During the course of the 2016 presidential election, the topic of candidate temperament and fitness for office has been widely discussed. Adam J. Ramey, Jonathan D. Klingler, and Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. show how their personality traits can be estimated from their speech, and what these estimates imply for how they might govern from the White House: Clinton is likely to push substantive policies and back them up, while Trump would push for bolder and more costly proposals, without as much follow-through.

During the course of the 2016 presidential election, the topic of candidate temperament and fitness for office has been widely discussed. Adam J. Ramey, Jonathan D. Klingler, and Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. show how their personality traits can be estimated from their speech, and what these estimates imply for how they might govern from the White House: Clinton is likely to push substantive policies and back them up, while Trump would push for bolder and more costly proposals, without as much follow-through.

The race for the 2016 presidential election is nearing its end, and it has certainly been notable. Both major party candidates are historically unpopular, and both represent very different visions for America. Donald J. Trump, the Republican nominee, proposes stark changes in American foreign and domestic policy, whereas the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, proposes more incremental ones. However, beyond their stark differences in policy proposals are major differences in personal styles, much of which has received considerable coverage in major media outlets. While the Republican nominee is often characterized as bombastic and narcissistic, the Democratic nominee is often characterized as cold, aloof, and calculating.

While these characterizations make for entertaining reading, and may (or may not) explain why some individuals might vote for one instead of the other. However, as structured, they do not provide much insight into how we can expect either of them to govern as President (though discussions of the importance of “temperament” suggest that the demand is there). That said, it is possible to infer the personalities of the major party candidates, and it is further possible to project how these personality traits might translate into governing styles.

In our new research, we provide a method for estimating Big Five personality traits—Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Emotional Stability (the last of which is sometimes reverse-coded as Neuroticism)—from spoken words. While not universally accepted within the psychological literature, this five-factor model provides a nice cogent summary of the individual differences between individuals. Moreover, in our forthcoming book, More Than a Feeling: Personality, Polarization and the Transformation of the US Congress, we build off work in experimental economics and neuropsychology to show how these five traits can be incorporated into models (both formal and informal) of American institutions. In short, we find that Clinton’s personality traits predict that she is more likely to support substantive or incremental policy initiatives as president, and put the work needed behind them so that they become law, while Trump on the other hand is more likely to support bolder and more costly proposals, but not follow up with their implementation.

Over the course of our book, we define “core cognitive constraints” for each personality trait, which we modify in turn as parameters that can readily be incorporated into models of institutions, but also captures the essence of each trait as characterized by the psychology literature. Within our framework, Openness is effectively modeled as a form of risk preference, Conscientiousness as the extent to which one focuses on long-term payoffs, Extraversion as the weight one places on potential rewards, Agreeableness as the extent to which one’s utility is dependent on the utility of others (and in the course of our book we find that Agreeableness seems to be most closely related to the extent to which one weights the preferences of others from the same party relative to one’s own preferences), and Emotional Stability as the weight one places on potential negative outcomes. While these parameters are slightly different than the Big Five’s traditional formulations in the psychology literature, they are modified in this way to make their incorporation into models of institutions much more tractable.

After developing this theory, we generate hypotheses for how personality traits should affect legislative behavior, testing (and generally finding support for) them using personality estimates derived from speech. Our method builds off a rich literature in personality psychology that suggests one’s speech patterns are reflective of one’s personality; more particularly, it is the structure of one’s speech—as opposed to its content—that reflects personality traits. Leveraging this, we implement cutting-edge machine learning methods to estimate personality traits from speech. In our book, we use the Congressional Record over the last twenty years as our source of speech. We then test our hypotheses using these personality estimates and generally find support for our underlying theory.

We can do the same thing with the two major party candidates to see how we might expect them to govern if they were to be elected President. We collected transcripts from the three general election debates (we limit our analyses to these because they ensure that both candidates are talking about the same topics, which limits unnecessary variation) and estimated personality traits from them.

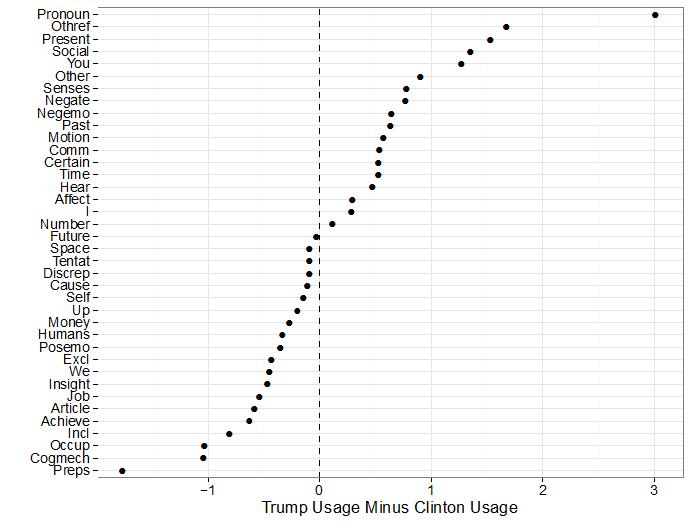

After collecting the transcripts, the first step is to run them through the 2001 version of Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), which strips the language of its meaning and breaks it down into counts of “linguistic features,” such as the number of first-person pronouns, number of future-tense words, and so on. Below, we plot the differences in usage proportions for each candidate.

