Many lobbying groups from across the ideological spectrum provide assistance to state legislators in drafting bills – but does this practice help the spread of ideas and best practice across the states? In new research which compares the similarity of laws across states, Joshua Jansa and Kristin Garrett find that many bills are highly plagiarized from lobby groups’ model bills. They argue that this ‘copy and paste’ approach to legislation throws the states’ role as ‘laboratories of democracy’ into question.

Many lobbying groups from across the ideological spectrum provide assistance to state legislators in drafting bills – but does this practice help the spread of ideas and best practice across the states? In new research which compares the similarity of laws across states, Joshua Jansa and Kristin Garrett find that many bills are highly plagiarized from lobby groups’ model bills. They argue that this ‘copy and paste’ approach to legislation throws the states’ role as ‘laboratories of democracy’ into question.

This past May in Savannah, Georgia, legislators from across the country met with representatives of the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, as part of a Spring Task Force meeting. While there, ALEC officials, allied corporate lobbyists and donors, and state legislators discussed ways to advance an agenda of limited government and free markets. Not only were ideas exchanged, but also model legislation. ALEC is one of several organizations that produce model legislation—pre-written bills that can be introduced in any state—as part of its lobbying strategy. While ALEC has garnered a reputation as a prolific “bill mill” for the large amount of pro-business model bills it provides to legislators, groups as diverse as Americans United for Life (AUL), Gay, Lesbian, & Straight Education Network (GLSEN), and SIX (State Innovation Exchange: the liberal counter to ALEC) have used model legislation to shape policy across the states.

The use of model legislation by state legislators presents a conundrum for the academic literature on the spread of policies across the states. Existing theories support the idea that professional organizations and interest groups help create an information network that aids the spread of policy ideas. The majority of studies, however, only consider state-to-state borrowing of policy ideas. The predominant methodology—event history analysis—limits scholars to examining whether a state adopted a policy or not. In order to study the influence of outside organizations, scholars need a measure of how similar the texts of laws are to model bills.

In recent research, we use a blend of text and network analysis to understand from whom states are borrowing bill language—is it other states, or interest groups? We argue that state legislators are likely to look to interest group model bills when crafting legislation because legislators and their staffs are time-constrained political experts who look to outside organizations for the legal language to put policy ideas into law.

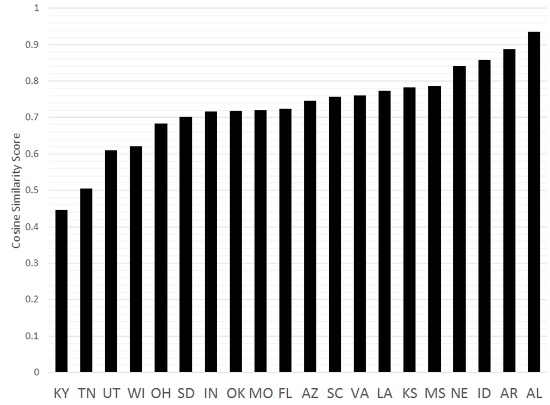

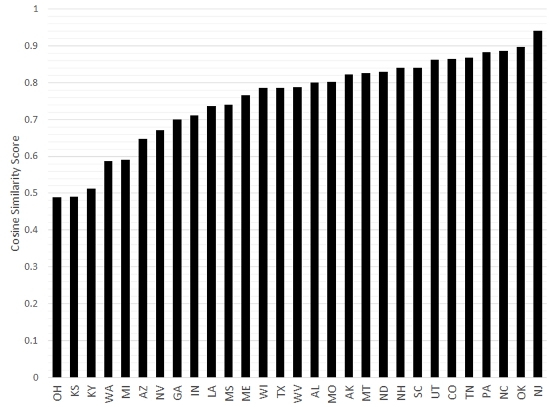

To test our argument, we collected all bills adopted into law for two different policies—abortion insurance coverage restrictions and the justifiable use of force (sometimes referred to as the Castle Doctrine or Stand Your Ground laws). Abortion coverage restriction model bills were promoted across the states by AUL shortly after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Stand Your Ground was spread through model legislation by ALEC, following Florida’s adoption of a similar provision in early 2005. We then compared all the laws for each respective issue to one another. To do this, we used a plagiarism detection technique called cosine similarity, which produces a similarity score that ranges from 0 to 1. Scores closer to 1 indicate that two texts are more identical to one another.

