Frustrated with legislative gridlock, many commentators have suggested term limits to ensure fresh ideas that will improve legislative efficiency. In new research which studies bill cosponsorship in 82 legislative chambers, Clint S. Swift and Kathryn A. VanderMolen find that term limits for legislators actually reduces bipartisan cooperation. They write that this stems from term-limited legislators’ fear that such cooperation will harm their future career chances in other parts of government.

Frustrated with legislative gridlock, many commentators have suggested term limits to ensure fresh ideas that will improve legislative efficiency. In new research which studies bill cosponsorship in 82 legislative chambers, Clint S. Swift and Kathryn A. VanderMolen find that term limits for legislators actually reduces bipartisan cooperation. They write that this stems from term-limited legislators’ fear that such cooperation will harm their future career chances in other parts of government.

Frustration with gridlock and perceptions of self-serving, greedy politicians has led to skyrocketing popularity for legislative term limits in the United States. Term limit advocates assume that new legislators are key to introducing the fresh ideas that will improve both legislative efficiency and reduce partisan wrangling. As a result, term limit reforms are seen as a means of alleviating partisan gridlock and addressing urgent state problems, particularly in states with high-stakes political battles.

Do term limits actually reduce the frequency of these highly partisan, gridlocked relationships among legislators, as proponents suggest? Our recent research indicates that, in practice, term limiting legislators often results in legislative behavior that actively diminishes collaboration across the political aisle. In fact, predetermining how long a politician may stay in office increases the likelihood of partisan relationships among legislators—a finding that goes against the assumptions of term limit proponents. We show that in term-limited legislatures, particularly in those with ample resources, members are far less likely to reach across the aisle and participate in bipartisan bill collaboration than those who are not so limited. The fear that bipartisan relationships will harm their future career significantly reduces the possibility of any cross-party alliance.

We believe the dampening effect of term limits on collaboration is not primarily driven by new legislators’ lack of experience or established relationships. Instead, we argue the career uncertainty that term limits induce fundamentally damage the likelihood of bipartisan cooperation. When individuals know their career as a legislator has a defined end date, their decisions become influenced by perceptions of what may help, or harm, their future political career prospects. After all, once term limited legislators get evicted from their current seat, they very frequently compete for offices in the opposing chamber or executive branch.

Why would a legislator reduce her bipartisan behavior? How might that negatively affect a future campaign for political office? Bipartisanship is a risky electoral strategy because it entails a potential punishment by strong partisan voters and future campaign donors. Rather than risk being portrayed as a weak partisan, term-limited legislators prefer to “play it safe” and turn away from collaborative opportunities with the opposing party. By choosing a more partisan route, term-limited legislators are attempting to “package” themselves as strong partisans for the next possible campaign, political appointment, or consulting job.

Our findings are based on bill cosponsorship data for 41 states (82 legislative chambers) compiled by LegiScanâ, a third-party service that scrapes state legislative websites for bill information. We analyzed the propensity of legislators to engage in bipartisan relationships by measuring the proportion of bills receiving support from at least one sponsor in each party. This provides the general proclivity of legislators to cross the aisle when developing or rounding up support for legislation.

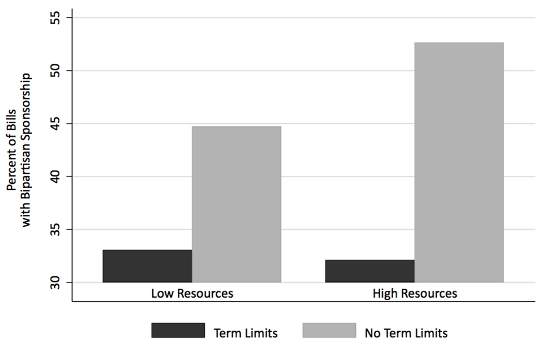

Figure 1 below illustrates the collaborative differences we see in term limited and non-term limited legislatures. It also breaks these data down by the degree of resources provided to the chamber’s membership. The graph depicts stark differences between term limited and non-term limited legislatures. While over 50 percent of bills receive some form of bipartisan support in high resource, non-term limited legislatures, only a little more than 30 percent of bills do in term-limited states. In these high resource environments, public office appears more desirable and therefore we see stronger effects from term limits in these states. We observe a less pronounced decrease as a result of term limits among the low resource states.

Figure 1 – State Bipartisan Bill Collaboration by Term Limited Status and Legislator Resources

This behavior has not gone unrecognized. In Florida, a term-limited state, legislators have expressed frustration over their membership’s behavior, and journalists comment “members are more self-interested and focus on projects that will benefit their personal political ambitions, rather than consider the long-term policy implications for the state”. Similarly, the Sacramento Bee’s editorial board recently pleaded with members of the California Assembly to “not use their office as a resume builder for a lucrative consulting career”.

The policy implications of these findings for term-limited legislatures are stark, particularly in an era of seemingly ever increasing partisan polarization. The noble goal of electing a more civic-minded legislature with the public’s best interests at heart does not appear readily achievable under term limits, contrary to reformers expectations. Term limits have made legislating less about policymaking and more of an exercise in political ambition, only serving to exacerbate the same concerns that led to their original implementation.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Term Limits and Collaboration Across the Aisle: An Analysis of Bipartisan Cosponsorship in Term Limited and Non-Term Limited State Legislatures’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Justin Norman (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Pb08pt

_________________________________

Clint S. Swift – University of Missouri

Clint S. Swift – University of Missouri

Clint S. Swift is a Ph.D. candidate and former J.G. Heinberg Scholarship recipient at the University of Missouri. His research interests include state legislative institutions and behavior, electoral accountability and elections. His dissertation focuses on the determinants of state legislative committee system structure as well as its effects on legislative outcomes.

Kathryn VanderMolen – University of Missouri

Kathryn VanderMolen – University of Missouri

Kathryn VanderMolen is a Ph.D. candidate and Kinder dissertation fellow at the University of Missouri. Her research interests focus on questions of institutional design and representation in the American states. She will be joining the University of Tampa as an assistant professor of political science in Fall 2016.

1)your graph is misleading

2)is the 50vs30% difference statistically significant?