The US has maintained a military prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba for more than 14 years, with the stated aim of detaining and interrogating suspected terrorists which have been captured by the US. In new research which uses a dataset of information published by WikiLeaks, Emanuel Deutschmann finds that the prison has been largely ineffective in its intelligence-gathering mission. He writes that the dataset shows that nearly two thirds of inmates revealed no information about their fellow detainees, meaning that calls from politicians to send suspected terrorists to Guantánamo Bay to gain information from them are unrealistic.

The US has maintained a military prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba for more than 14 years, with the stated aim of detaining and interrogating suspected terrorists which have been captured by the US. In new research which uses a dataset of information published by WikiLeaks, Emanuel Deutschmann finds that the prison has been largely ineffective in its intelligence-gathering mission. He writes that the dataset shows that nearly two thirds of inmates revealed no information about their fellow detainees, meaning that calls from politicians to send suspected terrorists to Guantánamo Bay to gain information from them are unrealistic.

On February 23, 2016, almost a decade after his first promise to close it, President Obama began a final attempt to shut down the US military prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. His chances of success are moderate, not least since Republican presidential candidates and members of Congress immediately rejected the plan. Florida Senator Marco Rubio for instance stated that: “Not only are we not going to close Guantánamo, when I am president, if we capture a terrorist alive, they […] are going to Guantánamo, and we are going to find out everything they know.”

This idea, compelling as it may sound to some, is unrealistic, as a new study based on leaked Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) documents reveals: although the large majority (85 percent) of Guantánamo detainees was explicitly brought to Cuba “to provide information,” almost two thirds did not reveal any information about fellow detainees whatsoever. Whether this was because they actually did not have any relevant information (which would mean that they were erroneously deported to Cuba) or because they managed to keep silent despite the application of torture (which would mean that the interrogation methods applied by JTF-GTMO were inefficient), one thing is clear: measured by what the US administration expected to learn from its prisoners, intelligence-gathering at Guantánamo was deficient.

Despite the widespread public attention that the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp continues to attract around the globe, there is still little freely accessible knowledge about what is occurring in what is seen by many as one of the world’s most notorious prison camps. This may now change thanks to a new dataset created from JTF-GTMO–authored memoranda on 765 detainees which had been purloined by US Army soldier Bradley Manning in 2010 and published by WikiLeaks. The dataset contains detailed information on almost all prisoners ever held at Guantánamo, including their age, nationality, health status, supposed affiliations with terrorist organizations, intelligence value, disobedient behavior, as well as an assessment whether JTF-GTMO recommends the detainee to be released. Furthermore, the data includes a network of incriminating statements between the detainees, giving us new insights into who the Guantánamo detainees are, how their actions matter, and how they behave in terms of releasing information on each other. On a broader note, it demonstrates what can be gained by using WikiLeaks documents for social science research, which scholars, particularly in the US, have long been reluctant to do in fear of sanctions.

Who the Guantánamo detainees are

Guantánamo brought together people from all over the world. Detainees came from countries as diverse as Canada, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, Great Britain, Spain, Turkey, Russia, China, Bangladesh, Sudan, Uganda, Zambia, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Maldives. The largest national groups however are Afghans (29 percent), Saudi Arabians (17 percent), Yemenis (15 percent), and Pakistanis (9 percent).

Half of all detainees were allegedly associated with Al-Qaeda, 13 percent with the Taliban and 4 percent with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Of the total, 19 percent were assessed to be affiliated with a terrorist organization other than Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. For almost a quarter of all detainees no affiliation with any terrorist organization was mentioned.

For 84 percent of the detainees, the single explicit reason for transfer to Guantánamo was “to provide information.” About 7 percent of the detainees were brought to Guantánamo because of an alleged affiliation with Al-Qaeda or similar incriminating circumstances. In 2 percent of the cases, the reason was an alleged affiliation with Al-Qaeda and the provision of information. Only 12 detainees (less than 2 percent) were transported to Guantánamo “to face prosecution for terrorist activities against the US.”

How the Guantánamo detainees’ statements matter

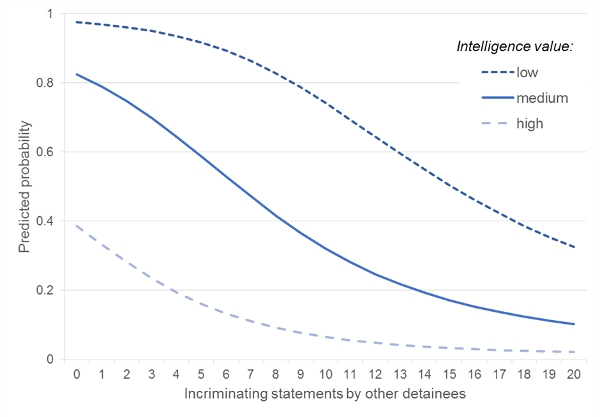

By revealing information, detainees don’t improve their own chances of getting release recommendations but impair those of the detainees they implicate. Figure 1 illustrates, for detainees who are assessed to have a “high,” “medium,” and “low” intelligence value, how the probability of getting a release recommendation decreases as the number of incriminating statements made by others about the detainee increases. For a detainee with medium intelligence value, for example, the probability of getting a release recommendation drops dramatically from 82 percent to 32 percent and further to 10 percent as the number of incriminating statements made about him increases from 0 to 10 to 20. These numbers illustrate that while having no impact on their own chances to get release recommendations, the Guantánamo detainees profoundly influence the fate of others.

