While the Great Recession officially ended six years ago, it still has implications for how cities are governed. Sara Hinkley writes that following the financial crisis, many states expanded control over city finances and efforts have been made to reform city’s public sector pensions. She argues that this city-state struggle for control can also be seen as a move to concentrate power by state governments that are more conservative, and that this struggle has made it harder for many cities to fully recover from the downturn.

While the Great Recession officially ended six years ago, it still has implications for how cities are governed. Sara Hinkley writes that following the financial crisis, many states expanded control over city finances and efforts have been made to reform city’s public sector pensions. She argues that this city-state struggle for control can also be seen as a move to concentrate power by state governments that are more conservative, and that this struggle has made it harder for many cities to fully recover from the downturn.

The Great Recession officially ended in the United States in 2009, but the implications for city governments continue to unfold. Austerity measures implemented by cities well into 2013 left a legacy of service reductions and a backlog of infrastructure needs, a lurking national liability that has drawn attention to cities’ precarious fiscal situation.

The long-term effects of the recession on city governance have been particularly severe. Two policy responses in particular—expanded state control over city finances and efforts to “reform” public pension systems—have reverberated well beyond the initial impacts of the recession. In my study of US city responses to fiscal crisis, I found that these two themes persisted in widely different fiscal and economic circumstances. I don’t think we learn much by simply attributing the persistent focus on pensions to a widespread and ongoing neoliberal push for austerity. If we pay close attention to the financial and intergovernmental politics involved, we see that each city reveals something specific about the ongoing problematic of municipal fiscal power in a framework of federalism.

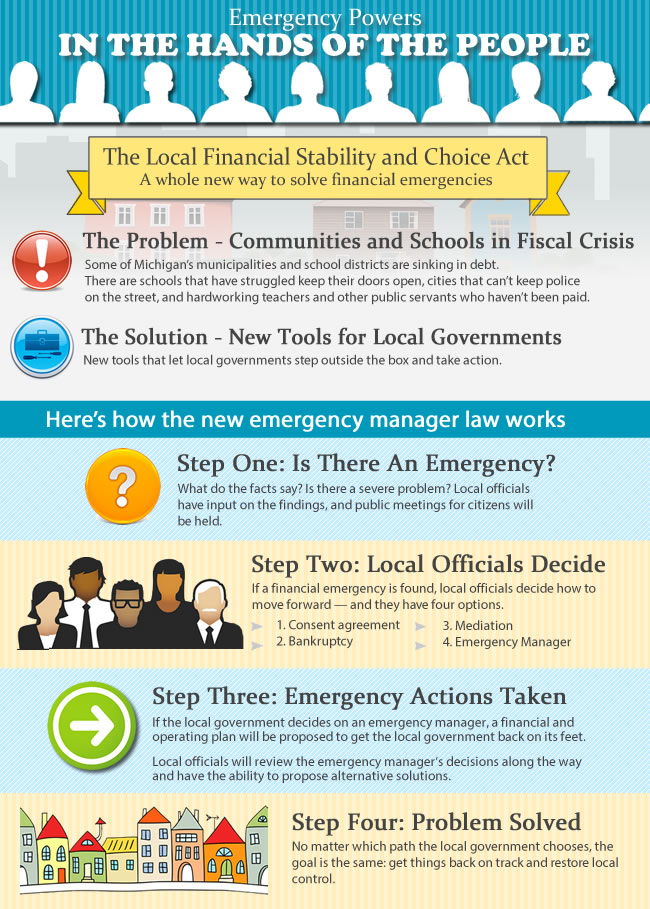

Fiscal crises in the US constitute histories of negotiation between city and state power, with states claiming additional oversight powers of city governance in each crisis (Sbragia’s Debt Wish presents a great history of this process). The dramatic revelation in 2015 that residents of Flint, Michigan, had been drinking lead-contaminated water for several months brought unusual scrutiny to such powers, in the form of Michigan’s emergency manager law, under which an appointed executive switched Flint’s water source to save money.

Michigan’s emergency manager law is the most far-reaching in the country; even before Detroit was taken over by an emergency manager (to the acclaim of credit ratings agencies), five cities and three school districts (including Flint) had been taken over. In late 2012, just months before Detroit’s bankruptcy, Michigan voters had repealed the emergency manager law by popular referendum, only to have a nearly identical version quickly passed by the state’s Republican legislature. Despite widespread critique in the wake of Flint’s disaster, the law remains in place.

The erosion of local democracy and fiscal autonomy at the hands of state governments in the US has been one ongoing consequence of the Great Recession. State governments in the US already exert significant control over city finances: they regulate access to municipal credit, control cities’ ability to raise revenues, and define the options for responding to economic downturns (including access to bankruptcy or state receivership). Since 2007, states have broadened powers of fiscal monitoring (North Carolina, New York), emergency takeover (Michigan, Rhode Island), and control over municipal bankruptcy (Pennsylvania, California).

