Recent theories about the rise of the ‘creative class’ suggest that skilled workers in knowledge-intensive jobs are attracted to cities which contain cultural amenities and a diverse population. In new research using Chicago census tract data, Bradley Bereitschaft and Rex Cammack test this theory. They find that neighborhood diversity is a weak predictor of where creative class workers chose to live, and that more traditional factors, such as home values, schools, and transport were more likely to predict a higher proportion of creative class workers in a neighborhood.

Recent theories about the rise of the ‘creative class’ suggest that skilled workers in knowledge-intensive jobs are attracted to cities which contain cultural amenities and a diverse population. In new research using Chicago census tract data, Bradley Bereitschaft and Rex Cammack test this theory. They find that neighborhood diversity is a weak predictor of where creative class workers chose to live, and that more traditional factors, such as home values, schools, and transport were more likely to predict a higher proportion of creative class workers in a neighborhood.

Richard Florida’s well-known, though widely critiqued, creative class theory suggests that highly skilled workers with creative- and knowledge-intensive occupations (e.g., science and engineering, technology, art and media, business and finance, law, medicine) are drawn to particular cities and neighborhoods primarily on the basis of so-called “quality of place” amenities. Thick labor markets, active social, cultural and entertainment scenes, and a tolerant atmosphere as approximated using indices of diversity are typically cited among the primary pull factors. Among these assets, diversity is often the most controversial in terms of its ability to attract creative class workers and catalyze economic growth.

Though research on the migration of creative workers between cities and regions have generally indicated that employment opportunities still outweigh all other considerations (including “quality of place” amenities), much less is known about what attracts the creative class to particular neighborhoods. Florida and other scholars have suggested that creative workers are more likely to exhibit a distinct preference for older, established neighborhoods that offer a stimulating urban lifestyle with a diversity of people and an array of potential experiences. Diversity may be particularly appealing to “footloose” creative workers who migrant between cities in search of better career prospects. These migrants may interpret diverse cities and neighborhoods as more welcoming to outsiders, with lower barriers to integration and acceptance, regardless of sexuality, race, or ethnicity.

Yet, are creative class workers more likely to live in diverse neighborhoods? If so, does the type of diversity matter? We set about answering these questions using demographic and employment data from 1,983 census tracts (a scale that provides a close approximation of urban neighborhoods in the US) across the central five counties of the greater Chicago region. Four types of diversity were examined: income, language, race, and sexual orientation as measured using the proportion of gay households per census tract. In addition to examining the creative class as one broad occupational group, we also looked at three creative class occupational sub-classes: computer/engineering/science (CES), education/library/training (ELT), and art/design/entertainment (ADE) occupations.

In the process of modeling the relationship between the creative class and neighborhood diversity it was necessary to control for other potentially attractive urban attributes and amenities including high home values, proximity to “top” grade schools and colleges/universities, availability of green/open space, access to rail depots, and proximity to “third places” such as coffee shops, bars/pubs, cafés, and bookstores.

An initial set of “global” regression models were used to examine the relationships between variables across the entire study area. Taken together, the models indicated that census tracts with a higher proportion of gay households and income diversity were statistically more likely to have higher concentrations of creative class workers. Census tracts with higher levels of linguistic and racial diversity, however, tended to have lower proportions of creative class workers overall, but a higher proportion of workers with CES occupations.

The results of the global modeling procedure suggest that the spatial associations between neighborhood diversity and the creative class vary by type of diversity as well as specific occupational grouping. Additionally, although neighborhood diversity proved to be statistically significant in several models, overall it was a relatively weak predictor of which census tracts creative class workers were likely to live in. Measures of neighborhood diversity with the highest explanatory power included percentage of gay households, which explained 6.5 percent of the variability in the proportion of workers with CES occupations, and linguistic diversity, which explained 3.2 percent of the variability in the proportion of workers with ELT occupations. This is quite low compared to several control variables including median home value, which accounted for 19 to 65 percent of the variability in creative class workers across all models.

To get a clearer picture of how the relationships between the creative class and neighborhood diversity vary throughout the Chicago study area, we utilized a popular new geographic technique known as geographically-weighted regression (GWR). In contrast to global regression models, which produce a single equation describing the relationships between independent and dependent variables, GWR generates separate equations for each individual observation – in this case, each individual census tract.

