Few cities remain static – as years pass, their populations and economic fortunes rise and fall. Maxwell Hartt studied change in the largest 100 US cities over 30 years, finding that most had an overall increase or fall in population rather than experiencing a cyclical boom or bust, and that their economic fortunes were often the opposite of that of their populations’.

Few cities remain static – as years pass, their populations and economic fortunes rise and fall. Maxwell Hartt studied change in the largest 100 US cities over 30 years, finding that most had an overall increase or fall in population rather than experiencing a cyclical boom or bust, and that their economic fortunes were often the opposite of that of their populations’.

I love returning to a city after a long period of time. It never ceases to amaze me. Although I can never decide what is eerier – that time warp feeling when a place is exactly the same as decades earlier or when it has changed beyond recognition. I can still remember my grandfather’s astonishment when he returned to Seoul 50 years after having fought in the Korean War. He simply could not believe his eyes. Similarly, it boggles my mind that my sleepy, slightly derelict hometown of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia is now being heralded as one of Canada’s hippest neighborhoods. How on earth did that happen? How do cities change over time? Do they follow cycles of boom and bust? And is bigger always better?

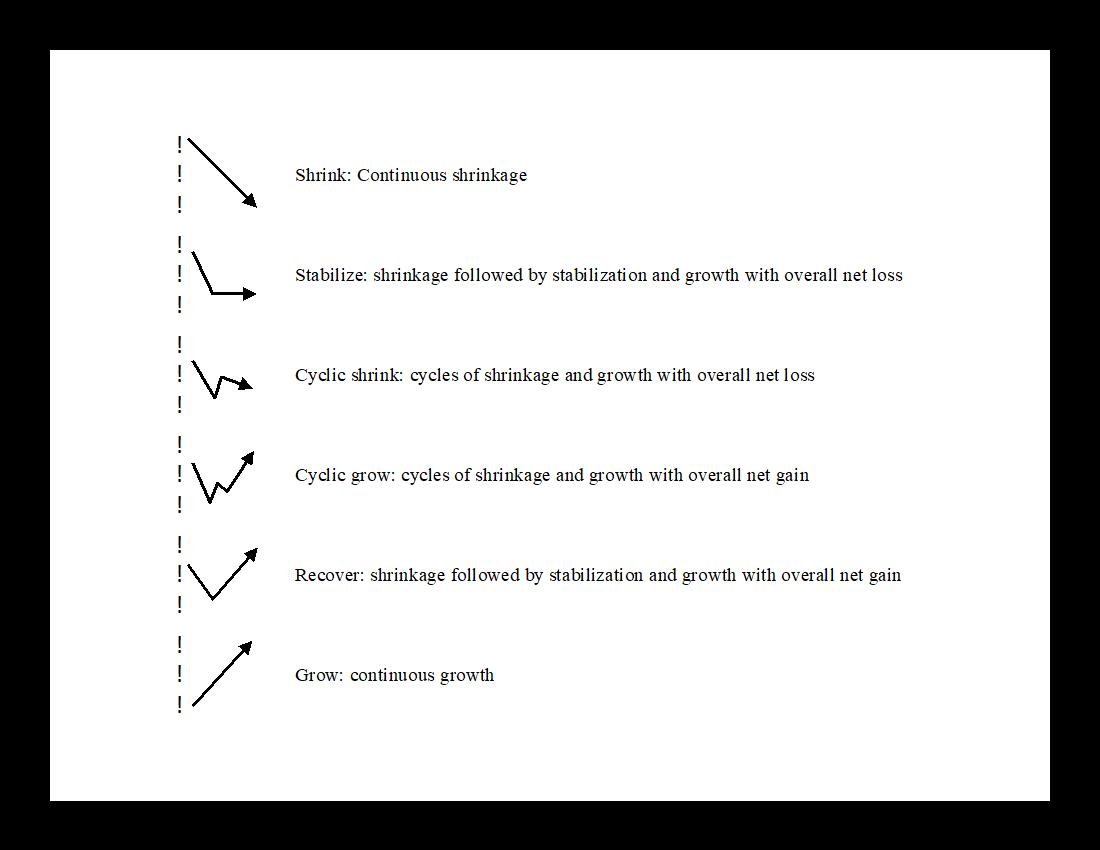

Generally speaking, the trajectory of a city can be categorized in one of six ways:

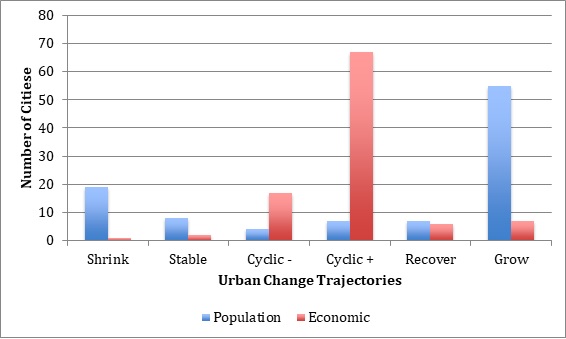

When we look at the 100 largest American cities from 1980 to 2010 (Figure 1), we can see that the population of the majority of cities either shrank or grew continuously. Very few (only 11) had cyclical trajectories. This supports the hypothesis that shrinkage is no longer a temporary stage of a cyclical boom and bust process. In the globalized economy of winner-take-all urbanism, the growing continue to grow and the shrinking continue to shrink.

