How did Hillary Clinton lose the Electoral College in this year’s election, while at the same time winning the popular vote? Maitreesh Ghatak writes that to understand Clinton’s loss, we need to examine the groups of voters who do not have steady voting patterns: energized voters, swing voters, and new voters.

How did Hillary Clinton lose the Electoral College in this year’s election, while at the same time winning the popular vote? Maitreesh Ghatak writes that to understand Clinton’s loss, we need to examine the groups of voters who do not have steady voting patterns: energized voters, swing voters, and new voters.

The winner of November’s US elections was not Donald Trump if we take into account all those who were eligible to vote. It was NOTA (none-of-the-above). The turnout rate was 57 percent, down from 58.6 percent in 2012 and 61.6 percent in 2008. It is true that some votes are still being counted and this could go up a bit, but it does not appear the picture will change drastically. One of the main reasons behind a low turnout rate is that a large number of adults in the US cannot register to vote and as a result, it is ranked 30th among developed countries in terms of the percentage of the voting-age public who are eligible to vote.

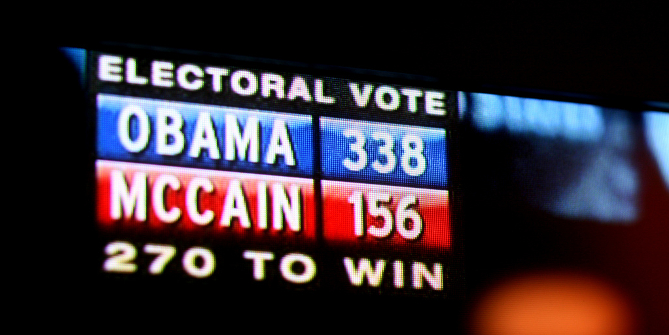

The winner of last month’s US elections was not Donald Trump even amongst all those who showed up to vote. As I write, Hillary Rodham Clinton has received more than 2.5 million popular votes than Donald Trump, giving her a margin of 2 percent. Therefore, the opinion polls, correctly criticized for getting the final outcome wrong, did not get the popular vote margin that wrong (3.5 percent was the average of various polls).

Yes, of course, the US has an Electoral College system. It is a bit like how under a parliamentary system it is possible for a party to win a parliamentary majority without necessarily winning a majority of nationwide popular votes. And Donald Trump won the Electoral College votes fair and square given the rules. Given the structure of the Electoral College system, a few battleground states play a major role in determining the final outcome. This election was effectively decided by 107,000 people in three states, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania (0.09 percent of all votes). None of these states, however, had voted for a Republican since 1988.

Now, to understand the outcome of elections, we should look not at groups whose voting pattern is steady. For example, Southern states tend to vote Republican and Coastal states tend to vote Democrat. More whites tend to vote Republican and more minorities tend to vote Democrat, more men tend to vote Republican and more women tend to vote Democrat.

Rather we should look at three groups of voters that can potentially change this pattern. First, the energized voters who normally stay home but are fired up enough at a given election to turn out and vote. Second, the swing voters who move from one party to the other in any given election. Third, the new voters (first-time voters and naturalized citizens).

In the three critical states that sealed Clinton’s electoral fate, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, the turnout percentage was lower than in 2012. It is likely that some of Bernie Sanders’ supporters or Obama’s supporters did not turn up as they did not find Clinton to be a credible enough candidate. This is consistent with the findings by a study by David Autor of MIT and his co-authors, which shows that areas more affected by job losses due to Chinese imports chose more ideologically strident candidates in congressional races. In Democrat-leaning states, these would be the Sanders voters, and in the heartland, these would be right-wing populists, represented by the Tea-party and now, strong supporters of Trump.

The second nail in the coffin of Clinton’s electoral prospects were swing voters. The number of registered Democrats (9 percent) who voted for Trump was higher than that of registered Republicans who voted for Clinton (7 percent). Around 10 percent of those who approved of Obama as President voted for Trump, while only 6 percent of those who disapproved voted for Clinton. As some of the interviews suggest, even some of the stereotypically Republican voters had voted for Obama because he was viewed more as an “outsider” than Clinton. Also, a small but significant minority of voters went for the Green or the Libertarian Party. If a good fraction of these voters, who are socially more liberal and so less likely to vote Republican, voted for Clinton especially in the critical states, the result could go the other way.

As far as new voters are concerned, first time voters voted two to one for Obama relative to Mitt Romney in 2012. In this election, they voted only marginally in favour of Clinton to Trump (56 percent to 40 percent). Clearly Clinton failed to enthuse millennials.

What about women voters? After all, this was a historic election where a woman was in striking distance of being elected US President. In an earlier piece, I suggested that all the factors were favouring a Trump victory except for the vote of white women. All the minority groups that he had repeatedly insulted during his campaign did not constitute an electoral block as big as that represented by women, who make up 52 percent of voters. This is where all the disadvantages that Trump faced concerning this particular demographic group was supposed to open the path for the first woman President of the United States. Sadly, this is where the narrative went horribly wrong for Clinton.

While Clinton received more votes from women in general than Trump (54 percent to 42 percent), more white women voted for Trump (53 percent to 43 percent) — and for Romney in 2012 (56 percent) than for one of their own kind. This could have made a vital difference in the battleground states. Despite all the sex scandals and misogynistic statements by Trump, the swing was relatively minor (Romney received 44 percent of the women’s vote in 2012, and 56 percent of the white women’s vote), while in the opinion polls the swing seemed much higher.

Clinton did worse than Obama in terms of turnout, swing, as well as first-time voters. Despite winning a majority of popular votes, she lost to a candidate repudiated by major sections of his own party. US voters were looking for change. Whether they get some spare change or get short changed is something we will have to wait to find out.

A version of this article appeared at the Business Standard.

Featured image credit: Oli Goldsmith (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2gQdNXT

______________________

Maitreesh Ghatak – LSE Economics

Maitreesh Ghatak – LSE Economics

Maitreesh Ghatak is Professor of Economics at LSE. He is Lead Academic on the IGC India-Bihar country team and Economic Organisation and Public Policy Programme Director at STICERD.