The justification given by state legislatures for this increased control is twofold: that city governments lack the political will to make necessary cuts, and that city fiscal distress can be contagious. Expanded state powers have been praised by financial ratings agencies, who are especially keen on keeping cities out of federal bankruptcy, where a judge may value the claims of pensioners over those of bondholders and other creditors (as happened in Detroit).

This city-state struggle for autonomy and control can also be seen as a move to concentrate power by state governments that are more politically and socially conservative, more (and perhaps disproportionately) influenced by rural and suburban political interests. The combination of this move for state intervention and the ongoing project of federal devolution has, by and large, left American cities to falter in the face of economic downturns. Blame for that faltering has been displaced, in recent years, onto the shoulders of public employees.

The second legacy of the recession has been a national consensus that public pension plans have dragged down city and state budgets below the point of sustainability. Public pension reforms have been largely framed as a victimless policy shift that simply aligns public workers’ benefits with their private counterparts, and as a long-overdue correction to excessive commitments made by local governments to public workers. Financial analysts have described the structural threat posed by pension and health care costs as “unsustainable” and “ridiculous” (see Chappatta’s numerous articles). The funds have been described as chronically underfunded, threatening to hobble cities and states if measures are not taken to cut benefits.

The narrative of a national public pension crisis is simplistic on (at least) two counts. First: the “health” of any pension plan is based on many moving pieces: the projected rate of return on plan assets, the value of the assets at a given moment in time, and estimates of future liability (i.e. pension payments). During the financial crisis, these pieces were significantly reshaped.

In November 2008, Moody’s reported that retirement systems’ stock investments had fallen by 35 percent. Rates of return that seemed reasonable in 2007 (and which were widely used by the private sector) were cut significantly (ratings agencies and cities continue to differ in the rates of return used to estimate future assets). These market declines escalated a key measure of pension plan health: unfunded actuarial accrued liability (UAAL). Because the actuarial required contribution (ARC), which cities must pay from operating expenses, is based in part on estimations of future returns, cities abruptly faced a significant operational cost increase, just as their revenues contracted.

Some plans went into the recession already underfunded, in part because of how city pension funding fits into a strategy of fiscal mitigation that reflects the instability of city fiscal structures. In some cases, cities’ discretion over how much of the ARC must be paid out of the operating budget each year represents a significant share of the discretion available in the budget. Both the formula for calculating a city’s ARC and the degree to which it must comply with that calculation are subject to local and state policies.

In 2011, the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB), followed in short order by all three major credit ratings agencies, began to account for government pension liabilities as equivalent to debt; Moody’s and the other ratings agencies took the additional step of increasing the weight given to debt in a government’s overall rating evaluation. Thus the emergence of a pension “crisis” has been a product of both the politics of city fiscal management and its monitoring.

As pressure from state officials and creditors pushes cities to focus on restructuring pension plans as a short-term fix for operating deficits, there has been little conversation about how cities can increase long-term stability before the next economic crisis erupts. While something must be done to shore up public pension plans (whose beneficiaries often can’t fall back on social security), we shouldn’t kid ourselves that this debate is moving cities toward fiscal sustainability.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Structurally adjusting: Narratives of fiscal crisis in four US cities’ in Urban Studies.

Featured image credit: Ann Millspaugh (Creative Commons: BY-SA 2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1UP5iw0

_________________________________

Sara Hinkley – UC Berkeley

Sara Hinkley – UC Berkeley

Sara Hinkley is a Lecturer in City & Regional Planning at UC Berkeley and a Postdoctoral Scholar at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. Her research interests include the growing complexity of municipal finance, the relationship between public finance and social and racial inequality, and the politics of local economic development. She is also developing a project examining the politics of urban education finance in California. At Berkeley, Sara has worked on research projects at the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, the Goldman School of Public Policy, and the Center for Community Innovation.

“The funds have been described as chronically underfunded, threatening to hobble cities and states if measures are not taken to cut benefits.”

Well, how would you describe them? Here’s some help: A link to Detroit Public Schools Financials 2015 Annual Report: http://detroit.k12.mi.us/data/finance/docs/2014-2015_CAFR.pdf Detroit spends over $17,000 a year per student. And still owes over $1 billion in unfunded pension liabilities a 7% rate of return. DPS is separate from the city, so they still have a very good chance to enjoy the fruits of bankruptcy.

As ugly as the Emergency Manager law is (and I agree with it’s various criticisms), it was used because the core problem(s), and the other alternatives looked worse. These cities have serious problems made worse by incompetent and corrupt local officials, the rest of the state has had it with bailing them out so no blank checks. For example Detroit’s schools get more (not less) money per pupil than most Michigan areas (average is $12.5k, they get $14k, our own local area is $9k and we moved here for the schools).

IMHO, no one really knows what to do. If the emergency manager didn’t work, then would an ugly bankruptcy in the future have been better? Detroit’s pension holders could have gotten a much larger ‘haircut’, leaving the locals in charge seems intuitively like a good way to result in that. Similarly the schools are bad enough that maybe we just let them fail and hope enough charters become available that it works out.