote in the 2012 elections.

Historically, local discretion over election laws gave politicians opportunities to affect the size and composition of the electorate. In the 19th century several states in the Midwest extended the right to vote to non-citizens who declared an intention to naturalize. This was part of an effort to encourage people to settle in these areas. In contrast, voter registration laws were also used to disenfranchise African Americans in Southern states after the Civil War. Outright discrimination was combined with measures that affected mainly the former slaves and their descendants, such as the poll tax or literacy tests.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 put an end to many of the discriminatory rules, and reduced the variation in voter registration laws across the country. But stark differences remain. Since the Supreme Court weakened the VRA in 2013, several states with a history of discrimination have introduced new requirements, such as voter ID laws. This has drawn criticism because members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to hold the accepted forms of ID.

Court cases over voter ID laws have been in the news recently, even as America marked the 50th anniversary of brutal police attacks on Civil Rights activists in Selma, Alabama, which inspired the passage of the VRA.

Less attention has been paid to other aspects of voter registration laws, even though scholars continue to debate their effects. In particular, there are still big differences across the states in the deadlines that are imposed on voter registration. For the 2012 presidential election, a dozen states allowed voters to register on Election Day. But other states closed registration as much as a month before the election and in the typical state the registration period ended three weeks before voting began.

Closing voter registration in the final weeks of the campaign prevents new voters from being mobilized, in the very period of greatest interest in the election. It may seem obvious that this reduces turnout. But skeptics have argued that most of the people who are actually interested in voting are able to get their act together and register before the deadline.

My research takes a new approach to answering the question of how many people are interested in registering to vote, after the deadline has passed. Working with a statistician and with engineers at Google, I used web searches for “register to vote” and similar terms to measure last-minute interest in the run-up to the 2012 elections. It turns out that such queries were entered millions of times, especially in the final few days of the campaign.

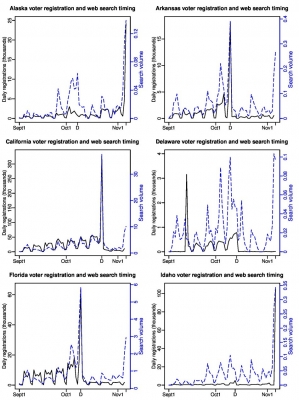

In order to estimate the link between web searches and the number of people who might register, we turned to state records that include the date on which people registered. We find that the daily numbers of web searches and of voters registered, in each state, were closely related. This pattern is illustrated in the figure below, for a handful of states. Alaska and Idaho allowed Election-Day Registration (EDR) in 2012. But we also see late spikes in search activity in Arkansas, California, Delaware and Florida, after the registration deadline had already passed.

Figure 1 – Voter registration and web search timing (click to enlarge)

Note: Web searches for “voter registration” and daily registration totals, from September to November 2012. Black lines and left axes show daily registrations, in thousands. Dashed blue lines and right axes show standardized search volume. Horizontal axes show dates. D marks the mail and in-person registration deadlines, which are the same day in most states, although some EDR states also have an earlier mail deadline.

If the same relationship between web searches and actual registration had been allowed to continue up to Election Day, we estimate that an additional three to four million Americans would have registered to vote. This would have added 2 percent to the number of registered voters, and, since late registrants vote at high rates, would have added 3 percent to turnout. These numbers would not flip the outcome of very many elections. But there would be intrinsic benefits to allowing several million more people to vote.

More broadly, this research illustrates how we can use the mountains of new data generated by online behavior to study voting and elections. Searching online is now the obvious way to seek political information, and data about web searches promise to help us understand both the causes and likely consequences of such enquiries. What inspires people to learn about politics? How is information-seeking affected by the context of political campaigns or election laws? We now have new tools to answer these open questions.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Estimating Voter Registration Deadline Effects with Web Search Data’, in Political Analysis.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1O9E9fN

_________________________________

About the author

Alex Street – Carroll College

Alex Street – Carroll College

Alex Street is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Carroll College in Helena, Montana. He studies political behavior and immigrant politics in Europe and the USA. His research has been published in journals such as Political Analysis, World Politics, and Political Research Quarterly.