“DSCF8527” by Chilanga Cement” is licensed under CC BY 2.0

But population is not the only factor determining how cities change. If we consider per capita income as a proxy for economic change, the trajectories of the 100 largest US cities look extremely different. Instead of continuous growth and shrinkage, Figure 1 shows that, economically, almost all of the cities fluctuated. So although bigger is often considered better, population growth is not synonymous with economic growth. And, contrary to popular belief, cities that have lost population may not have declined economically.

Figure 1 – 1980-2010 population and economic trajectories of the 100 largest US cities

Source: US Census and American Community Surveys 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010

In fact, the divergence between population and economic trajectories was especially prominent in shrinking cities. Looking closer at the 20 largest cities to experience an absolute loss of population between 1980 and 2010, Table 1 shows that only one city (Memphis) experienced the same population and economic trend! The majority (12 of 20 cities) experienced overall population decline while per capita income simultaneously grew. New Orleans exemplified the potential disconnect between economic and population trajectories with per capita income growth and population loss in every decade. The stark divergence we see in New Orleans also demonstrates the complexity of shrinkage and the need for in depth context-specific analysis. Despite its many charms, few would argue that New Orleans is a utopian paradise free of economic or societal challenges.

Table 1 – Population and economic trajectories of 20 largest US shrinking cities

| City | Population Trajectory | Economic Trajectory |

|---|---|---|

| Detroit, MI | Shrink | Cyclic - |

| Milwaukee, WI | Shrink | Cyclic - |

| Cleveland, OH | Shrink | Cyclic - |

| Toledo, OH | Shrink | Cyclic - |

| Baltimore, MD | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| St. Louis, MO | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| Cincinnati, OH | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| Buffalo, NY | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| Birmingham, AL | Shrink | Cyclic + |

| New Orleans, LA | Shrink | Grow |

| Philadelphia, PA | Stable | Cyclic + |

| Newark, NJ | Stable | Cyclic + |

| Atlanta, GA | Stable | Cyclic + |

| Washington, DC | Stable | Grow |

| Chicago, IL | Cyclic - | Cyclic + |

| Memphis, TN | Cyclic + | Cyclic + |

| Denver, CO | Recover | Cyclic + |

| Kansas City, MO | Recover | Cyclic + |

| Minneapolis, MN | Recover | Cyclic + |

Source: US Census and American Community Surveys 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010

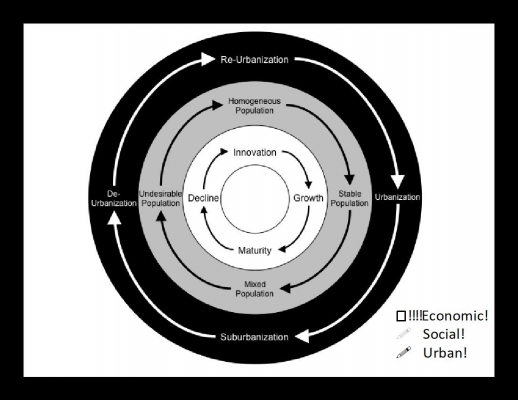

The notion that (1) population trajectories are not cyclical, and (2) economic and demographic trajectories are not inherently synced runs counter to many early economic, urban and social theories of urban growth and decline. Traditionally, urban change has been viewed as a natural cyclical process where growth and prosperity follow shrinkage and decline, and vice versa. From Schumpeter’s ideas of “creation destruction” to the Chicago School of Urban Sociology’s neighborhood lifecycle, cyclical conceptualizations of urban change have been extremely influential in both academia and in practice. However, the results here suggest that these cyclical, parallel trajectories of population and economic change are no longer the norm. And therefore, we need to re-think how we conceptualize both growth and shrinkage. Many shrinking places may be wonderful, prosperous places to live, and further growth may not be the answer to the ills of some large growing cities. We need to step back, take a wider view of population change, and reconsider many of our fundamental assumptions about urban change and prosperity.

Figure 2 – Economic, social and urban theories of urban change

As for my own travels and personal fascination with urban change, I think that it is safe to say that due to its global status, Seoul will probably continue to attract migrants and grow in population. If my grandfather were able to visit it again in another 50 years, I’m sure he’d probably be amazed once again. And as for my hometown of Dartmouth, it’s doubtful that its population will grow much due to its location far from any major metros. But its renaissance may very well continue. Which will be a pleasant, and strange, experience for me to look forward to each time I head home for the holidays.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The diversity of North American shrinking cities’ in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2DXF4mu

_________________________________

About the author

Maxwell Hartt – University of Toronto

Maxwell Hartt – University of Toronto

Maxwell Hartt, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Geography & Planning at the University of Toronto. He is interested in the intersection of demographic change and urban planning; specifically his research focuses on the evolution, complexity and responses to shrinking and aging cities. He is a former Fulbright Scholar and holds a Ph.D. in Planning from the University of Waterloo.