Figure 1 – Predicted probability of getting a release recommendation

How the Guantánamo detainees behave

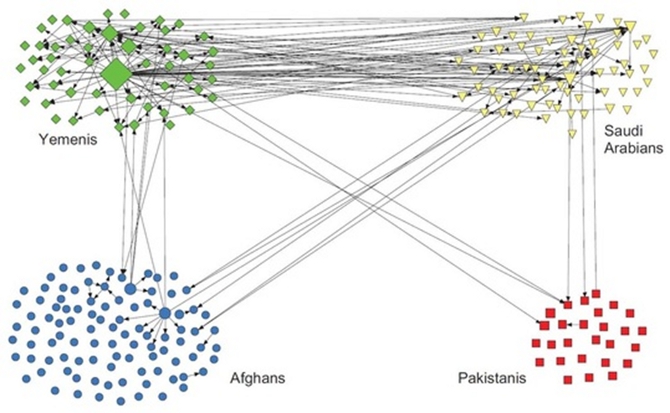

Figure 2 shows a sample network of incriminating statements between detainees from the four largest national groups at Guantánamo. It illustrates that Yemenis and Saudi Arabians make and receive most statements, while most Afghans and Pakistanis don’t talk and are not talked about. Though this does not necessarily mean that they are “innocent,” it strongly suggests that selection and screening problems were detrimental for intelligence-gathering at Guantánamo.

Overall, the web of information gathered at Guantánamo follows a mathematical pattern that can be found in many natural and social phenomena, the so-called power law: a very small number of detainees incriminated a large number of others while a larger group of detainees incriminated only a few others. The large majority of all detainees (63 percent), however, do not reveal any information about fellow inmates at all. Furthermore, the information given by the few high-level collaborators has been assessed to be questionable.

Figure 2 – Incriminations between detainees from the four largest national groups at Guantánamo

In sum, the analysis casts light on the notoriously opaque American prison and reveals, that the amount of information gathered from Guantánamo detainees is low: most prisoners don’t make incriminating statements despite the fact that they were expected to have information and connections to terrorist groups and notwithstanding the fact that US interrogators admittedly used torture to make people talk at Guantánamo. Thus, the current plans of Republican presidential candidates to send new suspected “terrorists” to Guantánamo “to find out everything they know” is unrealistic and misleading. Guantánamo and its selection and interrogation methods have not only cost American taxpayers millions of dollars and seriously harmed America’s moral reputation in the world; they have also proven to be quite ineffective with regards to intelligence-gathering. It is time to finally close Guantánamo down.

This article is based on the author’s paper “Between Collaboration and Disobedience: The Behavior of the Guantánamo Detainees and its Consequences”, in the Journal of Conflict Resolution. For a free version, click here.

The research that this blog post is based on was carried out at the University of Oxford in 2011-12 where it passed through the research ethics clearance procedure of the Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC), which aims at ensuring that “research activities involving human participants are conducted in a way which respects the dignity, rights, and welfare of participants, and which minimizes risk to participants, researchers, third parties, and to the University itself”.

All analyses conducted in the article refer either to the population of detainees at Guantánamo as a whole or to a national (Afghans, Yemenis, etc.) or behavioral (high-level collaborators, non-collaborators, etc.) subgroup, but never to a specific individual. As part of the Journal of Conflict Resolution‘s data access and research transparency policy, the author uploaded the dataset to the journal’s repository which is hosted by SAGE. To protect the dignity, rights, and welfare of the Guantánamo detainees, the data was carefully anonymized before submission, i.e. the detainees’ names as well as their Internment Serial Numbers (ISNs) were deleted. Thus, no conclusions about particular detainees or their actions can be drawn from the article, dataset, or blog post. Hence, no individual was put in any sort of danger by this research.

Featured image credit: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/22moVgu

_________________________________

Emanuel Deutschmann – Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences and Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg

Emanuel Deutschmann – Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences and Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg

Emanuel Deutschmann is an affiliated PhD fellow at the Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences and a research associate at Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg (Germany). His research interests include social networks, transnational activity, and human behavior under conditions of uncertainty. He holds an MSc from Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Great clear article. On wikipedia and other websites there is tons of information about gitmo and black sites. This is horrible not just as an information plainly but as it shows that there is a clear try to cover up information that implicates Pentagon and other players interests that if these ppl they fear are at large risk a lot.

We have information that incriminates pentagon fbi cia sof and many dogs to PMC firms and still we are reflecting on what to do? Make these legal parties go rogue. They are the **** of USA and they show how much republican is an economical organization connected to provate military and non military companies making a mess in USA and abroad … not law aniding and instead banding rules at their own pleasure.

Of course obama presidency could not touch this because of congress, clinton and surely the risk of life of his own family. Here there is a lot at stake. Peace for the World. Reduce the paractice of doing business on human lives.

Great article. Thanks