For decades broken windows – the theory that tackling small nuisances will reduce the risk of more serious crime – has dominated policing in America. But new thinking about policing instead uses an approach which focuses resources on the small number of people who drive street violence. Michael Sierra-Arevalo and researchers at Yale University analyze one such initiative – Project Longevity – in New Haven, Connecticut. They find that the program can be linked to a significant reduction in the monthly number of group member shootings and homicides.

For decades broken windows – the theory that tackling small nuisances will reduce the risk of more serious crime – has dominated policing in America. But new thinking about policing instead uses an approach which focuses resources on the small number of people who drive street violence. Michael Sierra-Arevalo and researchers at Yale University analyze one such initiative – Project Longevity – in New Haven, Connecticut. They find that the program can be linked to a significant reduction in the monthly number of group member shootings and homicides.

Police folklore championed by NYPD Commissioner William Bratton Jr. holds that if you “Take care of the little things, then you can prevent a lot of the big things.” However, a recent report suggests that these claims are unfounded—arresting turnstile jumpers and stopping, questioning, and frisking millions of innocent citizens has no effect on serious crimes like shootings or homicides.

Instead, cities like New Haven, Connecticut, have had success in addressing gun homicide by doing something very different from police sweeps and broadly-applied police stops: concentrating police, social service, and community resources on the small number of individuals that drive shootings and homicides in American cities.

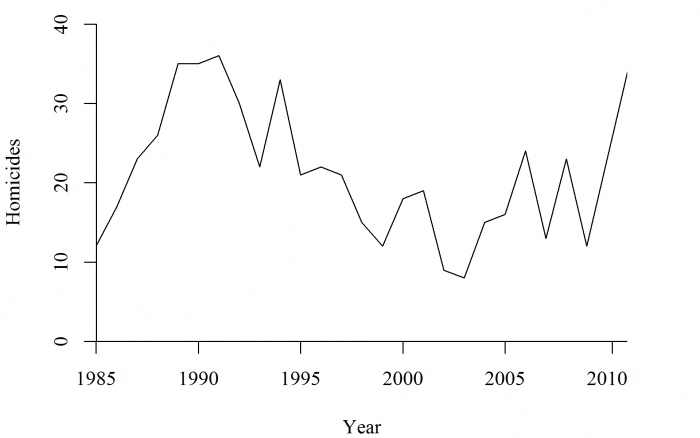

In 2011, New Haven’s 34 homicides nearly matched its 1991 record of 36, placing the home of Yale University on an even-footing with Oakland, California, and outstripping the homicide rate of Washington, D.C.

Figure 1 – Homicides in New Haven, CT (1985-2011)

In response, the State of Connecticut implemented Project Longevity, a focused deterrence strategy based on the pioneering work of David Kennedy in Boston. This approach—a move away from the sweeps and stops associated with “broken-windows” policing made (in)famous by Los Angeles and New York City—is based on focusing attention and resources on the small number of individuals that drive street violence.

As Kennedy and his colleagues found in Boston, the overwhelming majority of gun homicides in urban areas are committed by an exceedingly small section of the population: most shooters are young, minority males, often involved in street groups like drug crews or gangs.

With New Haven as a pilot site, Project Longevity coordinated the experience, expertise, and resources of law enforcement, social service providers, and community members to combat gun violence. Instead of sweeping through communities to stop, search, and question, Longevity focused on those identified by law enforcement in group or gang audits as being involved in violent street groups. Once identified, the partnership used call-ins—meetings between the project partnership and members of violent street groups—to disseminate a simple message: the gun violence must stop, there are social services for those who are willing to put the guns down, and there will be consequences for those who don’t.

