In North America, substance misuse is very common among young people involved with the juvenile justice system, and even more so among American Indian and Canadian First Nations youth. In new research, Kelley J. Sittner examines the relationship between substance use disorder and other mental disorders such as conduct disorder and ADHD among indigenous young people. She finds that the rates of conduct disorder and substance use disorder were almost twice as large among the arrested than non-arrested adolescents, and that those young people with such disorders were three or four times more likely to be arrested than those without.

In North America, substance misuse is very common among young people involved with the juvenile justice system, and even more so among American Indian and Canadian First Nations youth. In new research, Kelley J. Sittner examines the relationship between substance use disorder and other mental disorders such as conduct disorder and ADHD among indigenous young people. She finds that the rates of conduct disorder and substance use disorder were almost twice as large among the arrested than non-arrested adolescents, and that those young people with such disorders were three or four times more likely to be arrested than those without.

In the United States and Canada, mental and substance use disorders are very common among adolescents involved with the juvenile justice systems). According to a 2006 report, about 70 percent of the youth in the juvenile justice systems of three US states met the criteria for a mental or substance use disorder, and there were high rates of young people with two or more disorders. This is true of justice-involved youth in general, regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds.

But prevailing evidence suggests that American Indian and Canadian First Nations youth (hereafter referred to as Indigenous) are at higher risk than white youth for substance use disorders and externalizing disorders, as well as involvement in the juvenile justice systems. These early patterns continue into adulthood. For example, in Canada, Aboriginal people make up 2.7 percent of the general population but 17 percent of the federal prison population, and Aboriginal adults have an incarceration rate six times higher than the national rate.

Although substance use disorders (SUD) are common among justice-involved youth, the influence the disorder itself has on the likelihood of arrest among Indigenous youth is unclear. But it is logical to think substance use may be strongly implicated in arrest for two reasons. First, all substance use, whether it be alcohol, marijuana, or harder drugs, is against the law for individuals under specific ages. Indeed, alcohol- and drug-related offenses account for a large proportion of juvenile arrests overall, and an even larger proportion of Indigenous juvenile arrests. According to 2014 data from the FBI, liquor law violations accounted for about 5 percent of all juvenile arrests in the US, but almost 12 percent of arrests of American Indian or Alaska Native juveniles. Second, substance use disorder (SUD) is usually regarded as the most severe and problematic form of substance use, and tends to have more serious consequences.

Although mental disorders are more common among justice-involved youth, we know next to nothing about the role played by other mental disorders, alone or in combination with SUD, in the risk of arrest for Indigenous youth. In our research, we examined the association between SUD, its comorbidity with other disorders (conduct disorder (CD), depression, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)), and arrest. As mentioned above, SUD rates are higher among arrested adolescents. We included CD because it indicates persistent and repetitive behaviors that are often against the law. ADHD is characterized by impulsivity and low self-control, which increase the chances of a youth engaging in delinquent behavior. Depression was included given the higher rates of depression observed among justice-involved youth. The data come from an eight-year study of Indigenous youth from the northern Midwest in the United States and southern Canada. More details of the study design and the sample are located in the 2014 book Indigenous Adolescent Development.

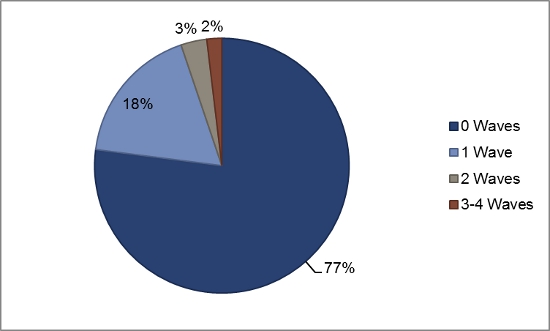

At each wave, we asked the youth in our study whether they had ever been arrested (Wave 1) or were arrested in the past year (Waves 2, 3, and 5). As shown in Figure 1, most of the adolescents reported never being arrested (77 percent). Almost one-fifth (18 percent) reported being arrested once, 3 percent were arrested twice, and a very small proportion (2 percent) reported being arrested three or four times.

