Since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), millions of low-income Americans have gained access to publicly funded health insurance. Yet, the American states have remained critical stakeholders in the Trump era for fighting persistently high levels of inequality in access to health care. Using data from the fifty states, Ling Zhu examines trends in market-based health care inequality in the past two decades, and finds that health care inequalities are greater the more racially diverse a state, and smaller in states with higher levels of social capital.

Since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), millions of low-income Americans have gained access to publicly funded health insurance. Yet, the American states have remained critical stakeholders in the Trump era for fighting persistently high levels of inequality in access to health care. Using data from the fifty states, Ling Zhu examines trends in market-based health care inequality in the past two decades, and finds that health care inequalities are greater the more racially diverse a state, and smaller in states with higher levels of social capital.

Inequality in Private Health Care Coverage

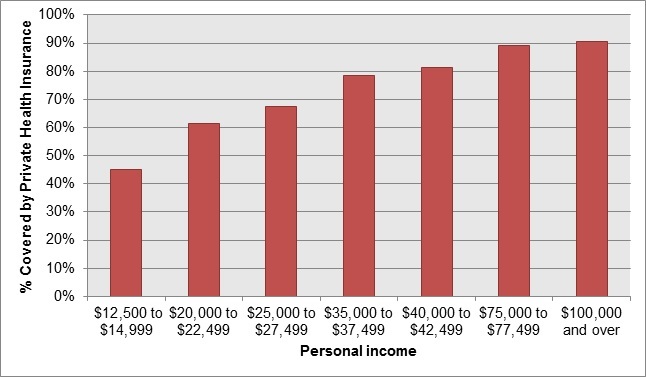

The American health care system is a “hybrid” system, whereby public and private providers exist alongside one another. More than fifty percent of non-elderly Americans obtain their health insurance coverage through private sources, either being sponsored by their employers, or by purchasing privately. As such, private market-based health insurance coverage varies substantially depending on people’s incomes. As Figure 1 shows, at the national level, market-based private health care coverage increases substantially as personal income increases.

Figure 1 – Private Health Insurance Coverage by Selected Personal Income Levels in 2016

Data: U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Surveys

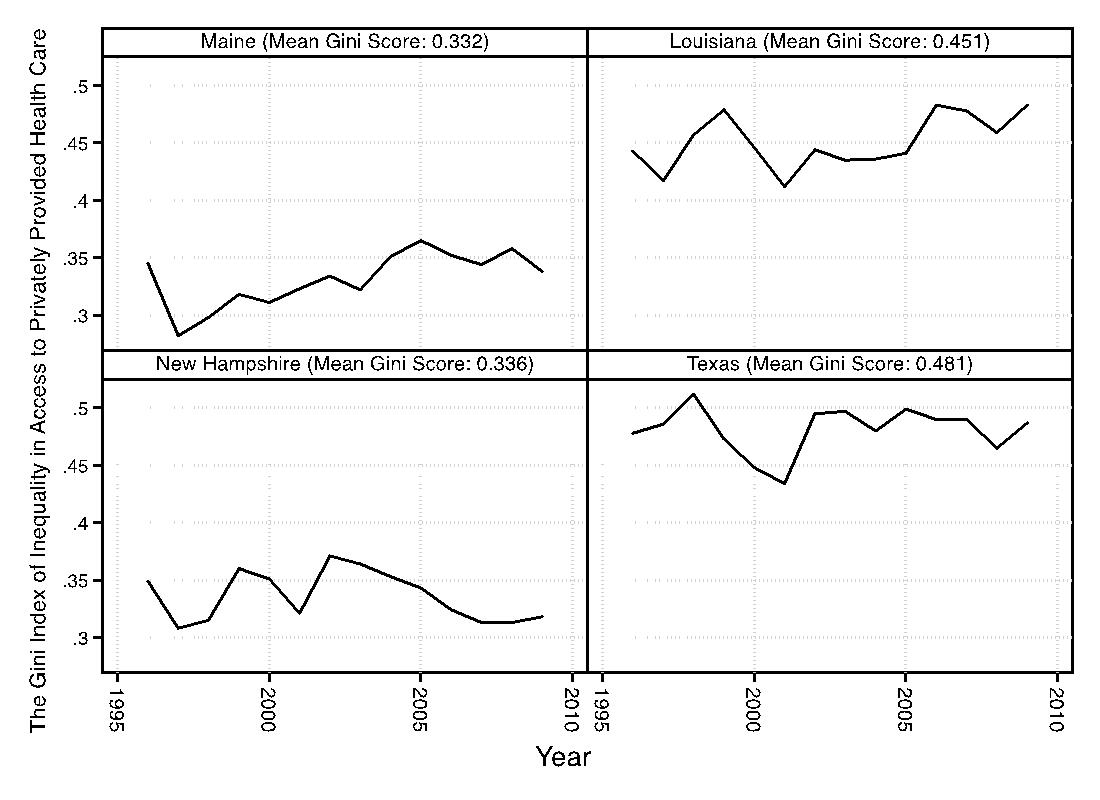

We can also see income-based health care inequality at the state level. For example, as Figure 2 shows, in Texas, the private health insurance coverage rate for those with family income of at least $75,000 (group 9) was substantially higher than that for those with family income less than $5,000 (group 1). Using a Gini-coefficient measure of inequality, we can further assess the unequal distribution of private insurance coverage by income groups. Figure 3 shows how income-based inequality in private health care coverage varies across time and states with four state examples. The two tiles on the left plot the Gini-coefficient of health care inequality in Maine and New Hampshire from 1996 to 2009. These two states represent the scenario of a low level of inequality (bottom 10 percentile among all states). The two tiles on the right plot the Gini-coefficient of health care inequality in Louisiana and Texas, which have very high level of inequality (top 10 percentile among all states).

Figure 2 – Distribution of Private Health Insurance Coverage across Nine Family Income Levels in Texas 2007

Data are based on the U.S. Census Bureau 2008 Current Population Surveys

Figure 3 – Weighted Gini-Coefficient of Inequality in Market-Based Health Care Coverage Based on Nine Family Income Groups: Comparing State Examples from 1996 to 2009.

Social Capital, Racial Diversity and Health Care Inequality

Using data on the fifty American states from 1996 to 2009, I find that both social capital and racial diversity of state populations are important social contexts for understanding income-based health care inequality.

Racial Diversity and Health Care Inequality. In America, race continues to be a determinant of unequal treatment across society. Both market-generated incomes and poverty are unequally distributed across racial groups. This market-based economic inequality is further reflected in health care, as the existing literature concludes that income inequality has a strong link to health care access and income-based differences in people’s health. Racial diversity also affects health care inequality through the policy making process. Extensive public opinion literature suggests racial prejudice coincides with a high level of tolerance for market inequalities and low level of support for welfare. And inter-group prejudice and racial-stereotyping might shrink political support for more redistributive social policies.

Social Capital Reduces Health Care Inequality. Social capital is an expansive concept that has received considerable attention in the study of public policy and politics. The concept of social capital has been developed by Robert Putnam’s, Making Democracy Work (1993) and Bowling Alone (2000). Social capital is broadly defined as an asset that is inherent in social relations, trust, and networks. Social bonds and community engagement, according to Putnam, firm the civic foundation of democracies and equalize social gaps in economic and civic realms. The underlying mechanism for the equalizing role of social capital is that social distance between the privileged and the marginalized can be reduced through building inter-group bonds. Civic engagement and volunteerism, meanwhile, promote egalitarian values and enhance governments’ capability in making liberal and inclusive social policies. Moreover, social capital can be linked to more equal allocation of public health care resources and more accessible health insurance coverage. The existing literature suggests states with a lower stock of social capital are unlikely to invest in the provision of social safety net programs in general.

Photo by Paola Chaaya on Unsplash

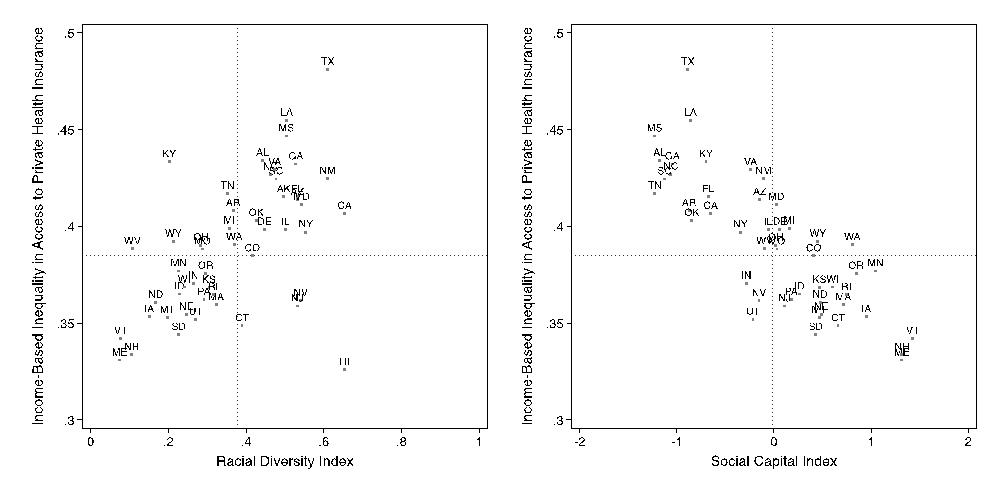

My analysis of the fifty states in a 20-year period suggests that there is a negative relationship between social capital and health care inequality, and conversely, there is a positive relationship between racial diversity and health care inequality. Figure 4 shows a clear-cut pattern with respect to how racial diversity and social capital are correlated with the Gini-coefficient measure of health care inequality. States with racially diverse populations tend to have higher level of health care inequality than states with racially similar populations. The only exception is Hawaii. This is because, for more than 20 years, Hawaii has been a leading state in the effort of pushing forward universal health care reform. Overall, racial diversity is positively correlated with inequality in access to health care. Conversely, social capital is negatively correlated with the Gini-index of health care inequality. States with low level of social capital have higher level of health care inequality than states with high level of social capital.

Figure 4 – The Association between Social Capital, Racial Diversity, and Income-Based Health Care Inequality

Reducing Health Care Inequality in the Diverse American Society

High and persisting levels of inequality in private health care coverage can be deemed as a form of market failure. My analysis suggests that employment-based healthcare insurance and the private insurance markets discriminate against individuals based on their income. Over the past two decades, inequality in health care has been persistent and some states have experienced steady increases in the unequal distribution of health care resources. The key to understanding how democracies attempt to address issues of inequality lies in a complex set of social and political factors. My research suggests both social capital and racial diversity are critical forces that affect health care inequality at the state level. Social capital has a direct and negative impact on inequality in health care.

As the American states continue to play a critical role in reforming and improving the health care system, it is imperative to strengthen the community foundation for promoting more equal health care access. Moreover, the story about how racial diversity might elevate inequality in health care highlights the importance of overcoming the racial gradient in the American society. Many states have experienced rapid demographic changes in the past ten years, particularly the growth of Latino and immigrant populations. As many states become racially more diverse, dealing with racial disparities in health care has become one of the most pressing tasks for making social equity policies which are effective.

- This article is based on the paper, ““Healing Alone?”: Social Capital, Racial Diversity and Health Care Inequality in the American States”, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2DxbA2i

_________________________________

About the author

Ling Zhu – University of Houston

Ling Zhu – University of Houston

Ling Zhu is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston. Her research interests include public management, health disparities, social equity in healthcare access, and the implementation of public health policies at the state and local level.