The US Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision prompted many questions both at home and overseas as to how much influence special interests should have on political campaigns. Andrea Lawlor and Erin Crandall look to Canada and the UK as examples of how these interests can be managed well in an era where money equals political speech. They find that each system has strengths that other lacks, and that both will need to grapple with the growth of low-cost social media influence on election campaigns.

The US Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision prompted many questions both at home and overseas as to how much influence special interests should have on political campaigns. Andrea Lawlor and Erin Crandall look to Canada and the UK as examples of how these interests can be managed well in an era where money equals political speech. They find that each system has strengths that other lacks, and that both will need to grapple with the growth of low-cost social media influence on election campaigns.

How a country regulates its elections matters to how its citizens view the legitimacy of those elections. Different regulations can create different electoral outcomes and arguably just as important, these regulations can be understood as an expression of a country’s democratic values. Questions regarding how money should be spent, on what and by whom are at the core of these regulatory choices and are frequently contested in both the political and legal arenas. One of the most well-known examples of this is the US Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, which has reverberated globally, prompting questions about whether money should, indeed, be equated with free speech, and to what degree special interests (called “PACs” in the US, “third parties” in Canada and “non-parties” in the UK) should be allowed to influence campaigns.

Though perhaps less high profile, Canada and the UK have also dealt with these politically consequential questions. Elsewhere, we’ve set out the extensive similarities between these two countries and why they are useful comparators. But, in short, both have made significant policy reforms in the past two decades that have changed how third parties (unions, group interests, businesses and individuals who participate in an election campaign by advertising for or against issues of concern or candidates and political parties) can participate in elections and referendums. And unlike in the US, they regulate election advertising such that these third parties can only spend within set limits.

Compared with the amounts spent by US special interests, third party spending limits are relatively modest in both countries. With the regulatory reforms introduced in 2014, UK third parties are permitted to spend £319,800 in England for general advertising during the regulated campaign period (the equivalent of 2 percent of a political party’s maximum campaign expenditure limit), amounting to a spending cap of £9,750 per constituency. The 2014 changes also introduced regulations for party-targeted advertising. In Canada, current third party spending limits have been in place since 2000, and, in 2017, place a maximum spending limit of $211,220 for a national third party campaign, of which no more than $4,224 can be spent in an electoral riding to promote or oppose a candidate. These limits are adjusted for inflation each year, and since 2014 are also adjusted if the regulated campaign period exceeds 37 days (during the 78-day 2015 election, these limits amounted to $434,000). This amounts to less than 1 percent of a political party’s campaign expenditure limit.

Comparing how money in politics is regulated

While third parties are not themselves looking to be elected, they often do share the same aims and objectives as political parties. Election policies that ban or severely limit the participation of third parties may suppress the views of those not represented in political parties. On the other hand, placing no limits on third party spending may create a situation where wealthy political interests (akin to the US’ Koch brothers) can dramatically outspend political parties and candidates, as well as other grassroots or local third parties without the financial means to undertake comparable campaigns. Both over-regulated and under-regulated campaign environments can be detrimental to democratic participation.

“5 5 5 5 5 5….” by ~lzee~by~the~Sea~ is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

Given the potential impact that reforms to regulations can have on elections, an important question to ask is: why have these countries attempted to regulate third party spending and has it worked? Understanding the overall performance of an election regime requires us to reflect on the utility of its regulations and revise them when they fall short of their intended outputs. In our recent research, our goal is to build an evaluation framework for these election campaign policies and test the administrative strengths and weaknesses of third party regulations in Canada and the UK from 2000 to 2016. We evaluate whether these policies meet four of their stated goals, broadly classified as:

- Efficiency – Clarity of regulations and ability of third parties to follow regulations with reasonable effort;

- Effectiveness – The ability of the policy to regulate spending in a manner consistent with its outlined goals;

- Accountability – The ability of the monitoring agent to publicly report on its work.

- Transparency – The clear identification of financial and non-financial contributions to the campaign by third party actors.

Evaluating Policy Outcomes

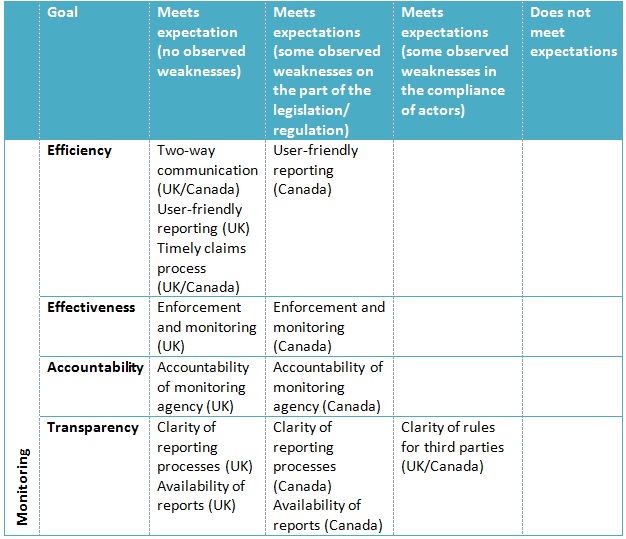

Looking across legislative, administrative and regulatory documentation, published financial and administrative data, and publically stated motives in policy documentation, media reports and public speeches, we are able to determine how well third party spending regulations in each country meet their outlined goals. In particular, we were interested in a few metrics around communication between third parties and regulators, clarity of processes/rules, enforcement of regulations, and accountability to parliament. Our findings suggest that each country’s evolving third party regulatory regime do in many cases meet expectations (see Table 1 below).

Table 1 – Policy Evaluation of Third Party Spending Regulations

Importantly, each country has strengths that the other lacks, suggesting that electoral commissions could learn from one another’s experiences. In particular, the UK’s approach to reporting was viewed as particularly easy to use and submit, enhancing the likelihood of regulatory compliance. The Canadian system was noted to be particularly responsive to the concerns and queries of third parties during the campaign. Both regulators ensured that reports were publically available in a timely fashion.

One area where both countries can strengthen their regimes is in the clarity of rules for third parties. According to interviews we conducted, some third parties expressed concern that they might be found in violation of some of the more ambiguous rules, and therefore erred on the side of overreporting – an activity, while good for transparency, can be also be viewed as a significant administrative burden for smaller organizations. The area in which this concern was most evident was social media. Use of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and other social media tools is a burgeoning area of marketing and political communications. However, the low/no-cost nature of social media also presents a policy challenge given that the traditional regulatory model for election advertising equates speech with spending. This highlights a new challenge for election regulators: how to regulate impact that isn’t measured in financial terms.

The importance of carefully monitoring electoral participation by interests – particularly those with substantial financial influence – can hardly be understated in the contemporary climate of concern about money in politics. Analyses like these thus become important not only in keeping special interests accountable, but also for helping regulators navigate the challenges of an evolving campaign environment.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Comparing third party policy frameworks: Regulating third party electoral finance in Canada and the United Kingdom’, in Public Policy & Administration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2z7CwAc

_________________________________

About the authors

Andrea Lawlor – King’s University College, Western University

Andrea Lawlor – King’s University College, Western University

Andrea Lawlor is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at King’s University College, Western University in London, Canada. Her research focuses on media and public policy, particularly in the areas of immigration, social policy and campaign finance policy.

Erin Crandall – Acadia University

Erin Crandall – Acadia University

Erin Crandall is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Politics at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, Canada. Her research focuses on Canadian law, politics, and public policy, particularly in the areas of judicial appointments, constitutionalism, and election finance policy.