Despite the intent of the Framers of the US Constitution that the US Senate would be a place for measured deliberation, it has now become nearly as partisan and gridlocked as the US House of Representatives. In new research, Jeremy Gelman finds that party members in the Senate are more likely to vote with their party when they believe the majority party will lose power in the next elections. The rise of insecure majorities in the Senate, he writes, means that partisan agendas and a lack of compromise are here to stay.

Despite the intent of the Framers of the US Constitution that the US Senate would be a place for measured deliberation, it has now become nearly as partisan and gridlocked as the US House of Representatives. In new research, Jeremy Gelman finds that party members in the Senate are more likely to vote with their party when they believe the majority party will lose power in the next elections. The rise of insecure majorities in the Senate, he writes, means that partisan agendas and a lack of compromise are here to stay.

For many longtime observers, the United States Senate is broken. Originally fashioned to be the ‘saucer that cools the hot tea’ of the more temperamental House of Representatives, the contemporary Senate rarely upholds its aspirational status as a bipartisan, deliberative body. Instead, today’s Senate is marked by brutal partisan politics. Both Democrats and Republicans have seemingly given up on bipartisan compromise and opted to push their party’s agenda at any cost. While this partisan animus may now seem normal, the Senate has not always been this way. Rather, it fluctuates between eras of partisan rancor and bipartisan compromise. What explains these shifts between conflict and comity?

In new research I find that political parties in the Senate are more likely to vote along party lines when they believe the current majority party is likely to lose power in the next few elections. This idea, which Frances Lee dubs ‘insecure majority status,’ pushes parties to uncompromising stances. The majority party, who might be on its way out, tries to pass as much partisan legislation while it can. The minority party chooses to avoid compromise and wait, hoping it will soon control the Senate and advance its own agenda. Notably, insecure majority status has become the norm in the Senate. The intense, sustained competition to control the chamber over the past 40 years – an unusually long time – has exacerbated the trend towards partisan voting.

Winning is everything in the Senate but stability fosters compromise

While we may hope the goal of Senate parties is to pass new effective laws, in reality, Democrats and Republicans are driven by their goals of winning and maintaining majority status. In a revealing comment, then-Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-TN) noted [subscription needed] that “[m]aintaining our majority is our top priority in many ways. Secondly, it’s our responsibility to govern.” Of course, how difficult it will be for Democrats or Republicans to win control of the chamber changes each election cycle. Yet, when the current majority party might lose its power, partisan conflict between Democrats and Republicans is likely to increase. The reason is straightforward: more competition to win decreases each party’s willingness to compromise in the short-term.

Take the current Senate as an example. Even with Republicans’ favorable 2018 map, majority status is very insecure. In nearly every election cycle, either party can win the majority of seats. This uncertainly compels the majority to advance a partisan agenda instead of trying to negotiate compromises. Doing so helps the party push its policies while it can and shows voters it has popular ideas. The Republican agenda this current Congress exemplifies this strategy. The three major issues Republicans have tackled – ending Obamacare, cutting taxes, and confirming Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court – have all been pursued in a partisan manner with no thought towards compromise.

Similarly, Democrats have shown no interest in working across the aisle. Their unified opposition makes sense. Even if they do not win the majority in 2018, Democrats reasonably believe they can win back control in 2020. In their view, why should they compromise now if they are patient and can pass more liberal ideas in a few years?

“Subway to US Capitol” by Greg Palmer is licensed under CC BY 2.0

While this competitive environment describes the contemporary Senate, this has not always been true. Democratic majorities in the 1940s and 60s were remarkably secure. In a more secure, less competitive environment, both parties have incentives to compromise. The majority, not needing to furiously pursue its partisan goals before an election, can be more patient in passing its agenda. The minority, knowing obstinate opposition will not help it win the majority, must work with the other party to pass any of its policy ideas. Put simply, stability fosters compromise.

Measuring the security of a Senate majority

My research examines this relationship between insecure majority status and party voting in the Senate over the past century. What makes this question particularly interesting is how Senate elections work. Every two years, only one-third of the Senate is up for reelection. As a result, a majority’s security is not just based on its seat share in the Senate, but how many of its members are up for reelection and the relative security of each of those seats. Being the case, my measure of a majority’s security involves three steps to take these factors into account.

