After 2001’s 9/11 attacks, public attitudes towards Muslims worsened, and concern increased about the perceived threat of Islamic radicalization in US prisons. But how has the news media portrayed Muslim prisoners in the US? In new research, which examines news reports over a 25 year period, Janani Umamaheswar finds that despite concerns over radicalization, newspapers tended to be nuanced and balanced in their coverage of Muslim inmates.

After 2001’s 9/11 attacks, public attitudes towards Muslims worsened, and concern increased about the perceived threat of Islamic radicalization in US prisons. But how has the news media portrayed Muslim prisoners in the US? In new research, which examines news reports over a 25 year period, Janani Umamaheswar finds that despite concerns over radicalization, newspapers tended to be nuanced and balanced in their coverage of Muslim inmates.

Following the 9/11 attacks, public attitudes toward Muslims living in the United States worsened considerably. Simultaneously, government officials sounded alarm bells about a looming threat of Islamic radicalization in the U.S. prisons. Prisons, members of this camp argued, were fertile breeding grounds for terrorists and radicals. Opponents of this view argued that radicalization of Muslim inmates is not very different from the process through which inmates are recruited into prison gangs, and that the threat of terrorist acts organized in prison is actually quite modest.

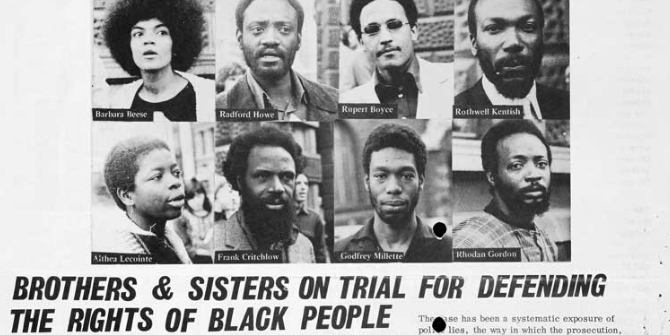

One way to interpret the prejudice that many Americans report feeling toward Muslims is by viewing it as a defensive response to perceived threats by members of a subordinate group—the key argument in a theory called the “minority threat” perspective. Sociologists have used the minority threat perspective to understand both race and religious prejudice. In the case of Muslim inmates, the prejudice may be both race- and religion-based, since many Muslim inmates in the U.S. are also African-Americans.

Despite research on media representations of Muslim-Americans, we know little about how the media portray Muslim prisoners in the U.S. Against the backdrop of growing fear of Islamic radicalization, in new research, I examined how over 150 newspaper reports published in the U.S. between 1987 and 2012 portrayed incarcerated Muslims. Considering the power of the media to convey social messages and shape public opinion, I examined reports published before and after the 9/11 attacks to investigate changes in the newspapers’ portrayal of incarcerated Muslims.

Based on the minority threat perspective, one might expect that newspaper reports will reflect (and maybe even feed) concerns regarding radicalization, especially among inmates. I was surprised, however, to find that the newspapers were unusually nuanced and balanced in their portrayal of Muslim inmates.

Both before and after the 9/11 attacks, the newspapers I examined focused heavily on the legal rights of incarcerated Muslims. Before 9/11, they factually described debates regarding incarcerated Muslim’s right to practice their religion freely. After 9/11, however, the articles shifted to focus heavily on the civil rights violations that many incarcerated Muslims reported. Using vivid, emotion-laden narratives from inmates themselves, the reports captured the fall-out of the war on terror on Muslim prisoners. Contrary to the minority threat perspective, the newspapers took seriously the issue of Muslim inmates’ civil rights violations, and they did not suggest that these were unequivocally justifiable because of a looming threat of terrorism. To some degree, therefore, the reports reflected a concern with raising public awareness of these violations in an effort to protect, rather than vilify, incarcerated Muslims.

While there was not a single mention of Islamic terrorism in U.S. prisons in newspaper reports published before 9/11, reports published after 9/11 focused far more heavily on the issue of prisoner radicalization. On the one hand, this is unsurprising, given the public concern with this issue. On the other hand, however, the reports’ analysis of this issue was surprisingly sophisticated. I say surprisingly because the media have repeatedly been criticized for perpetuating racial and religious stereotypes, for homogenizing entire sub-groups, and for presenting “one-sided” accounts specifically of the 9/11 attacks that suggest, perhaps misleadingly, that there is broad consensus about the events among journalists, politicians, and the public.

In contrast, the reports I analyzed did not make stereotypical generalizations about either Islam or incarcerated Muslims, and they drew careful distinctions between moderate and radical Muslims, even going as far as to note the rehabilitative impact that Muslim chaplains can have in the prison setting. While they included quotes from government officials who advocated a “whatever-means-necessary” approach to combating terrorism, they also used as sources scholars and other experts in Islam and Arab culture. The resulting reports captured the debate surrounding radicalization without the sensationalism, alarmism, and impulsive defensiveness one might expect based on the minority threat perspective.

We must be careful, however, not to assume simplistically that newspapers are wholly sympathetic toward Muslim inmates. The focus on the threat of Islamic radicalization emerged only after the 9/11 attacks, which is likely a reflection—and perhaps reinforcement—of public fear of Islam. Further, although many reports emphasized that Muslim chaplains can have a positive impact on inmates, many also noted the concern that these chaplains could be a radicalizing force in the prison environment. The newspapers’ distinctions between “moderate” and “radical” chaplains may be less indicative of an informed and well-rounded understanding of the Muslim community and more indicative of the media’s ability to define and categorize certain people as “friends” to the U.S. and others as “enemies.”

Finally, while the newspapers were commendable in their efforts not to describe the entire Muslim population in homogenous, stereotypical terms, many reports did portray Islam as a “cure” for struggling African-American inmates. The reports did not portray African-American inmates as threatening (as the media often have in the past), but this one-dimensional perspective of oppression and struggle again fails to capture the complex social and structural realities of incarcerated African-Americans.

The newspapers that I examined no doubt deserve credit for shying away from sensationalistic reports that exploit public fears of Islamic radicalization. However, there is still a need to move beyond simple categorizations toward a more critical examination of the lives of the many Muslims who are incarcerated in prisons and jails in the U.S. today. This issue is all the more pressing considering the complicated role that religion may play in individuals’ efforts to maintain crime-free lives upon their release from prison/jail.

This article is based on the paper, ‘9/11 and the evolution of newspaper representations of incarcerated Muslims’, in Crime Media Culture.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1TMHyE5

_________________________________

Janani Umamaheswar – Rider University

Janani Umamaheswar – Rider University

Janani Umamaheswar is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Rider University. She recently completed her PhD in the Department of Sociology and Criminology at the Pennsylvania State University, and her research interests are in the areas of gender, crime and deviance, incarceration, and the life course.