While almost all judgments from the Supreme Court are based on some kind of existing law, there are a small number which are not. Instead justices use public opinion, religious texts, and their own personal beliefs to justify their decisions. In new research, Chris Bonneau, Jarrod Kelly, Kira Pronin, Shane Redman and Matt Zarit examine whether such ‘extralegal’ decisions harm the Court’s legitimacy in the eyes of the public. They find that when moral or public opinion reasons are provided in addition to legal precedents, then public opinion about that decision’s legitimacy does not change. Members of the public only change their opinion on a decision’s legitimacy when they believe one specific reason is inappropriate and they disagree with the outcome.

While almost all judgments from the Supreme Court are based on some kind of existing law, there are a small number which are not. Instead justices use public opinion, religious texts, and their own personal beliefs to justify their decisions. In new research, Chris Bonneau, Jarrod Kelly, Kira Pronin, Shane Redman and Matt Zarit examine whether such ‘extralegal’ decisions harm the Court’s legitimacy in the eyes of the public. They find that when moral or public opinion reasons are provided in addition to legal precedents, then public opinion about that decision’s legitimacy does not change. Members of the public only change their opinion on a decision’s legitimacy when they believe one specific reason is inappropriate and they disagree with the outcome.

Despite the fact that nearly all opinions coming from the Supreme Court include some sort of legal basis for the decision, justices are not limited to strictly relying on existing law to justify their decisions. Indeed, there are numerous cases in which justices write opinions that contain reasons for their decision that are outside of the law, such as Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas. Some of the extralegal reasons that have been used by justices include public opinion, religious texts, and personal beliefs. While justices are certainly permitted to justify their decision with these types of extralegal sources, they are seen by some as illegitimate precisely because their foundation is outside of the law, unlike reasons that include the Constitution, precedent, or the text of statutes. But, does the public actually care about the reasons judges give for their decisions?

The above question is important given that the Court’s power rests largely on the public’s acquiescence to its decisions rather than on explicit constitutional provisions that the other branches of government enjoy. If certain rationales that justices use in their opinions can increase or decrease the legitimacy ascribed to the Court, then it suggests that the Court can control its own destiny when it comes to legitimacy.

Judging from public debates over many Supreme Court decisions, people do seem to care about how the courts reason. However, they also have conflicting ideas about how courts should reason. In a 2012 study, Gibson found that a large majority thought that state Supreme Court judges should strictly follow the rule of law. At the same time, well over 60 percent believed that judges should “state policy positions during campaigns,” and over 45 percent believed judges should “represent the majority.” Similarly, in the 2001 Justice at Stake Survey measuring opinions on the responsibilities of courts and judges, “making impartial decisions” was thought to be less important than “defending constitutional rights and freedoms,” and “ensuring fairness under law”. In other words, although people have a strong preference for procedural justice, a substantial proportion also believe that the court should do more than just strictly apply the law to a given case. This suggests that, grumblings about Supreme Court decisions being too political aside, extralegal reasons should not harm the public’s opinion of the Court too much, especially if the public expects the Court to use other criteria in its decision-making.

The studies on whether people’s personal preferences interfere with their appraisal of the court are similarly confusing: Swanson finds that people who disagree with a Supreme Court decision are less likely to support the Supreme Court in general, while Zink, Spriggs, and Scott find that people are more likely to agree with and accept a Supreme Court decision, even if they are ideologically predisposed to disagree, if the Court is unanimous and follows a precedent.

We were curious to make sense of these conflicting findings and designed an experiment to find out whether the kind of extralegal reasons that the Supreme Court commonly uses do any harm to the Court’s legitimacy in the eyes of the public. We expected decisions using only legal reasoning to generate higher levels of legitimacy toward the Court, and that extralegal reasons would harm the Court’s legitimacy only for those individuals for whom this defies their expectations of decision-making. We also expected individuals who agree with the Court’s decision will give the Court higher levels of legitimacy regardless of the reasons given by the Court.

The participants in the experiment were shown a short paragraph describing the outcome of a case in which the Court ruled against restrictions on campaign finance. The reasons provided by the Court as justification for the decision varied across participants, and could include a legal reason (based on precedent) and/or extralegal reasons (based on public opinion polls or moral arguments). In one set of conditions, extralegal reasons were always paired with precedent and in another set of conditions participants only received the extralegal reasons. This approach allows us to examine whether extralegal reasons can harm the legitimacy of the Court both when they are paired with more traditional legal reasoning and when they are presented alone. This resulted in six possible conditions (precedent only, precedent and public opinion, precedent and moral argument, no reason, public opinion only, moral argument only). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the six conditions.

