Politics has been filled with angry rhetoric. And politicians, such as Donald Trump, have used anger to their electoral benefit. But what are the political consequences of an angry political environment. Research by Antoine Banks shows that anger (unrelated to racial and ethnic groups) causes ethnocentric whites to be more opposing of policies considered to benefit racial and ethnic minorities. But, it also causes those low in ethnocentrism to defend the rights and interest of these groups.

Politics has been filled with angry rhetoric. And politicians, such as Donald Trump, have used anger to their electoral benefit. But what are the political consequences of an angry political environment. Research by Antoine Banks shows that anger (unrelated to racial and ethnic groups) causes ethnocentric whites to be more opposing of policies considered to benefit racial and ethnic minorities. But, it also causes those low in ethnocentrism to defend the rights and interest of these groups.

“Law and order”, “states’ rights”, “welfare queen”, “illegal immigrants”, and “building a wall” are political catch phrases U.S. politicians have employed to cause white Americans to think of politics as ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Researchers have demonstrated that when politicians make a group conflict salient (e.g.. illegal immigrants coming across the U.S. Mexican border), ethnocentrism becomes more important in American public opinion. Ethnocentrism is a broad view of prejudice where ethnocentric individuals characterize themselves and members of their in-group (e.g. whites) in a positive fashion while out-group members (e.g. blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans) are perceived negatively.

I was interested in testing whether group threat needs to be present for ethnocentrism to matter in American public opinion. Are there more inconspicuous conditions causing whites to engage in ethnocentric thinking? My research turned to emotion for an answer. I proposed that anger itself – unrelated to racial and ethnic minorities – could produce a similar effect. Feeling angry about the national economy, a crumbling infrastructure, or the cost of college could cause whites to scapegoat racial and ethnic minorities and thereby oppose policies that are intended to benefit these groups. My argument is that general anger should not only activate whites’ negative attitudes toward racial and ethnic minorities but their positive attitudes toward these groups as well. Why might general anger bring to mind whites’ racial and ethnic attitudes?

Most ethnocentric whites believe members of their in-group are hardworking, honest, and friendly while out-groups are considered lazy, untrustworthy, and hostile, they blame out-groups for their own misfortunes. According to research on emotion, blame appraisals are central to whether someone experiences anger. As a result, I suspected that anger should be strongly linked to ethnocentric attitudes among whites because they blame racial and ethnic minorities for their disadvantaged status in society. I also suspected that anger should be linked to whites’ positive racial and ethnic attitudes. These are whites that score low in ethnocentrism and believe racial inequality is due to individual and institutional racism. Instead of thinking the moral character of racial and ethic minorities is the problem; the least ethnocentric believe it is the unfair treatment of these groups. After repeated exposure to this information over time, anger becomes tightly linked to whites’ group attitudes. Since anger is strongly linked to whites’ racial and ethnic attitudes, experiencing anger, even unrelated to these groups, should set group thinking into motion.

Specifically, my expectation was for anger, unrelated to racial and ethnic groups, to increase opposition to racial and immigration policies among ethnocentric whites. I also predicted that the same anger should increase support for racial and immigration policies among whites that score low in ethnocentrism. On the other hand, I suspected that non-racial/ethnic fear should not drive ethnocentric whites to be more opposing of racial and immigration policies.

Study One uses a national adult experiment to test my predictions. The experiment induces anger, fear, and relaxation unrelated to racial and ethnic groups. For example, subjects are asked to write about things in general that make them feel angry. The experimental findings show that when ethnocentric whites are put in an angry state they are more opposing of racial and immigration policies relative to similar ethnocentric whites not made to feel angry. Meanwhile, the fear induction has no effect on ethnocentrism.

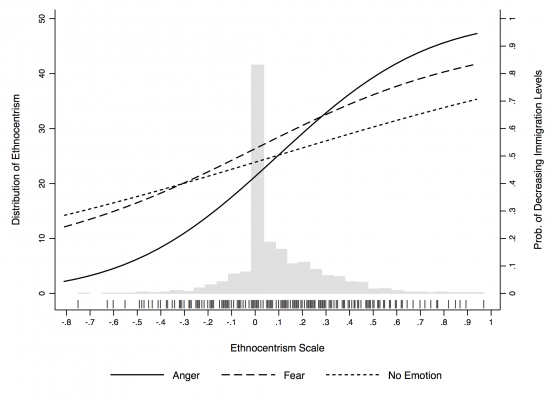

Study Two relies on the American National Election Study cumulative file (years 1992-2004) to determine if my experimental results hold up with different emotion measures, across time, and a nationally representative sample. The emotion items are about the presidential candidates. For example, survey respondents are asked if Bill Clinton (or George W. Bush) has ever made you feel angry/afraid. The benefit of these measures is that racial or ethnic groups are not the objects being evaluated. Thus, the items allow me to test the effect anger, unrelated to groups, has on ethnocentrism. Below I present the results for opinions toward immigration.

Figure 1. 1992-2004 ANES: Probability of Whites Support for Decreasing Immigration Levels Across Emotions as Their Level of Ethnocentrism Changes

Figure One shows the probability of decreasing immigration levels at varying levels of ethnocentrism conditional on whites’ emotional experience. We see that anger pushes ethnocentric whites to be more willing to decrease immigration levels and those that score low in ethnocentrism to be more opposing of such a policy – relative to those that do not experience anger.

All in all, across both studies, the findings show that non-racial/ethnic anger causes group thinking to enter into American politics. Even when the anger is not directed at racial and ethnic minorities, ethnocentrism matters more in American public opinion. These results help us understand how anger-inducing events (e.g. personal financial troubles) can cause certain whites to scapegoat racial and ethnic minorities while persuading other whites to defend the rights and interests of these marginalized groups.

This article is based on the paper “Are Group Cues Necessary? How Anger Makes Ethnocentrism Among Whites a Stronger Predictor of Racial and Immigration Policy Opinions” in Political Behavior.

“Ethnocentric Bumper Sticker” by Wesley Fryer is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2uhO8yk

_________________________________

Antoine Banks – University of Maryland, College Park

Antoine Banks – University of Maryland, College Park

Antoine Banks is an Associate Professor in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland. He is also Director of the Government and Politics Research Lab. His research interests include racial and ethnic politics, emotions, political psychology, and public opinion. His book, Anger and Racial Politics: The Emotional Foundation of Racial Attitudes in America, published by Cambridge University Press, explores the link between emotions and racial attitudes and the consequences it has for political preferences. His articles have appeared in journals such as American Journal of Political Science, Public Opinion Quarterly, Political Behavior, Political Analysis, and Political Psychology.

Interesting. His theory is plausible with a vague link to the Realistic Conflict theory – except this argument suggests it is misplacing blame for people’s own unfortunate situations that leads to prejudice. I agree that Trump uses this anger and directs it at ethnic minorities, it’s sadly the reason he won the election. It makes you think how much people are easily influenced.