In the past year, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has illustrated the potential negative impact that state takeovers of local governments can have. Domingo Morel delves into this issue by looking at how state takeovers of school districts in New Jersey have affected how Blacks and Latinos are represented on local school boards. He finds that these takeovers led to increased representation for Latinos – who had lower levels of political empowerment – on school boards, and poorer representation for blacks.

In the past year, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has illustrated the potential negative impact that state takeovers of local governments can have. Domingo Morel delves into this issue by looking at how state takeovers of school districts in New Jersey have affected how Blacks and Latinos are represented on local school boards. He finds that these takeovers led to increased representation for Latinos – who had lower levels of political empowerment – on school boards, and poorer representation for blacks.

The recent water crisis in Flint, Michigan, as well as a recent teacher walk-out in Detroit have brought attention to the role of state governments in local governance. In most US cities, decisions concerning the local water supply and school affairs are made by local governments. However, local residents and their elected officials in Flint and Detroit do not have decision-making authority over their water supply or their local public schools. Flint and Detroit have experienced state takeovers of their local government functions and the imposition of state Emergency Managers.

Despite the widespread attention that Flint and Detroit have gained, we know little about state takeovers of local governments. Furthermore, we know little about the political implications of state takeovers for communities of color; the communities mostly affected by state takeovers.

State takeovers are a relatively recent phenomenon in American politics. The first state takeover of a local school district didn’t occur until 1989. In new research, I argue that state takeovers of local governments are part of state centralization efforts that emerged in the 1970s. A combination of greater state powers and changes in urban politics led states to centralize authority over traditional local government functions.

The scholarship on government centralization and decentralization has generally argued in favor of decentralized arrangements as a way to enhance democratic participation. Indeed, the state of Michigan’s blatant disregard of citizens’ concerns in Flint and Detroit – two majority African American cities –support the argument that state centralization negatively affects communities of color.

Although contemporary studies suggest that centralization is detrimental to communities of color, these arguments ignore the complicated history that racial minorities have had with government. At times, the state has prevented racial minorities from achieving political power; and at other times, it has helped in the process of political empowerment. The centralization puzzle is further complicated when the levels of government in tension involve states versus local governments. Historically, racialized communities have been subjected to discrimination that has been sanctioned and perpetuated by state and local governments. Therefore, as states centralize authority over local governance, what are the political implications for communities of color?

In my study, I examine the effects of centralization on racialized communities by exploring how state takeovers of local school districts affect Black and Latino descriptive representation (where elected representatives represent the characteristics of their constituencies as well as their preferences) on local school boards. Descriptive representation has been one of the key factors that researchers have used to assess a community’s level of political empowerment. The empirical results of the study show that contrary to conventional wisdom, under certain conditions, takeovers and centralization can actually lead to greater descriptive representation and political empowerment among marginalized populations. On the other hand, I also find that under other conditions, takeovers are even more dis-empowering than we previously understood.

My study begins in Newark, New Jersey. In 1967, the city erupted in one of the deadliest urban uprisings in US history. Following the unrest, Governor Richard J. Hughes commissioned a report on “Civil Disorder” in the state. The report cited the absence of Black political empowerment as a major factor that “helped set the stage for the July riot.” The report specifically cited the lack of Black representation on the school board as a significant issue. Although African Americans constituted the majority of the population in Newark by the mid-1960s, as of 1967, there was only 1 African American and no Latinos on the school board. To address the lack of Black representation on the school board, the Commission recommended that the state take over the Newark schools and restructure school governance to provide greater opportunities for the city’s Black community to influence school policy.

