As Donald Trump forms one outrageous policy after another, and as the UK government remains unclear as to what future it is pursuing for the country post-Brexit, Eric Kaufmann discusses the factors that led people to back populist rhetorics with editors Chris Gilson and Artemis Photiadou.

As Donald Trump forms one outrageous policy after another, and as the UK government remains unclear as to what future it is pursuing for the country post-Brexit, Eric Kaufmann discusses the factors that led people to back populist rhetorics with editors Chris Gilson and Artemis Photiadou.

Recent developments in Western politics – the most recent being the US travel ban – seem to come from an opposite universe, in that we used to see the West as being liberal and secular. Having researched cultural values, are these developments as shocking to you or did you see this coming?

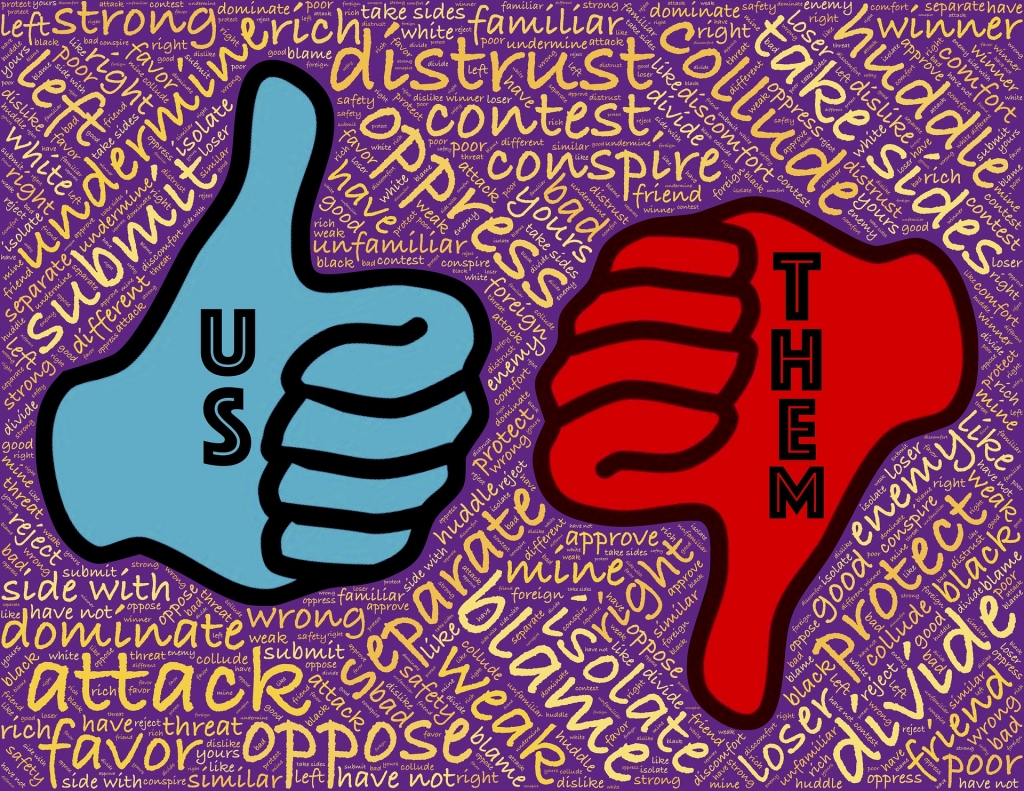

I don’t think any of us were good at predicting developments but I do think there were factors one could have pointed to. What we see is a growing polarisation of values in Western societies. So while the political divide used to be about Left vs Right, about economic redistribution and the free market, the new emerging polarisation is what you may call culturally open vs closed, or cosmopolitan vs nationalist. It’s a cultural war but it’s really over the “who are we” question – who are we as a nation.

Is American populism (pro-Trump) the same as British populism (pro-Brexit)?

I think there are many similarities. In looking through the survey and election data I find a lot of parallels: immigration, to some extent terrorism, and the Syrian refugee issue – there is no better issue to pick up polarisation over Trump than views on Syrian refugees. And we also see with Brexit that immigration was the number one issue driving the vote. These are not the only issues but most are value-based ones.

You also have the impact of the split between those who think the world is a dangerous place and want to be safe, and those who are oriented differently and like novelty and exploration. And so that divide turns very strongly on the death penalty question – those who are pro death penalty are also pro-Brexit and pro-Trump. So we see similar attitudes. But the immigration question is important because it explains the “why now” question – we’ve always had people backing the death penalty or being against it.

So why now? The UK has had waves of immigration since the 1950s and the US has historically been a nation of immigration. And would it be fair to say that continuity sounds like a euphemism for resentment for those who are different to the majority – culturally or perhaps in terms of opportunity?

You need to look at each country and the nature of the flows. The proportion of those in European countries – of foreign-born – we haven’t seen that proportion in the past. In the US, the last time we had over 13% foreign-born was in 1900-1920, a period of quite intense, anti-immigration politics. So in a way the more surprising thing would have been if there was nothing happening.

You need to look at each country and the nature of the flows. The proportion of those in European countries – of foreign-born – we haven’t seen that proportion in the past. In the US, the last time we had over 13% foreign-born was in 1900-1920, a period of quite intense, anti-immigration politics. So in a way the more surprising thing would have been if there was nothing happening.

The resentment – I think it’s largely driven by the cultural dimension you mention. I don’t think the resentment of the elite is based on the fact that people have more money or opportunity. Economic resentment is not really driving it. I think the resentment is of a perceived cosmopolitan elite that has brought these cultural changes. So it’s focused more on a liberal cultural and political elite rather than towards someone like Donald Trump, who is very elite in an economic way but not in a cultural one.

