Americans who identify with one political party increasingly dislike those in the opposing party – but is this down to political rhetoric, or are there sincere differences between partisans over issues such as social welfare and government spending? In new research, Steven W. Webster examines how people’s policy preferences shape how they view the opposing political party. He finds that when presented with an opposing candidate, members of the other party evaluated them – and their party – more positively if they had less extreme ideological views on social welfare issues.

Americans who identify with one political party increasingly dislike those in the opposing party – but is this down to political rhetoric, or are there sincere differences between partisans over issues such as social welfare and government spending? In new research, Steven W. Webster examines how people’s policy preferences shape how they view the opposing political party. He finds that when presented with an opposing candidate, members of the other party evaluated them – and their party – more positively if they had less extreme ideological views on social welfare issues.

The recent election of Donald Trump as President of the United States laid bare a political reality that has been developing for decades: Americans increasingly dislike the opposing political party, its supporters, and its governing elite. This new style of confrontational and hostile politics – frequently referred to as “negative partisanship” or “affective polarization” – has arisen due to the alignment of partisan identities with cultural, racial, and other social divisions within American society. While these divisions have certainly allowed members of the Democratic and Republican parties to easily see supporters of the opposing party as “the other,” there is also a more rational basis to individuals’ dislike of the opposing political party: Americans have sincere ideological disagreements about policy, especially regarding the proper role of government in dealing with social welfare issues.

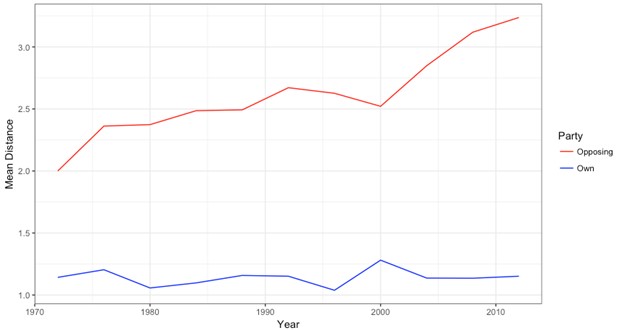

Indeed, data from the American National Election Studies (ANES) suggest that Americans have come to see the opposing political party as ideologically distant from themselves. Utilizing a seven-point measure of ideology that ranges from “very liberal” to “very conservative,” the ANES has consistently asked Americans to indicate their own ideological leanings and their belief about the ideological preferences of the two major political parties. As shown in Figure 1, Americans see little difference between their own ideology and the ideology of their party. However, over the past 45 years, Americans have increasingly come to believe that the opposing political party has ideological preferences that are quite different than their own.

Figure 1 – Mean distance on Liberal-Conservative Scale

Note: Data are from the ANES cumulative data file, 1972-2012

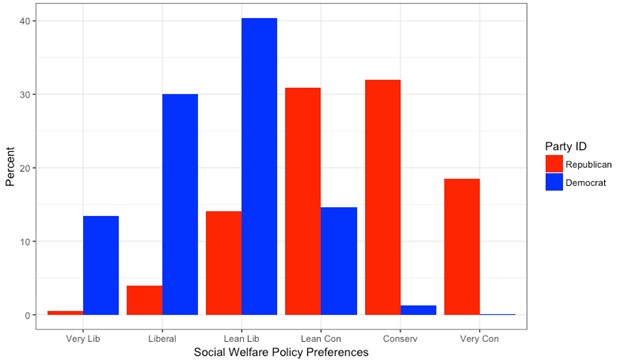

While ideology undoubtedly contributes to how people construct their own identities, there appears to be a rational basis to the trends shown in Figure 1. Combining individuals’ views on government services, government regulation, and federal spending on domestic social programs into an aggregate social welfare scale allows for a straightforward examination of how Democrats and Republicans differ in terms of policy preferences. As shown in Figure 2, approximately 84 percent of Democrats have liberal views on social welfare policy. Republicans, by contrast, hold largely conservative views on social welfare policy: 81.5 percent can be classified as conservative on this scale. Importantly, there are very few Republicans who hold liberal views on the social welfare policy scale (18.5 percent) and even fewer Democrats who have conservative views (16 percent). This partisan division on the social welfare policy scale indicates a considerable degree of partisan-ideological polarization.

Figure 2 – Polarization in the 2012 electorate

Note: Data are from the 2012 ANES.

These differences in social welfare policy preferences play an important role in shaping how Americans view the opposing political party. To illustrate how these policy preferences lead to affective polarization, I conducted an experiment on 3,200 registered voters recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform. Individuals who participated in this study were asked about their political affiliation and ideological leanings. They were then presented with a biography of a hypothetical candidate running for the US House of Representatives. Participants who identified as a Democrat were told about a Republican candidate, while Republicans were told about a Democratic candidate.

Photo by Jerry Kiesewetter on Unsplash

Every participant was told that this candidate for the House of Representatives was 43 years old and had served three terms as a state legislator. However, some individuals were told that this candidate was relatively moderate in terms of ideology. Thus, Democratic respondents were told that the Republican candidate was moderate-to-liberal on social welfare policies; Republican respondents were told that the Democratic candidate was moderate-to-conservative on social welfare policies. Additionally, another subset of the experiment participants was told that the opposing party’s candidate was an “extreme ideologue.” Accordingly, Democratic respondents were presented with a Republican candidate who was described as being very conservative on social welfare issues; Republican respondents were told that the Democratic Party’s candidate was very liberal on social welfare issues.

