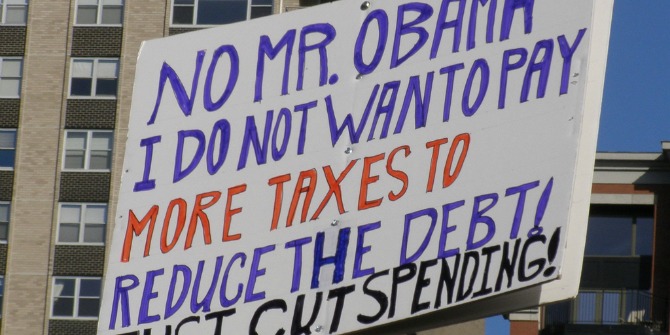

A large segment of support for the Republican Party is made up of white, working class voters, a group which would likely benefit more from the redistributive measures advocated by the Democratic Party. In new research, Kieran Bezila, with collaborators Monica Prasad and Steve Hoffman, investigates this seeming contradiction, by looking at the economic dimension of moral and cultural appeals. He argues that pragmatic economic concerns are important to working-class voters, concerns which translate to a dislike of redistributive policies advocated by the Democratic Party which they see as “spendthrift” and imprudent.

A large segment of support for the Republican Party is made up of white, working class voters, a group which would likely benefit more from the redistributive measures advocated by the Democratic Party. In new research, Kieran Bezila, with collaborators Monica Prasad and Steve Hoffman, investigates this seeming contradiction, by looking at the economic dimension of moral and cultural appeals. He argues that pragmatic economic concerns are important to working-class voters, concerns which translate to a dislike of redistributive policies advocated by the Democratic Party which they see as “spendthrift” and imprudent.

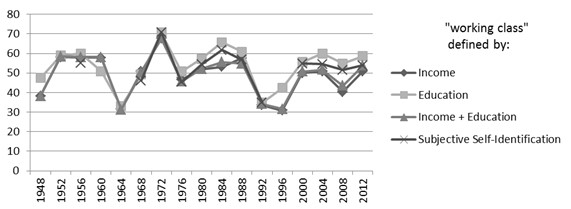

One of the puzzles of contemporary voting behavior is why working class voters do not reliably vote for parties of the left that support redistributive measures that would directly benefit them. For Fexample, as Figure 1 shows, one-third to one-half of the American white working class votes Republican, and this is true whether one defines working class by income, education, a combination of the two, or subjective self-identification (the data from the latest election are not yet available). A common explanation, that moral or cultural values (such as attitudes on immigration, abortion, race, etc.) trump economic concerns, has been the subject of much debate among scholars, without a clear resolution. The vast majority of empirical work done on this question has drawn on survey data.

Figure 1 – White working class support for Republicans

Note: Presidential elections, percent voting for Republican candidates, 1948-2012, using different definitions of “working class”. Source: National Election Studies, SDA Archive, sda.berkeley.edu. Income: less than 33 percent percentile (1948-2004), less than $35,000 (2008, 2012). Education: less than Bachelor’s. Subjective self-identification: working class.

In new research, we provide a new direction for this debate by changing methods and offering a new argument. Drawing on in-depth personal interviews with 120 white working class voters in “Pleasant Park”, a Midwestern American town with a predominantly white (over 95 percent in the last Census) semi-skilled population, we argue that moral and cultural appeals do matter to these voters, but these moral and cultural appeals have an economic dimension: voters believe that these moral behaviors are the ones that will help them prosper economically. We argue that our respondents work to sustain a worldview and lifestyle that they see as in their general economic interest, and that specific issues and behaviors become implicated in that worldview and lifestyle. This worldview and lifestyle are often articulated in the discourse of morality. But this discourse is neither arbitrary, nor driven only by the need to create social status distinctions between different social group by identifying some people and behaviors as moral or immoral. Instead, pragmatic economic concerns are woven throughout.

One intriguing example of the economic embeddedness of moral values concerned the meaning of the word “conservative” for our respondents. When not being employed as a general political label, its most frequent substantive use was, surprisingly, not in reference to abortion, immigration, gay rights, or any other hot-button American conservative issue, but in regard to personal finances: for our respondents, being “conservative” in daily life meant first-and-foremost managing one’s own money properly, not being a spendthrift, and thus fulfilling the moral obligation to take care of oneself without relying on others for help or aid, a sign of moral weakness.

We term this practice of adhering to certain moral behaviors in order to prosper economically “walking the line”, and it’s something our respondents associated with the policies and philosophy of the Republican Party. By contrast, Democrats were often seen as a spendthrift party that shamelessly bought votes with various ‘bribes’ (social welfare programs, such as government subsidies to the indigent for cell phone service, were frequently invoked) with little concern for long-term fiscal responsibility or, perhaps more importantly, the moral example it was setting by rewarding the ‘lazy’ and making people believe that the job of government was to ‘give them things for free’.

Throughout our interviews, we encountered repeated avowals of the importance of walking the line and cautionary tales of those who failed to do so, creating a ripple-effect of trouble for themselves and those around them. These concerns were amplified by the economic stress members of the American working class in general, and our respondents specifically, were increasingly under: “Pleasant Park” had undergone a significant decline in its base of light manufacturing in recent decades, leading – in our respondents’ telling – to a cascade of personal and social ills. Embracing an ethos of “walking the line” was often cited as the obvious logical and moral response to these problems.

We believe that for many of our respondents, Republican voting is part of a larger strategy of trying to prosper economically by learning, incorporating, and displaying the attributes that they believe lead to economic success, including avoiding excessive spending and debt. When good jobs are scarce, behaviors that are seen as helping in the competition for good jobs become more salient for working class voters, and these voters are drawn to politicians who speak about the considerable personal efforts these voters are making to get and keep jobs. This may be a more durable feature of the working class – helping to answer the perennial question of why working class voters do not always vote for working class parties – or it may have been strengthened by recent deindustrialization.

This explanation does not exclude the consideration of the importance of moral values as motivators of voting behavior – indeed, we encountered a variety of voters who felt strongly and singularly about issues such as abortion and gay rights – but it does suggest that creating a binary between economic appeals and moral/cultural values, and arguing that the latter trump the former, is simplistic and likely substantively wrong.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Walking the Line: The White Working Class and the Economic Consequences of Morality’, in Politics & Society.

Featured image credit: Marissa Babin (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2k93aB1

_________________________________

Kieran Bezila – Beloit College

Kieran Bezila – Beloit College

Kieran Bezila is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Beloit College. His research interests include politics, altruism and prosocial behavior, and the social organization of everyday knowledge and decision-making.