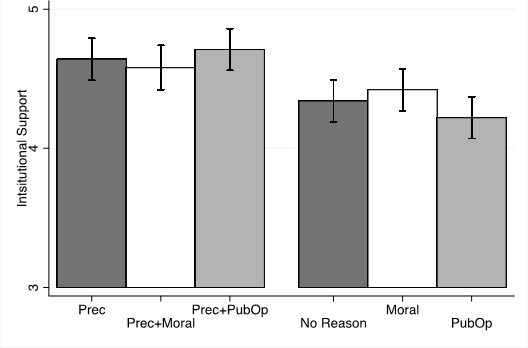

We find that the reasons justifying the decision do not affect the perceptions of Supreme Court legitimacy. As shown in Figure 1, when moral or public opinion reasons are provided in addition to precedent (the three bars on the left), legitimacy is no different than when precedent alone is provided. In addition, legitimacy does not differ between participants provided with absolutely no reason at all for the decision and when moral or public opinion reasons are provided (the three bars on the right). Thus, overall the reasons used by the justices to justify a decision do not appear to harm perceptions of legitimacy toward the Court.

Figure 1- Institutional Legitimacy by Reasons Provided for the Decision

Yet it could be the case that extralegal reasons do harm legitimacy, but only when participants believe that the reasons used are inappropriate. To account for this possibility, approximately one week prior to the experiment we asked participants whether certain rationales are appropriate for the Court to use. Thus we could measure perceived legitimacy across levels of “expectations violation,” or the degree to which individuals find a reason to be appropriate.

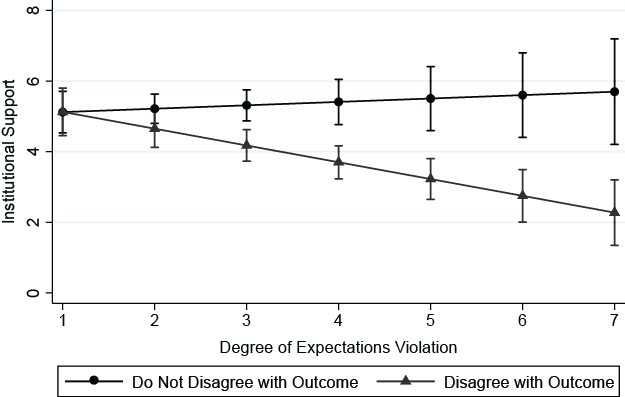

Here, we do find that when participants find the use of one specific type of reason inappropriate, and when they disagree with the outcome, legitimacy is harmed. However, it was not one of the extralegal reasons. As shown in Figure 2, legitimacy was lower only among participants that found the use of precedent to be inappropriate and who disagreed with the decision (compared to those who also found precedent inappropriate and agreed with the decision). Why? Well, if you think the Supreme Court got a previous decision wrong, you are more likely to think they should fix the error rather than double down on a mistake.

Figure 2 – Predicting Institutional Legitimacy by Degree of Precedent Expectations Violation and Agreement with Outcome

And, contrary to expectations, participants who found public opinion inappropriate, and who received that reason as a justification, reported higher legitimacy than those who found it appropriate to be used (see Figure 3). Thus, not only did public opinion not harm legitimacy among those who did not initially approve of its use, it resulted in higher legitimacy. This occurred regardless of agreement or disagreement with the outcome. Thus, participants may have been pleasantly surprised at the use of this particular reason to justify the decision.

Figure 3 – Predicting Institutional Legitimacy by Degree of Public Opinion Expectations Violation and Agreement with Outcome

Overall, these results show that extralegal reasons are unlikely to harm the legitimacy of the Court. Our results are consistent with a large body of research showing that it’s very hard to diminish the legitimacy of the Court. The robustness of institutional legitimacy should be comforting to all of us, but especially those who think the Court is experiencing a crisis of legitimacy.

This post is based on the article, “Evaluating the Effects of Multiple Opinion Rationales on Supreme Court Legitimacy” in American Politics Research.

Featured image: Supreme Court Chamber Credit: Phil Roeder (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2jg2jjR

______________________

Chris W. Bonneau – University of Pittsburgh

Chris W. Bonneau – University of Pittsburgh

Chris W. Bonneau is associate professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh and co-editor of State Politics and Policy Quarterly. His research focuses on judicial politics and state politics.

Jarrod Kelly – University of Pittsburgh

Jarrod Kelly – University of Pittsburgh

Jarrod Kelly is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Pittsburgh. His research focuses on American politics and political behavior.

Kira Pronin – University of Pittsburgh

Kira Pronin – University of Pittsburgh

Kira Pronin is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research interests are in comparative politics and judicial politics.

Shane Redman – University of Pittsburgh

Shane Redman – University of Pittsburgh

Shane Redman is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Pittsburgh. His research interests are in judicial politics and political behavior.

Matt Zarit – University of Pittsburgh

Matt Zarit – University of Pittsburgh

Matt Zarit is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Pittsburgh. His research interests are in American politics and executive politics.