After the survey participants were told about these hypothetical candidates, they were asked to rate both the candidate and the opposing party on a “feeling thermometer” scale. Commonly used within political science, feeling thermometers ask individuals to rate a person, group, or policy initiative on some scale (usually 0-100 or 0-10), where higher values indicate a more positive assessment.

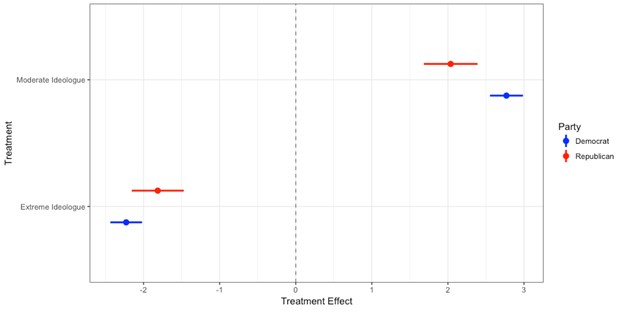

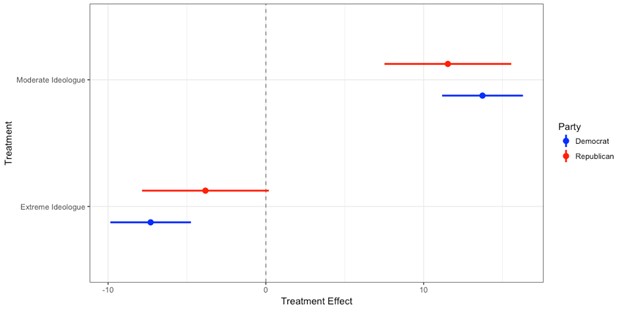

The results of this experiment, shown in Figures 3 & 4, indicate that policy preferences are a cause of affective polarization. Individuals who were presented with a candidate from the opposing party that was described as an “extreme ideologue” evaluated both that candidate and that candidate’s party poorly. Among Democrats, being exposed to a very conservative Republican candidate lowered the ratings of that candidate by 2.23 points (on a 10-point scale) and the Republican Party as a whole by 7.3 points (on a 100-point scale). Likewise, Republicans who were told about a very liberal Democratic candidate lowered their ratings of that candidate by 1.81 points (on a 10-point scale) and the Democratic Party by 3.8 points (on a 100-point scale).

Figure 3 – Affective polarization and political candidates

Note: Data are from a survey experiment fielded by the author in Spring 2016.

Figure 4 – Affective polarization and political parties

Note: Data are from a survey experiment fielded by the author in Spring 2016.

What is particularly noteworthy is that, when partisans were told about candidates from the opposing party who were relatively moderate, evaluations were higher. Democrats who were presented with a moderate Republican rated the candidate 2.77 points higher (on a 10-point scale) and the GOP as a whole 13.7 points higher (on a 100-point scale). Similarly, Republicans who were told about a moderate Democrat rated the candidate 2 points higher (on a 10-point scale) and the Democratic Party 11.5 points higher (on a 100-point scale).

These results indicate that the growing negativity and incivility in contemporary American politics has a logical, rational basis: Americans disagree with each other on important aspects of public policy. Unfortunately, the reality of sharp partisan divisions over policy issues makes the possibility of reconciliation and cooperation between those in opposing partisan camps much less likely. If Democrats and Republicans really had much in common but were nevertheless polarized in opinions due to group-based notions of partisan conflict, then it might be possible to point out the areas of agreement to partisans and reduce the level of animus toward the other side. In this case, getting to better know those on the other side could actually reduce the intensity of partisan conflict. But if in fact we truly disagree on issues, then getting to better know those on the other side of the political divide could end up exacerbating conflict by increasing awareness of deep disagreements over important issues. Rational dislike of the other party may be more difficult to overcome than irrational dislike.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the U.S. Electorate’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics, nor the authors’ institutions.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2jSFV2i

_________________________________

About the author

Steven Webster – Emory University

Steven Webster – Emory University

Steven Webster is a Ph.D. candidate at Emory University. His research interests are in political psychology and voter behavior, with an emphasis on how anger shapes patterns of political behavior and public opinion.

I think “getting along” and really collaborating with one another politically or privately, are two different things.

I have family who are republican, and as long as we don’t talk about anything, we “get along”. But if they feel the need to tell me their deeply held beliefs that they just heard from television, even if it hurts me deeply as a person, because it would limit my ability to live my life well, it’s too hard to put my interests aside and be nice to someone who is against all my goals and beliefs by proxy. That’s what it comes down to, the pre-packaged rhetoric on tv always makes “democrats” or “republicans” the enemy and the more closely your opinions track with tv opinions, the more you are putting your faith, belief and support in strangers on TV and not the people who have gone out of their way to support you, sometimes emotionally, financially and physically, if you happen to be an old and sick bitter republican, advocating to cut off the health care of your own care giver.