Figure 1 – Number of Waves in Which Youth Reported Being Arrested at Least Once (percent)

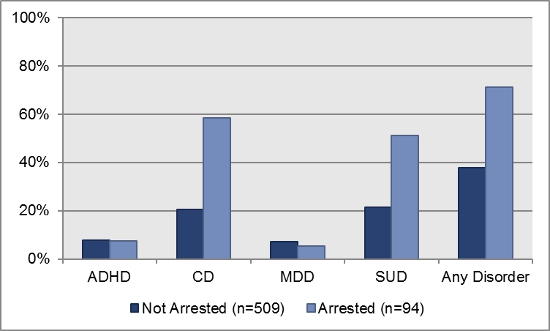

We next compared youth at Wave 5 who reported a past-year arrest to those did not, to determine whether arrested youth had higher rates of mental disorder and SUD. As shown in Figure 2, the rates of conduct disorder (CD) and substance use disorder (SUD) were almost twice as large among the arrested youth, compared to non-arrested adolescents. Arrested youth were also about twice as likely to have met criteria for any disorder. There were near-equal rates of ADHD and Major depressive disorder (MDD) between the two groups.

Figure 2 – Percentage of Youth Meeting Criteria for Mental and Substance Use Disorders, by Arrest Status at Wave 5

Note: ADHD=Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, CD=Conduct disorder, MDD=Major depressive disorder, SUD=Substance use disorder

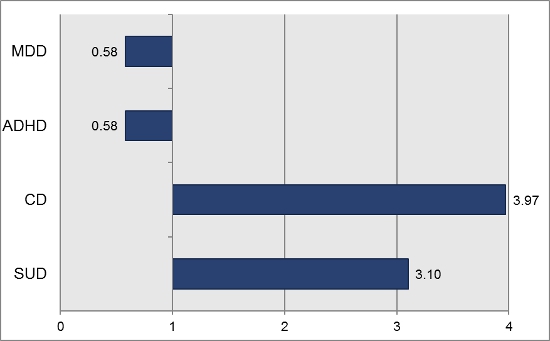

We wanted to see whether the disorders themselves increased the risk of arrest after accounting for other known arrest risk factors. These included adolescent characteristics (i.e., age, gender), family risk factors (i.e., income, parent mental and substance use disorders, parent rejection), and adolescent prior arrest record. Each disorder was analyzed separately, controlling for the risk factors. Figure 3 shows the odds ratios of each disorder predicting arrest in Wave 5 (when the adolescents were 14-16 years old). To help with interpretation, an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates a higher likelihood of arrest. After including the other risk factors for arrest, SUD and CD each were significantly associated with arrest one year later. Specifically, meeting criteria for SUD was associated with a three-fold increase in the odds of being arrested, and meeting CD criteria increased the odds by nearly four times. Neither ADHD nor MDD were statistically associated with arrest.

Figure 3 – Mental and Substance Use Disorders (Wave 4) Predicting Arrest (Wave 5)

Notes: ADHD=Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, CD=Conduct disorder, MDD=Major depressive disorder, SUD=Substance use disorder. Odds ratios for CD and SUD are statistically significant, p<.001.

Although depression and ADHD were not common among the arrested youth and did not work to increase the odds of arrest, we saw a very different picture when those two disorders co-occurred with SUD. Of the seven young people with ADHD who were arrested, six also met criteria for SUD. Similarly, of the five depressed adolescents who were arrested, four met criteria for SUD. This is in line with other research, which finds rates of co-occurring disorders to be very high among arrested and incarcerated youth.

In summary, the youth who come into contact with the criminal justice system have high rates of mental and substance use disorders, a combination that places them at risk for serious, perhaps lifelong consequences. Mental health and substance use problems exert a strong influence on arrest above and beyond other risk factors, which tells us that typical delinquency prevention programs alone are not sufficient to reduce arrest. The key is early identification and treatment of related SUD and mental disorders either prior to or at first contact with the criminal justice system. We need a better response to substance use among Indigenous youth than simply arresting and incarcerating them.

This article is based on the paper ‘Substance Use Disorders, Comorbidity, and Arrest Among Indigenous Adolescents’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Gary Owen (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Sx6SjQ

_________________________________

Kelley Sittner – Oklahoma State University

Kelley Sittner – Oklahoma State University

Kelley Sittner is Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines health disparities among North American Indigenous populations, with a particular focus on delinquency, mental health, and substance use among Indigenous youth. She also studies health, substance use, and mental health of homeless youth and adults.