Since 2009, 62 percent of President Obama’s Federal trial court judge selections have been racial and ethnic minorities and/or females; he now holds the record for having the highest percentage of female and racial minority trial judges appointed by a US president. But do these new judges work to represent female and racial minority causes? In new research which studies employment discrimination cases filed in the federal courts, Christina L. Boyd finds that female judges are about 15 percent more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff than male judges, and that black judges are 39 percent more likely than white judges to rule in favor of the plaintiff in race discrimination decisions.

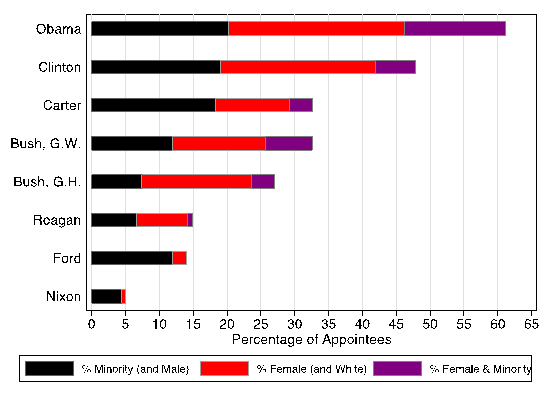

Since taking office in 2009, President Obama has successfully appointed over 90 racial and ethnic minority and 100 female judges to the federal trial courts (“US district courts”). Appointed to life tenure positions under Article III of the Constitution, these newly selected judges make up over 62 percent of Obama’s trial court selections. For comparative perspective, Figure 1 depicts the breakdown of diverse judicial appointments from President Nixon through President Obama. Obama’s record stands out for having the highest percentage of female and racial minority trial judges appointed by a US president.

Figure 1 – Diversity Characteristics of Confirmed Federal District Court Judges

Note: Data compiled from the Federal Judicial Center’s Biographical Directory of Federal Judges.

The Obama Administration argues that these new judges serve as descriptive representatives of diverse communities, producing a judiciary that “resembles our nation,” instills “confidence in our justice system,” and creates “role models for generations of lawyers to come.” But will these diverse trial judges also behave differently on the bench – as substantive representatives for female and racial minority causes – from their white and male judicial colleagues?

To study this, I examine the behavior of federal district judges deciding sex and race employment discrimination cases filed in the federal courts by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) from 1997 to 2006. The data for this project come from the EEOC Litigation Project. Rather than focusing on the final case winner in this matters, which in trial courts can be decided by a judge, jury, or the parties themselves (via a compromised settlement), I instead look at trial judges’ decisions on motions like those to dismiss and motions for summary judgment. Most non-criminal trial court cases develop through motions practice, with the judge’s decision to grant or deny a party’s motion having critical implications for how the case will proceed.

As a recent example of a district court dispositive motion, in the ongoing class-action lawsuit accusing Donald Trump and Trump University of defrauding students, US District Judge Gonzalo Curiel denied Donald Trump’s motion for summary judgment. Had Trump’s motion been granted in full, the case would have ended as a Trump victory. With the motion denied, the case continues toward trial.

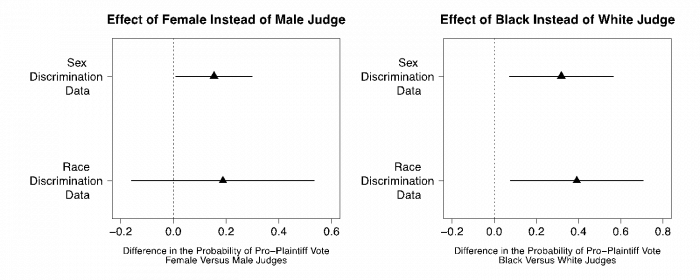

After accounting for other relevant judicial, case, and legal factors that might affect judicial decision making, statistical analysis reveals that the gender and race of a trial judge frequently affects whether there is a pro-plaintiff outcome in employment discrimination-related motions. The left side of Figure 2 displays the results for judge gender. As it reveals, female judges are approximately 0.15 – or 15 percent – more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff than male judges when deciding sex discrimination motions. However, as indicated by the large horizontal confidence interval overlapping 0 in Figure 2’s left panel, there is no difference between male and female trial judges when deciding race discrimination motions.

Figure 2 – Judge Gender and Race Effects on the Probability of a Pro-Plaintiff Ruling

Figure 2’s right panel indicates that judge race has an even stronger effect on motion outcomes. Indeed, as the figure shows, black judges are 39 percent more likely than white judges to rule in favor of the plaintiff in race discrimination motion decisions and 32 percent more likely than white judges to rule in favor of the plaintiff when deciding sex discrimination motions.

Together, these results indicate that even though all trial judges – white, minority, male, and female – undergo the same professionalization, socialization, and training before joining the bench, they do not all make the same decisions. Rather, we see a significant amount of diversity-based substantive representation. Female judges are more likely than male judges to rule in favor of litigants who believe they were discriminated against in the workplace because of their sex. Black judges are more likely than white judges to rule in favor of plaintiffs who were discriminated at work based on their race or their sex.

These findings have important implications for the federal judiciary. Federal district courts now decide nearly 400,000 cases a year. This far exceeds those decided by US Courts of Appeals (<60,000 cases) and the US Supreme Court (~80 cases). With an ever-growing number of diverse judges on the federal bench thanks to President Obama’s appointments, there will almost certainly be an impact on the resulting policy and law that will affect a tremendous number of people and cases.

This article is based on the paper “Representation on the Courts? The Effects of Trial Judges’ Sex and Race” published in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Shawn Calhoun (CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ca9OXn

_________________________________

Christina L. Boyd – University of Georgia

Christina L. Boyd is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Georgia and a lawyer. Her research focuses on the empirical examination of judges and litigants in federal courts. Her scholarship has been published in journals such as American Journal of Political Science, Political Research Quarterly, and Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization and has been funded by the National Science Foundation.

Judges making rulings based on the skin colour of the parties involved (instead of the merits of the case) shows that the justice system is in fact not colour-blind and not impartial (thus it arguably is a fraud, as Federal Judges are supposed to be neutral, and as such, they get life-terms on the bench). Such characteristics of partiality of a Judge or Justice should be cause for sanction or even removal of that individual. This article should not be proud of these results, as it leaves the reader of this article wondering if skin colour is really all that matters in the judicial system.