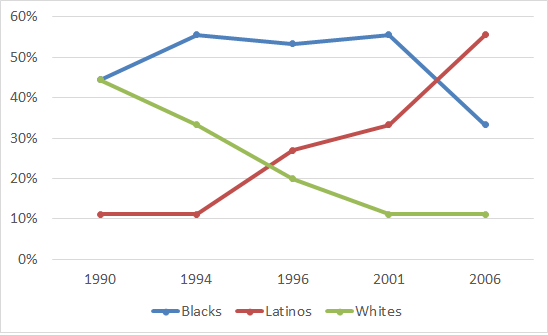

The Black and Latino communities in Newark, who were politically marginalized, did not oppose a state plan to take over the school district because they viewed the proposed intervention as a potential path to political empowerment. Leaders in the Black community, including Kenneth Gibson, who would become the city’s first Black mayor in 1970, supported the plan. Despite the Commission’s recommendation, the state did not take over the Newark schools in 1968. However, the state did take over the Newark schools in 1995. By then, the city’s Black community did have political power and viewed the takeover as a threat to their political empowerment. Latinos, on the other hand, who had low levels of political empowerment at the time of the takeover, did not view the takeover as a threat, and in fact, gained greater representation on the school board as a result of the takeover. Following the takeover, the state appointed a new board which led greater Latino representation on the board. Additionally, the takeover seemed to spur greater interest in school level politics among Latinos in Newark.

Figure 1 – Newark School Board Descriptive Representation 1990-2006

Note: State takeover occurs in 1995

The second part of my study uses the findings from the Newark case to formulate and test hypotheses on how centralization affects Black and Latino descriptive representation on school boards. Relying on an original dataset of the universe of state takeovers of local school districts between 1989 and 2013 the findings show that communities with high levels of political empowerment (measured by Black or Latino descriptive mayoral and city council representation) at the time of centralization, are most negatively affected by takeovers. On the other hand, communities with low levels of political empowerment are not negatively affected by takeovers.

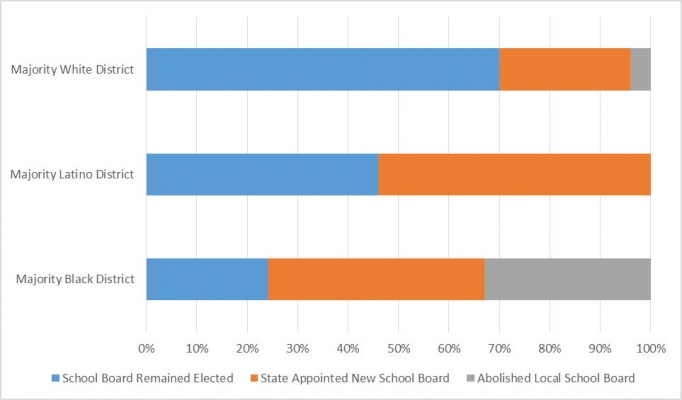

My results show that state governments can assume a role of addressing racial inequities at the local level. However, despite the potential to address political marginalization at the local level state takeovers can have a detrimental effect on local communities; Blacks, the group with the highest levels of political empowerment in communities that experienced state takeovers, were most negatively affected by takeovers. The abolishment of locally elected school boards following a takeover disproportionately affected Black communities. By comparison, although White communities are less likely to experience a state takeover of their local school districts, in cases where majority-White school districts were taken over, the state takeovers did not lead to the political disruption that Black communities experienced.

Figure 2 – School Board Type after State Takeover of Local School District

Centralization can affect communities differently depending on their level of political empowerment at the time of centralization. At the same time, the fact that Black communities have been disproportionately negatively affected by state takeovers of school districts suggests that in addition to examining the effects of state interventions, the logic, justification, and intentions of state centralization merits further examination.

This article is based on the paper “The Effects of Centralized Government Authority on Black and Latino Political Empowerment,” in the journal Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image: New Jersey State House Credit: Patrick Gensel (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QAKqBy

_________________________________________

Domingo Morel – Wellesley College

Domingo Morel – Wellesley College

Domingo Morel is a Visiting Lecturer at Wellesley College. His research examines the effects of state takeovers of local school districts on Black and Latino communities. To learn more about his work visit: www.domingomorel.com. You can also follow him on Twitter @DomingoMorel