Is there a demographic divide in the distribution of personal values?

Definitely. Younger voters, people with university degrees certainly would be more liberal on all these cultural dimensions with a few exceptions. But the important point is that those demographic factors actually only explain a small share of the variation in attitudes. So you have people with degrees who are actually conservative, and people without degrees who are very cosmopolitan.

Education is one of the most important demographics. Not income, not class – education is what splits the data, more so than age. But even education is not as important as values. If you ask a specific question such as support for the death penalty, those will come out stronger than education [in predicting right-wing populist support]. Education is important because it signals a worldview, rather than because it is a marker of income, or class, or status in that way. So education is linked into that cultural worldview divide that I talked about.

Will cutting off the flow of immigration counter right-wing populism?

I don’t think cutting off immigration is an option given the many needs of modern societies. Granted we can talk about immigration levels and that’s an important debate and I think there has to be an accommodation of different needs – a happy medium. But I think that more important than that is the “who are we” question. I don’t think it’s enough to talk about where is France headed, where is Britain, where is America going, or what does diversity and immigration mean for France or Britain or America. The real question is [not so much what does it mean to be British but] what does it mean to be white British in an age of large-scale migration. The question is, as a member of the ethnic majority, where do you see yourself and your group moving?

Politicians have not been able to address that and that’s part of where I come up with this idea of having different messaging for different people. You need to get people reassured that we won’t see a radical change, it’s not that society will get more and more diverse and the majority will shrink and shrink and shrink – which is kind of the way people think it is. We need to counter this story of rapid transformation and replace it with what’s fairly likely: modest transformation and things staying the same.

How easy is it to change someone’s beliefs – people are now seeing that their concerns over immigration can be turned into racist policies, like the US travel ban. Would it be enough to make someone change their stance?

Social science research would suggest that it is very difficult to change people’s beliefs. That’s not to say that at the margins some people won’t be turned off by those current policies. But I think what’s likely to happen is actually a deepening of the divide and a deepening of polarisation, partly because we don’t have a centre ground that seems to be more nuanced on this question of racism.

A lot of the people who say the Muslim ban is racist – which it is – also call the wall with Mexico racist – which I don’t think it is. You can be in favour of a wall and not be racist, whereas it is not possible to be in favour of a ban and not be a racist. That’s an important distinction. And if people who support the wall say “well, whatever we support will be called racist,” they may then be desensitized and not be outraged when racist policies like the Muslim ban are put into place. That’s my concern. There should be a centre ground where we can say certain things are racist and outrageous, and other things we may not like but are not racist. Part of the problem is slinging this racism epithet around and that sharpens the divisions; each side starts to get a very one-dimensional view of the other.

Are you dealing with these issues in your forthcoming book?

The new book with Penguin will be all about the white majorities in the West in a time of ethnic transformation – how they are responding to an age of migration and ethnic transformation. And I am arguing that there are a number of responses. You get the populist anti-immigration response, trying to oppose immigration; you get a residential response in the form of white avoidance, with white majorities retreating away from diverse areas and networks; and then you also get an assimilation, an intermarriage, and contact response. And these are not mutually exclusive.

Part of what I will be arguing is that the nature of the white majority will change over time and will increasingly move to be what we would now consider a mixed-race population – most members of the “white majority” will have [an admixture of] non-white non-European background. But that doesn’t mean that they are going to stop thinking like a majority. There will be a lot more continuity than we imagine, there’s not going to be this radical shift and overhaul. But of course, the book remains to be written!

Note: A version of this article first appeared at the LSE’s British Politics and Polic blog. Eric Kaufmann spoke at an event hosted by the LSE Institute of Public Affairs.

Featured image credit: Pixabay (CC0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2k3quj9

_________________________________

Eric Kaufmann – Birkbeck College

Eric Kaufmann – Birkbeck College

Eric Kaufmann (@epkaufm) is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College and is writing a book about the White majority response to ethnic change in the West (Penguin).

Why do so many public intellectuals continue to talk about a supposed ‘polarization’?

When looking at decades of polling, public opinion has shown a majority of the US population shifting left. There is no evidence of a large and consistent rift. Even in the Deep South, the majority living there either votes or leans toward the Democratic party, despite the GOP controlling the region through anti-democratic tactics (voter suppression, gerrymadering, etc).

Consider some central issues. Most Americans support both abortion rights and abortion regulation, gun rights and gun regulation. Consider other issues. Most Americans, when informed of how high inequality is in the US, support decreasing inequality. Most Americans, when given a choice of rehabilitation, support non-punitive methods of dealing with crime. But the ruling elite control what Americans know through the media and what choices they get in polls and at the voting booth.

It is only the political elites, activists, and upper classes who are divided, but they are a minority of the population. Yes, a powerful minority that controls the government, parties, economy, media and polling — yet still just a minority. The problem is that the minority, which includes public intellectuals claiming polarization, are mostly only talking to other members of this minority. The rest of the population is kept in the dark, not realizing that they are a majority with the only major divide being economic.

What if if public intellectuals are helping to create polarization, rather than merely observing and studying it?

And in doing so, what if public intellectuals (intentionally or unintentionally) are helping the ruling elite to keep the population divided or rather creating the false sense of division and divisiveness?

Worse still, what if pushing the narrative of polarization eventually can cause actual polarization and so initiates a self-fulfilling prophecy?

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2017/02/16/polarizing-effect-of-perceived-polarization/