Figure 1 – Linguistic features of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s speeches

As we can see, the two candidates have very different speaking styles. Trump is much more likely to use negative emotion words (such as “nasty”), and Clinton is more likely to use words that indicate positive emotions (such as “love”); Trump is much more likely to discuss things in the past tense, whereas Clinton is slightly more likely to discuss things in the future tense, and so on.

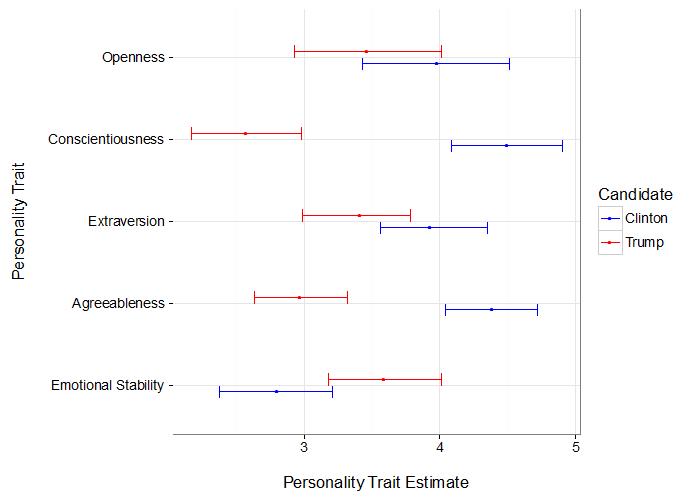

After processing the transcripts through LIWC and recovering the underlying linguistic features, we run a further analysis to generate personality traits for both candidates. The traits are presented below, along with 90% confidence intervals.

Figure 2 – Personality traits for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump based on analysis of their speeches

As can be seen, Clinton and Trump are relatively similar on two dimensions (Openness and Extraversion), and quite different on the three others. As presidential candidates, it should be unsurprising that both are relatively similar on the Openness and Extraversion dimensions, since running for president is an inherently risky proposition, though it carries with it the possibility of great rewards if successful. With this in mind, we focus on the other three traits, which (collectively) reveal much about how they might govern.

That Clinton is much more Conscientious suggests, at least according to our framework, that she is much more likely to take actions resulting in payoffs not received until much later. In our book, we find that legislators who are more Conscientious are more effective, as they are more willing to put forth the long-term effort required to shepherd complex bills through the legislative process; less Conscientious legislators are more likely to sponsor ceremonial bills such as renaming post offices. This finding suggests that Clinton is more likely to invest the effort required to ensure that her substantive policy proposals become law.

Clinton’s higher levels of Agreeableness suggest that she garners more utility from that of others. In our book, we consistently find that the reference group for “others” is likely to be other members of one’s party; this suggests that Clinton is likely to place much more weight on the preferences of other Democrats, whereas Trump is much less likely to consider what benefits his fellow Republicans.

Finally, Clinton’s lower levels of Emotional Stability suggests that she pays extremely close attention to the possible negative outcomes from her actions. Because of this, she is likely to promote policy proposals that are more broadly acceptable (to minimize the potential for political blowback) as well as more incremental in nature (since small changes to the status quo inherently engender lower potential negative outcomes). Trump, on the other hand, is more likely to take actions that are bolder and less incremental in nature, but also more likely to cost him to some degree.

Collectively, that Clinton is more Conscientious and Agreeable, but less Emotionally Stable, suggests that she is likely to support substantive policy initiatives within the mainstream of the Democratic party that are likely to receive substantial majority support and/or are more incremental in nature, and she is likely to put forth the necessary effort to see them become law. Trump, on the other hand, is more likely to put forth bolder proposals with bigger potential costs, outside the mainstream of the Republican Party, but is also less likely to ensure that they are actually implemented.

The two major party candidates are indeed quite different in terms of their personality, and while much of the discussion thus far has focused on how their personality traits may or may not factor into voters’ decisions, comparatively less has focused on how their personality traits would affect how they govern (and the discussion on that note has typically focused on the traits of Mr. Trump). However, as we show in our book, personality traits are incredibly important for understanding how policies are formed and how elites behave more generally, and the above analysis provides a hint as to how the personality traits of Secretary Clinton and Mr. Trump could come into play once one of them enters the Oval Office.

This article is based on the paper ‘Measuring Elite Personality Using Speech’, forthcoming in Political Science Research and Methods, as well as the book More Than a Feeling: Personality, Polarization and the Transformation of the US Congress, forthcoming with the University of Chicago Press.

Featured image credit: Matt Popovich (Public Domain)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2eo36w4

______________________

Adam J. Ramey – New York University Abu Dhabi

Adam J. Ramey – New York University Abu Dhabi

Adam J. Ramey is an Assistant Professor of Politics, New York University Abu Dhabi.

Jonathan D. Klingler – Vanderbilt University

Jonathan D. Klingler – Vanderbilt University

Jonathan D. Klingler is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Department of Political Science, Vanderbilt University.

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. – University of Notre Dame

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. – University of Notre Dame

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of Notre Dame.