In 2001, Congress enacted the No Child Left Behind Act, with the aims of improving student’s academic achievement and closing the achievement gap between high and low achieving students. In new research, Vladimir Kogan, Stéphane Lavertu and Zachary Peskowitz assess the impact of the measure’s school and district performance metrics. They find that changes in the measure’s ‘adequate yearly progress’ metric meant that disadvantaged schools districts which had actually seen improvements in student achievement were less likely to pass a school tax levy, starving these districts of the resources needed to educate low achieving students.

In 2001, Congress enacted the No Child Left Behind Act, with the aims of improving student’s academic achievement and closing the achievement gap between high and low achieving students. In new research, Vladimir Kogan, Stéphane Lavertu and Zachary Peskowitz assess the impact of the measure’s school and district performance metrics. They find that changes in the measure’s ‘adequate yearly progress’ metric meant that disadvantaged schools districts which had actually seen improvements in student achievement were less likely to pass a school tax levy, starving these districts of the resources needed to educate low achieving students.

Over the past two decades, U.S. state and federal education policy has increasingly focused on accountability — measuring student performance and requiring school districts to implement reforms when achievement falls short. One key mechanism for holding educators accountable is the public dissemination of information on student achievement through official school report cards. All U.S. states have published annual report cards rating local schools and districts since the early 2000s.

The argument for report cards seems simple enough: With timely information on student performance, school and district personnel can identify struggling student subgroups and areas for improvement and parents can make more informed decisions about their children’s education. Yet, as we show in new research, report cards can have perverse consequences on community perceptions of local schools.

Consider one recent example from New York City: For many years, New York issued annual report cards assigning each of its public schools a grade ranging from “A” to “F,” reflecting the achievement of students attending them. In 2009, however, New York’s education chancellor decided the report cards needed a shake-up, because 97 percent of the city’s schools were receiving an “A” or a “B.” The following year, the city raised its education standards and some schools received lower grades. Subsequent surveys of parents showed that these lower grades had a dramatic impact, reducing parents’ reported satisfaction with their local schools even though student achievement in these same schools actually increased from the year before.

Something similar happened in Florida. When the state changed its school rating system a few years ago, some schools received a lower grade. This reflected a change in measurement, not a decline in underlying student achievement. Yet once again, parents took notice and donations to schools receiving lower marks dropped significantly.

The experiences of these two states suggest that how performance information is presented on school report cards can influence the beliefs of residents about their local schools. This is news that many education reformers are likely to find heartening. Unfortunately, these cases also suggest that local communities might respond to negative information about schools not by redoubling their efforts to improve student instruction, but rather by withdrawing their support.

This should be kept in mind by policymakers. In our research, we find that a flawed interpretation of report card information by voters in one U.S. state, Ohio, appears to have undermined public schools by making it harder for some local districts to raise local revenues.

In particular, our study focused on the impact of the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act’s (NCLB’s) school and district performance metrics. The law had two goals — to increase overall academic achievement among U.S. students and to close the achievement gap between high-achieving and struggling students. It required that all students to be proficient in math and reading by 2014 and that schools make “adequate yearly progress” (AYP) toward this goal. If schools failed to make AYP for at least two years, the law imposed a series of escalating sanctions, ranging from allowing students to transfer to better-performing schools to requiring major school restructuring, such as replacing the principal and a majority of teachers.

Although much of the focus has been on these sanctions, NCLB’s annual AYP designations were widely disseminated by the media and appeared on Ohio’s annual report cards. We analyzed every school district levy election from 2003 to 2012 to see whether a district’s AYP status affected the willingness of voters to fund their local schools.

Our results showed overwhelmingly that they did: School districts receiving a negative AYP designation were about 10 percent less likely to pass a school tax levy. This was also true within school districts over time. In years when a school district made AYP, it had an easier time passing levies than in years when it fell short. In many cases, such over-time changes in district AYP status were driven by seemingly arbitrary changes in how AYP was calculated, as opposed to actual changes in how well districts educated students. That’s how we know that voters were responding to the federal indicator of school performance rather than the underlying student test scores that determined them.

Interestingly, these effects undermined the very intent of the federal law. The AYP calculation did not account for significant differences in knowledge between students before they ever set foot in a classroom. Poor and minority students begin school well behind their peers. Even when these students had effective teachers and attended excellent schools — learning more during the year than their wealthier peers — they often failed to reach the AYP performance benchmark.

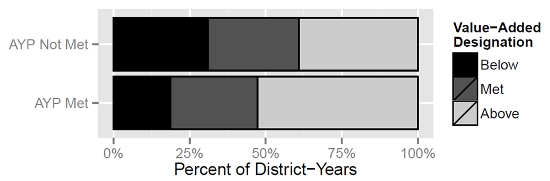

In Ohio, we found that 70 percent of school districts deemed to be “failing” by the federal government were actually average or above average in terms of how much their students were learning (see Figure 1). Their students were making significant gains, but not enough to receive a favorable AYP designation. Consequently, these districts suffered financially. Voters took account of the federal designation when voting on levies, but they did not appreciate its limitations.

Figure 1 – Student learning and AYP designations

Because school districts serving a larger number of disadvantaged students were most likely to receive negative AYP designations, the federal law appears to have undermined its purported goal of closing achievement gaps. Instead, AYP’s impact on levy outcomes starved districts of essential resources needed to educate low achieving students.

As we write this, Congress appears close to reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and it seems all but certain that the law will continue to require states to issue annual report cards. Our findings offer important lessons for policymakers about how best to do so to avoid the unintended consequences that we have identified:

- Public education is inherently political. Local school board members must stand for election, and in states like Ohio, voters intervene directly to determine the revenues available to local schools. It is important to take into account the unintended political impacts of performance information when designing school report cards.

- Although there is strong evidence that high-quality teachers can have a real impact on their students, it is also true that much of the variation in student achievement is explained by factors beyond the control of local schools. After all, children spend a small fraction of their first 18 years in the classroom, and what they do in the summer, after school, and on the weekends has a much bigger impact on their test scores than their local schools.

If the goal is to provide parents and local voters with information about how local educators are doing, report cards should focus not on achievement levels (as NCLB did) but rather on student growth. Focusing on how performance changes over time focuses attention on the portion of student achievement that is actually determined by the quality of their schools.

- It is important to understand how voters and parents process information, and to account for the systematic biases in their assessments. We found that district designations have a much bigger impact on levies appearing on the November ballot, the elections that take place shortly after the yearly report cards are released. Over time, however, voters’ memories fade. Indeed, we found that after one year, voters seem to ignore the previous performance information.

Improving public schools is an important public policy goal. Indeed, it is necessary to ensure our long-term economic growth and national security. But it is also essential that we design accountability systems in a smart way, taking account of the unintended political consequences.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Performance Federalism and Local Democracy: Theory and Evidence from School Tax Referenda’ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1GAv2QY

_________________________________

Vladimir Kogan – Ohio State University

Vladimir Kogan – Ohio State University

Vladimir Kogan is an assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Department of Political Science.

_

Stéphane Lavertu – Ohio State University

Stéphane Lavertu – Ohio State University

Stéphane Lavertu is an associate professor at Ohio State’s Glenn College of Public Affairs.

_

Zachary Peskowitz – Emory University

Zachary Peskowitz – Emory University

Zachary Peskowitz is an assistant professor at Emory University’s Department of Political Science.

2 Comments