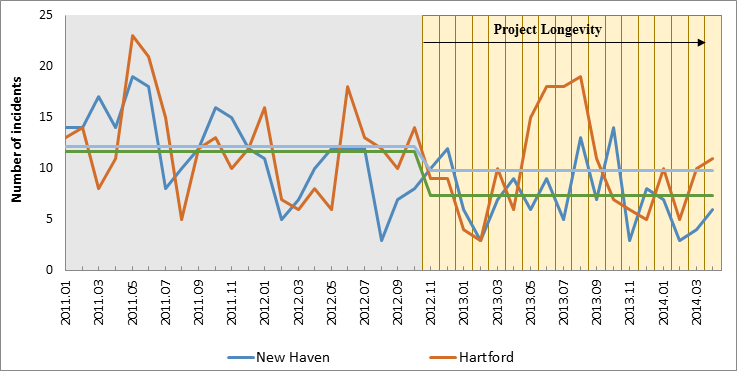

The effect of this seemingly simple approach speaks for itself. A recent analysis of the effect of Project Longevity in New Haven by myself and my colleagues shows that Longevity is associated with a reduction of nearly 5 group member involved (GMI) shootings and homicides per month in New Haven.

Figure 2 – Monthly distribution of the shootings and homicides in New Haven and in Hartford before and during Project Longevity

Importantly, we also account for a variety of potential counter-explanations for the effects shown. First, we demonstrate that what happened in New Haven is independent of any changes in gun violence in Hartford, CT, a city less than an hour north of New Haven. That is, we show that the reduction in GMI shootings and homicides did not happen in a similar city that did not have Longevity actively operating.

Additionally, our analysis checks whether or not the reduction in group member involved shootings is rooted in a broader decrease in group criminality. Using police arrest records that show two or more co-offenders for a given arrest, we show that while co-offenses increased over the course of our observations, the number of GMI shootings and homicides decreased. This suggests that the reduction in group member involved shootings is unrelated to general patterns in group crime.

All told, the results in New Haven are consistent with past assessments of focused deterrence programs in cities across the country; from major metropolitan areas like Los Angeles and Chicago, to smaller cities like Rockford, IL and High Point, NC, initiatives like Longevity have been effective in reducing the gun violence that has plagued inner-city communities for decades.

Importantly, Longevity is not a police-only venture—it is through cooperation between law enforcement, social service providers, and community members that street violence is addressed. By providing street group members with a choice and by being transparent with them and the community about the consequences that await further acts of violence, this kind of intervention has the potential to improve police legitimacy in communities that have long distrusted police.

As we increasingly recognize that locking up more people does not mean safer streets, Longevity and other focused deterrence programs stand as exemplars for a new way forward. Gun violence on American streets is an unfortunate reality, and arrests are inevitable. However, by narrowing focus to address those who are most likely to be victims and perpetrators of street violence, initiatives like Longevity can save lives by not only reducing violence, but also minimizing the number of individuals caught up in the criminal justice system.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Evaluating the Effect of Project Longevity on Group-Involved Shootings and Homicides in New Haven, Connecticut’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Kris (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/29MP0QK

_________________________________

Michael Sierra-Arevalo – Yale University

Michael Sierra-Arevalo – Yale University

Michael Sierra-Arevalo is a PhD candidate at Yale University. His dissertation research focuses on the relationships between police and the public, particularly how police perceptions of danger influence police behaviors. His research interests also include gangs, gun violence, social networks, and public policy strategies for reducing urban violence. Since 2012, Sierra-Arevalo has provided research and programmatic support to Project Longevity, a statewide gun-violence prevention program being implemented with cooperation from local police, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, social service providers, and the local community.

Congratulations on your successful work. I have the highest regard for David Kennedy’s work and thinking. If it is more effective than broken windows in dealing with violence, great! Another valuable tool. I wonder why, however, you had to contrast it with broken windows. To get more publicity? Or were you unfamiliar with the broken windows literature? If you haven’t seen the July 2015 issue of the Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency, especially the work of Anthony Braga, I would suggest you check it out.

I assume you are a Ph.D. student. Good luck on your dissertation.

George Kelling