In 2013, the New York City Housing Authority shelved its proposal to fund improvements to its housing stock by leasing undeveloped land. Shomon Shamsuddin writes that despite opposition from residents, such plans can be of great benefit to those living in public housing if they preserve existing homes, increase density and add affordable housing units.

In 2013, the New York City Housing Authority shelved its proposal to fund improvements to its housing stock by leasing undeveloped land. Shomon Shamsuddin writes that despite opposition from residents, such plans can be of great benefit to those living in public housing if they preserve existing homes, increase density and add affordable housing units.

Housing is increasingly expensive in many US cities, especially New York where the average rent for a two bedroom apartment is more than $4,000 per month. For more than 80 years, public housing has provided affordable shelter for low-income New Yorkers but the combination of aging buildings, declines in funding, unfulfilled repair orders, and questionable fiscal management have raised questions about the future of the projects. When the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) proposed to fund needed building improvements in 2013 by leasing its undeveloped land, residents criticized the plan and it was shelved.

What happened? Let’s reexamine the plan in context.

NYCHA manages a massive operation: nearly 2,500 buildings with 175,000 apartments, or one out of every 11 apartments in the city. It is the landlord for almost 400,000 people, which is approximately the population size of Miami.

But the housing authority faces severe financial pressures. Since 2001, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development has reduced NYCHA’s operating subsidies and capital funding by a combined $1.5 billion, while the city and state have completely eliminated funding for 21 developments. As of 2015, unmet capital needs (for example, repairing roofs, upgrading heating and ventilation systems, and replacing elevators) were projected to exceed $13 billion.

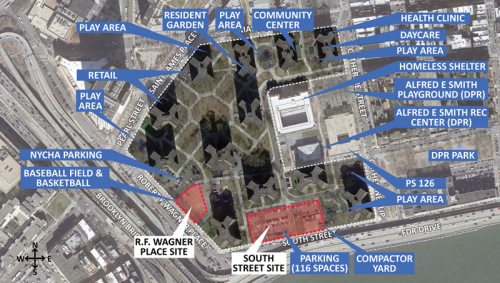

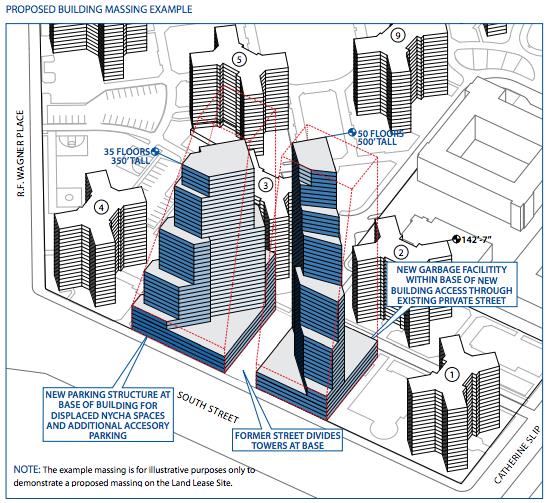

To address the funding shortfall, NYCHA proposed to offer 99-year ground leases on land parcels in selected public housing sites to private developers for residential construction. The basic idea is that current zoning allows for far more housing than currently exists on the sites. Housing is in high demand in New York but land is scarce so developers would pay for the opportunity to build; the revenue would help pay for public housing improvements. The plan also required that 20 percent of newly built housing units would be affordable to low-income households.

Despite the potential benefits, public housing residents opposed the plan for several reasons. The undeveloped land parcels had important social meaning and uses for residents, including playgrounds, basketball courts, baseball fields, and parking lots. These open spaces are valuable amenities, particularly in dense cities like New York.

Most of the proposed new residential buildings would literally tower over their public housing neighbors. For example, the design guidelines for the Smith Houses South Street parcel show a rendering of a proposed building that is 50 stories tall, which is more than triple the height of the existing public housing on site.

Other residents expressed fears of gentrification and eventual displacement. One tenant asked, “First the parking lots. What’s next? … Where will the poor go?” Officials also framed the plan in financial terms, which suggested NYCHA was primarily concerned with funding and fiscal deficits, while resident needs were a secondary consideration. Based on their past experience with the housing authority, residents simply did not trust officials to do what they said they would do.

However, the plan also featured some interesting and unconventional ideas for reimagining public housing:

First, the plan would preserve every public housing unit on site, in contrast with the steady decline in the overall number of public housing units around the country due to demolition and redevelopment. Baltimore, Chicago, and other cities have systematically torn down high-rise public housing structures, in part because they are notoriously associated with crime, violence, and social disorder.

Second, the plan offered a new approach to deconcentrating poverty on site by increasing residential density. The typical strategy for reducing the proportion of poor households in public housing redevelopment is to build fewer replacement units for demolished public housing and to offer vouchers to residents to permanently move elsewhere. In contrast, the plan would decrease the proportion of low-income families by bringing in market rate residents and increasing the total number of households. This approach offered the added benefits of potentially increasing local economic activity and neighborhood safety; preserving vital social networks and established community relationships; and enabling public housing residents to remain in their homes.

Third, the plan would add affordable housing units to public housing sites. Concerns about the effects of concentrated poverty have led many cities to try to locate new affordable housing away from low-income areas. The plan would not only benefit public housing residents, it would also address the broader need for affordable housing among low-income communities.

“Governor Alfred E. Smith houses” by -JvL- is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Fourth, the plan proposed to create mixed-income communities by attracting market-rate residents to live around public housing families, in addition to mixing incomes within buildings. Typically, public housing redevelopment projects produce mixed-income communities through a combination of moving some low-income families out and bringing market-rate residents in so that there is a mix of household incomes within a building. The plan envisioned mixed-income communities on a larger scale by constructing market-rate housing so that there is also a mix of household incomes between buildings. This is similar to the standard process of housing development in New York and elsewhere except that market-rate housing would be located on the same site as existing public housing. Bringing in more market-rate residents could improve the quality of local goods and services but the siting of the new buildings could contribute to low-income residents becoming more isolated from other households.

Although the initial plan was cancelled, it was successful in shifting the conversation from if public housing land will be developed to how it will be developed. The latest proposal introduced by Mayor Bill de Blasio calls for engaging residents in a plan to build more affordable housing for low-income families. The plan, named NextGeneration NYCHA, takes additional housing development on public housing land as a given while changing the proportion of units to be 100 percent affordable in some locations and up to 50 percent affordable and 50 percent market rate in others.

This balance may be more politically palatable to affordable housing advocates but it remains to be seen if developers will find it financially appealing and if it can generate enough revenue to address NYCHA’s fiscal deficits. In any event, the housing authority needs to regain residents’ trust because failing to reinvest in public housing could be too costly for everyone.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Lease it or lose it? The implications of New York’s Land Lease Initiative for public housing preservation’, in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2zJ06qe

_________________________________

About the author

Shomon Shamsuddin – Tufts University

Shomon Shamsuddin – Tufts University

Shomon Shamsuddin is Assistant Professor of Social Policy at Tufts University. He studies how institutions define social problems and develop policies to address urban poverty and inequality.