The Constitution is widely interpreted to separate the church from the state in the US, but religious and political attitudes are often closely related. In new research Amanda Friesen and Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz examine how the intersection of religion and politics influences people’s worldviews and how this in turn is influenced by genetics. Using a twin study, they find that the importance of religion in people’s minds is positively linked with conservative views on social issues, and that much of this relationship is due to genetics, though environmental factors are also important.

The Constitution is widely interpreted to separate the church from the state in the US, but religious and political attitudes are often closely related. In new research Amanda Friesen and Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz examine how the intersection of religion and politics influences people’s worldviews and how this in turn is influenced by genetics. Using a twin study, they find that the importance of religion in people’s minds is positively linked with conservative views on social issues, and that much of this relationship is due to genetics, though environmental factors are also important.

The intersection of religion and politics in the United States seems commonplace to Americans, even if it puzzles many of our democratic peers abroad. Traditionally, scholars have examined this connection by treating the religious and the political as two separate but related belief systems – institutionally, across society, and within individuals — that influence one another through socialization, group identity, belief structures, elite messaging, and so on.

In new research, we challenge this view and suggest that religion and politics intersect in certain contexts because both worldviews reflect an underlying disposition toward how individuals understand and wish to organize society. For example, if an individual views morality in concrete, black-and-white terms and wishes to punish rule breakers accordingly, he or she will be drawn to ideologies that satisfy or fit with this type of orientation, whether religious, political, or possibly both. Our research pushes this line of thinking further and suggests that this orientation may be partially due to genetics. Other scholars have established that religious, political, and other social beliefs and behaviors are influenced by genes and the environment; we examine these belief systems simultaneously and find the existence of genetic and environmental factors that link political and religious orientations, indicating that a common predisposition may contribute to the development of political and religious orientations.

Using a classic twin design on a sample of American adults [Data can be accessed here], we are able to examine the extent to which variation in political and religious orientations is due to genetic and different types of environmental factors, concluding that the source of the shared relationship between the political and the religious is quite dependent on the measure at hand (e.g. church attendance has limited heritability). That is, some political and religious relationships are more due to genetics, some to the environment, and nearly all are influenced by both to some degree.

Classic twin designs – which include both identical and fraternal twins — focus on population variance, rather than population means, in order to divide how twins vary together on a given trait into genetic, shared environmental, and unique environmental components. The genetic component explains how much of the similarities between individuals on a specific trait are due to heritable predispositions. The shared environment accounts for the portion of similarity that stems from twins being raised within the same families and reflects all of the influences in their environment that they have in common. The unique or unshared environment refers to any experience that is not shared between the twins, whether it is differences realized during childhood or as adults.

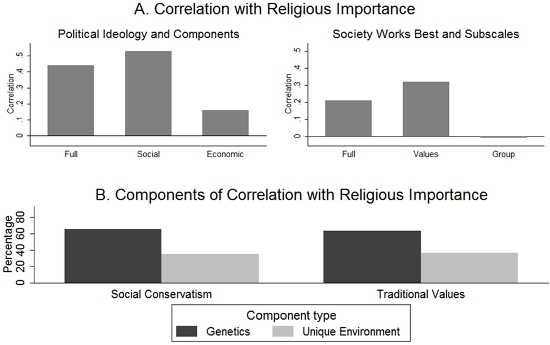

In our twin sample, we find that religious salience (a common measure that describes the importance of religion in an individual’s decision making) – is positively correlated with conservative views on specific social issues (e.g. women’s equality, gay marriage, abortion rights) as well as general views on how society should be organized (e.g. “Society works best when established ideas are favored”). Much of this relationship is due to genetics, though the unique environment is also important. Also noteworthy is that the relationship of religious salience is weak to nonexistent with attitudes on economic issues (e.g. taxes, business regulation).

Figure 1 – Correlation of religious importance with genetic and environmental factors

Nearly 40 percent of the total genetic variance in social issue attitudes in our sample is shared with religious importance; by contrast, less than 20 percent of the total unique environmental variance in social ideology is shared with religious importance. Second, we discover that the majority (87.2 percent) of the variance in religious importance is unshared with the political variables, indicating that there is still much of the religious that is not explained by orientations toward general social order or political attitudes. Our focus on genetic pathways should not detract from the consideration of environmental factors. In fact, one of the benefits of utilizing a classical twin design is that it provides insight into the environmental factors that contribute to variance as much as it does to genetic factors. Our results indicate that social ideology, religious importance, and social order values also share a common unique environmental factor. This suggests that there are some environmental influences or experiences that cause these variables to vary together.

An alternative explanation to our study may be that individuals interpret our key variables as one and the same (i.e. saying religion is an important guide in one’s life and agreeing that “Society works best when people live according to traditional values”). But this is precisely our point. The “society works best” questionnaire (see the Minnesota Twins Political Survey Codebook http://www.unl.edu/polphyslab/data) does not prime respondents for religion and, with its set up, seeks to ask respondents to not think of how “I work best” or “how I want to live my life,” but rather how communities should function. The conflation of religious and political beliefs may be due to political and religious phenotypes representing the same latent trait or individuals calling upon their religious rather than political beliefs to answer both questions.

For example, many Americans self-identify as “conservative,” yet will support policies like raising the minimum wage – leading to “conflicted” conservatism. When individuals in our sample think about organizing society around moral values, they seem to be drawing upon a predisposition that also encompasses relying on religious belief in day-to-day decision making. This partially heritable religious orientation does not explain their economic policy preferences or their group attitudes, but may offer a strong enough identity that causes them to claim a conservative label, even if some of their issue attitudes are progressive.

Future research should seek to generalize our findings by replicating them in more diverse samples and with multi-item measures of religiosity. The nature of the sample (middle aged, largely white, largely Midwestern) leaves open questions regarding whether the link between religiosity, values, and political ideology is conditional on generational differences, age, racial and class dynamics, or regional and cross-national factors. Addressing these questions would significantly advance our understanding of the interconnections among these variables and contribute to our understanding of what drives individual political attitudes, how genetic and environmental factors contribute to the formation and shifts in public opinion, and ultimately whether instantiated political-religious predispositions may drive political disagreement and conflict.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Do Political Attitudes and Religiosity Share a Genetic Path?’, in Political Behavior.

Featured image credit: Joshua Rothhaas (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1NpkNp5

_________________________________

Amanda Friesen – Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis

Amanda Friesen – Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis

Amanda Friesen joined the faculty at IUPUI as an Assistant Professor in Political Science and a Faculty Research Fellow with the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture in 2012, after earning her Ph.D. at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her research interests involve the areas of political psychology, political behavior, religion and politics, gender and politics, and behavior genetics. She has published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London-B, Political Behavior, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, Politics & Religion, Social Science Quarterly, and PS: Political Science & Politics.

Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Aleksander Ksiazkiewicz joined the faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign as an Assistant Professor of Political Science in 2015, after earning his Ph.D. at Rice University. His research interests involve political psychology and political behavior, with a focus on genetics, psychophysiology, and implicit cognitive processes. He has published in Political Behavior, Political Psychology, PS: Political Science & Politics, and Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy.