Partisan polarization has steadily increased in recent decades, culminating in record highs in recent years. In new research, Jamie Carson and Ryan Williamson compare the ideology of winning and losing candidates in US House elections between 1992 and 2012. They find that winning candidates are much less ideologically extreme than those who lose elections. Though some districts prefer more extreme representatives, these are a minority. Together, these findings show that if challengers were more skilled at winning elections, polarization in Congress might be even greater than it is now.

Partisan polarization has steadily increased in recent decades, culminating in record highs in recent years. In new research, Jamie Carson and Ryan Williamson compare the ideology of winning and losing candidates in US House elections between 1992 and 2012. They find that winning candidates are much less ideologically extreme than those who lose elections. Though some districts prefer more extreme representatives, these are a minority. Together, these findings show that if challengers were more skilled at winning elections, polarization in Congress might be even greater than it is now.

Candidate ideology and electoral success

Numerous factors influence which candidate will win a seat in Congress; partisanship, spending, and prior experience are some of the strongest predictors of electoral outcomes. However, how ideologically extreme a candidate is may also have an effect. We used the Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections published by Adam Bonica to obtain measures of each candidate’s ideology. We then transformed that measure to create a scale of extremism. More moderate candidates are closer to 0, and higher values represent more extreme ideologies.

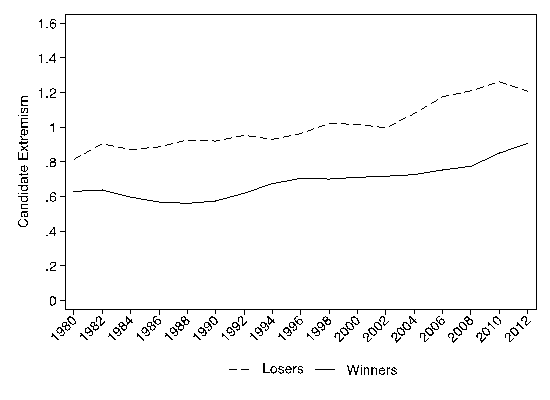

The figure below shows a clear ideological difference between winning candidates and their losing counterparts in US House elections since 1980. Although both have been gradually increasing over time, winning candidates are considerably more moderate than those who lose their bids for a seat in the House of Representatives.

Figure 1—Average Extremism for Winning and Losing Candidates

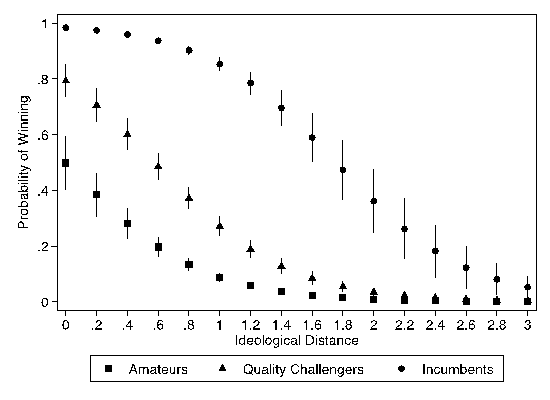

We find that this detrimental effect exists even after accounting for things like candidate partisanship, experience, and relative spending. This relationship is shown in the figure below.

Figure 2—Predicted Candidate Success by Ideological Distance

The vertical axis shows a candidate’s probability of winning an election, and higher values indicate greater chances of success. The horizontal axis shows the distance between the ideology of a district and a candidate. Perfect agreement between the two is represented by 0, and larger values denote less agreement. Incumbents are represented by the circles, quality challengers (those who have previously held some form of elected office like state legislator or mayor) are represented by triangles, and those who have never served in elective office (amateurs) are represented by squares. Consistent with what is already known about House elections, incumbents are more likely to succeed than other candidates. However, even incumbents who are too inconsistent with the districts they hope to represent have the same probability of success as candidate who have never held office before but is closer to the district’s ideological preferences.

Ideology of the constituency matters

There are noticeable exceptions to this dynamic, but these differences can be reconciled when we also consider the ideology of districts as well. We divide districts into four categories based on their ideology. In the most moderate of districts, increased extremism is punished more severely than in any other district. Conversely, in the most extreme districts, candidates are not punished for being similarly extreme. However, it should also be noted that being moderate does not negatively hurt a candidate’s chances of success either. In between these two poles, extreme candidates are less likely to succeed in their pursuit of a congressional seat, but their chances are greater than in the most moderate districts.

Photo by Jomar Thomas on Unsplash

In short, being relatively moderate does not seem to hurt a candidate’s chances of winning office in any district. But being more extreme will have negative effects except for in similarly extreme districts (and those only make up about 23 percent of congressional districts in our dataset).

Things could be worse

These results lead us to believe that polarization could be worse if relatively moderate candidates were not as effective at winning seats in the House. This also means that challengers attempting to outflank incumbent members in primary elections by positioning themselves as the true “conservative” or “liberal” may prove counterproductive during the general election, which is consistent with other work in this area.

Therefore, as the 2018 midterm elections near, keeping an eye on how candidates position themselves will be informative. As national conditions increasingly favor the Democratic Party, their ability to regain control of the House of Representatives may depend on not overplaying their hand in most districts, especially in races against less conservative Republicans.

- This article is based on the paper “Candidate Ideology and Electoral Success in Congressional Elections” in Public Choice.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2nxKvRH

_________________________________

About the authors

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie Carson is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at The University of Georgia. His primary research interests are in American politics and political institutions, with an emphasis on representation and strategic political behavior. Most of his current research focuses on congressional politics and elections, American political development, and separation of powers.

Ryan D. Williamson

Ryan D. Williamson

For the 2017-2018 academic year, Ryan will be working on Capitol Hill as a member of the American Political Science Association’s Congressional Fellowship Program. He will be joining Auburn University’s Department of Political Science as an assistant professor starting the fall semester of 2018. His interests include Congress and Legislative Procedure, Congressional Elections, Institutional Development, the U.S. Presidency, and Research Design and Methods.