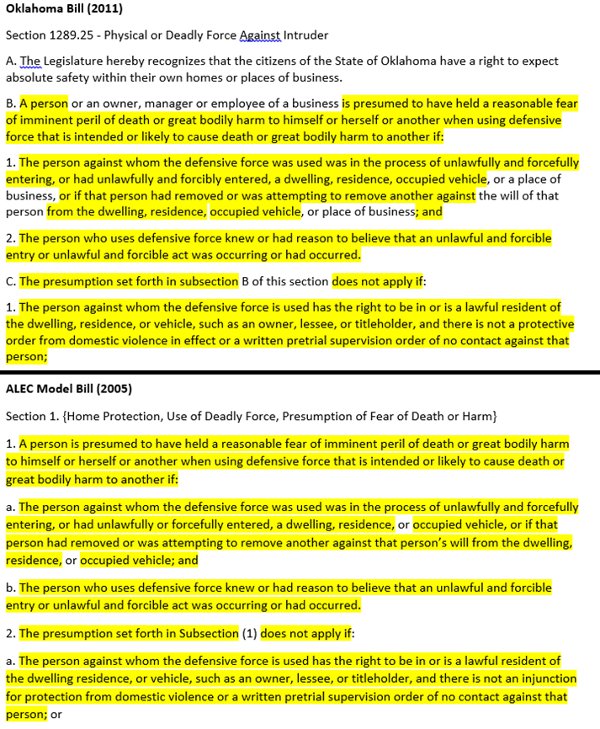

Figures 1 and 2 present the similarity scores among adopting states for each policy. Some states heavily borrowed language when writing their bills, including phrases from interest group model bills. Others were more original in their bill texts. One example of a law that was highly similar to model legislation is Oklahoma’s justifiable use of force provision, adopted in 2011. Entire passages are copied word for word from ALEC’s 2005 model legislation. While some differences exist, such as Oklahoma’s inclusion of business owners into the ALEC framework, Oklahoma’s law is highly plagiarized from ALEC’s model bill. The cosine similarity score between the two is 0.948.

Figure 1 – Similarity to previous adopters on abortion coverage restrictions

Figure 2 – Similarity to previous adopters on stand your ground legislation

We then used the scores to draw a social network that connected states to the state or interest group that its law was most similar to. What we found was that for both abortion restrictions and Stand Your Ground, the interest group was the most central actor in the network. What this means is that, for these two issues, state legislators tended to seek out interest group model legislation as a basis for writing their own legislation, not the policy experiments of other states.

Our findings have important implications for the scholarly and popular understanding of the states as “laboratories of democracy.” On the policies we studied, language developed by unelected groups provided the foundation for many state laws. If policy is copied and pasted from interest group models into law, we have to question whether states are fulfilling their roles as policy experimenters. Instead, state legislatures may simply be following national ideological or professional legislative agendas.

Ongoing work continues to uncover effects of model legislation on state lawmaking. Joshua Jansa, Eric Hansen, and Virginia Gray extend the plagiarism detection technique to a broad set of 12 issues. We find that state laws are more similar to one another when there is model legislation available on the issue, all else equal. Mary Kroeger uses a different method of plagiarism detection to analyze why legislators introduce model bills. She finds that legislators with more experience, resources, and conservative ideology are more likely to introduce ALEC model bills.

This exciting line of research provides new insights into weaknesses in the federal system’s ability to localize interest group influence. In Federalist #10, James Madison theorized that the “mischiefs of factions” would be contained locally because of the size and diversity of the Union. However, we find that organized interests can have a substantial impact on policy making across the United States by promoting pre-written laws on a state by state basis. Interest groups can affect change nationally by providing an important service to state lawmakers—writing bills for them.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Interest Group Influence in Policy Diffusion Networks’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Tony Webster (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1hCw764

_________________________________

Joshua Jansa – University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Joshua Jansa – University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Joshua Jansa is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. His research interests include interest groups, state politics, economic policy, and inequality.

Kristin Garrett – University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Kristin Garrett – University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Kristin Garrett is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Her research interests include public opinion, morality and politics, religion and politics, and research methods.

1 Comments