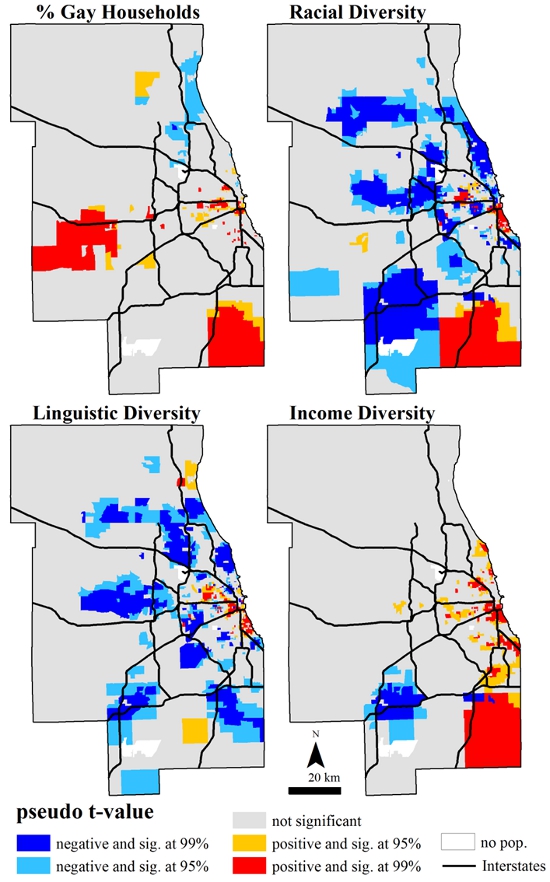

Overall, the predictive capability of the models increased significantly when using GWR, indicating that the strength and direction of the relationships between the creative class and neighborhood diversity often varied substantially across the study area. This can be seen in Figure 1, where the blue areas indicate negative associations between the creative class total and the indicated type of diversity, and the red and orange areas indicate positive associations. The relationships between the creative class and both racial diversity and linguistic diversity, for example, show similar patterns across the Chicago area with positive associations mainly south and west of downtown (including Bronzeville to the south and Oak Park to the west; Figure 2) and negative associations throughout much of the suburbs.

Figure 1 – Significant positive (red/orange) and significant negative (blue) associations between four types of neighborhood diversity and the proportion of workers with creative class occupations across the Chicago, Illinois study area.

Although neighborhood diversity appears to play a rather limited role overall in predicting where within Chicago creative class workers are likely to settle, the GWR analysis demonstrated that there exists considerable spatial variation in the strength of these relationships. This is not unexpected given the wide range of values and preferences within the creative class itself, and the shifting needs and desires that accompany different life-cycle stages. “Classic” locational factors (i.e., home values, top schools, proximity to transit & open space) were, in many models, much stronger predictors of the proportion of creative class workers per census tract, supporting the notion that “quality of place” amenities, including diversity, are at best secondary factors in the intra-urban location decision of creative class workers.

Figure 2 – Oak Park is one of the few neighborhoods in Chicago to exhibit a positive association between both racial and linguistic diversity and the proportion of workers with creative class occupations.

Photo credit: Bradley Bereitschaft

Crucially, the spatial relationships between diversity and the creative class observed in this Chicago case study were often negative, suggesting that polarization along racial and ethnic lines remains quite stubborn, even as many inner city neighborhoods undergo rapid socio-economic change. If the goal is to reduce spatial inequality and segregation, then the results of this study suggest that municipal (and regional where applicable) governments will need to be more pro-active in stimulating diversity while at the same time ensuring access to affordable housing when faced with “creative gentrification”.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Neighborhood diversity and the creative class in Chicago’, in Applied Geography, which is open access and free to read.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1RBuCAM

_________________________________

Bradley Bereitschaft – University of Nebraska at Omaha

Bradley Bereitschaft – University of Nebraska at Omaha

Bradley Bereitschaft is an Assistant Professor in the department of Geography/Geology at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. His research interests primarily concern issues of equity, livability, and sustainability in the urban environment.

Rex Cammack – University of Nebraska at Omaha

Rex Cammack – University of Nebraska at Omaha

Rex Cammack is an Associate Professor in the department of Geography/Geology at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. His areas of interest include cartography and geographic information systems.

1 Comments