First, using presidential vote in the past two elections, I calculate the probability the majority party wins a given Senate race. Second, using those individual seat probabilities, I calculate the probability the majority party wins enough seats to maintain its majorities. Finally, I use these election year probabilities to calculate the three-term (six year) running average of a majority party’s prospects for remaining in control of the Senate.

The running average captures the broader environment of insecurity the parties perceive. If, by happenstance, the majority has a very favorable map in the next election, as Republicans do in 2018, it does not mean the majority is necessarily secure. Senator leaders’ time horizons can extend beyond a single election cycle as they wait for the day power eventually changes hands. In many ways, this is the calculus we see in the current Senate, where Democrats face a difficult 2018 electoral environment but a much more favorable one in 2020.

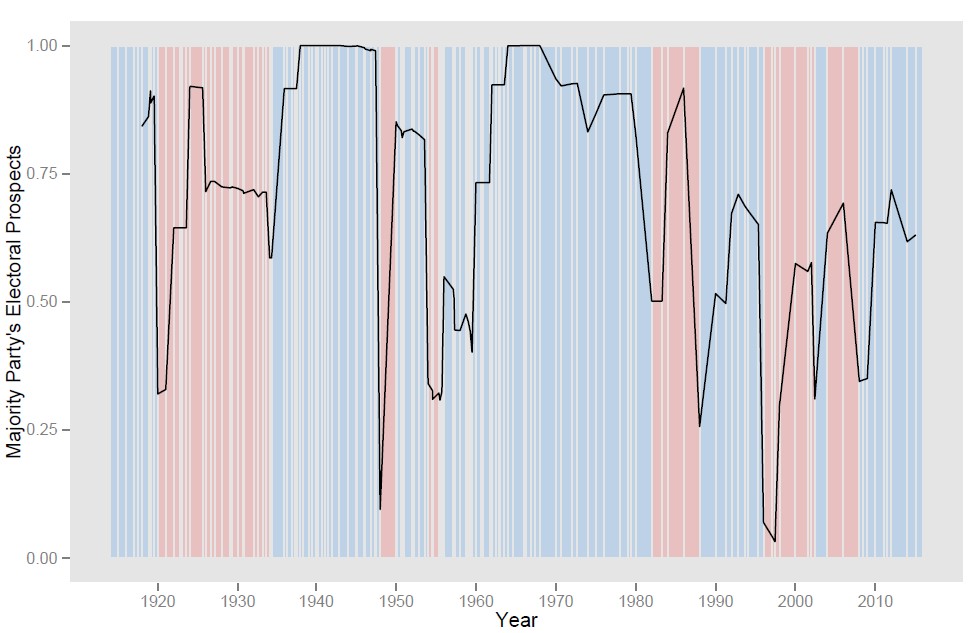

Figure 1 – Probability majority party retains control of the Senate

Note: This measure is the three-term rolling average of the probability that the majority party currently in power would retain majority status in the Senate. Blue shading indicates a Democratic majority and red shading indicates a Republican majority.

As Figure 1 shows, these modern insecure majorities have only existed for the past few decades. Early in the 20th century, majority status was less secure but the rise of the Democrats’ New Deal Coalition led to a prolonged period of secure majorities in the Senate. However, since the 1980s, competition to control the Senate has substantially increased.

Insecure majorities mean there is little compromise

The rise and fall, and rise again, of insecure majorities has a durable association with party voting. Compared to a more secure environment, the partisan split on a roll call vote in an insecure environment increases 12 percent. More concretely, when competition to control the Senate is high, an average vote attracts between 4 and 8 fewer minority party Senators relative to when the majority is almost certain to remain in power.

One of the recurring themes of this congressional term is Senate Republicans’ inability to attract enough Democratic votes to pass important legislation. Certainly a number of factors, such as polarization and President Trump’s unpopularity, contribute to this dynamic. But my research suggests that the Republicans’ tenuous long-term hold on their majority also plays a role. Even if Democrats do not flip the chamber in 2018, they believe they can win back control of the Senate in 2020. As a result, they are not cooperating with Republicans and the Republicans are pushing a partisan agenda Democrats will not agree to.

This dynamic of insecure majority status is unlikely to go away any time soon. Unlike the old textbook congresses of the 1960s that featured a dominant Democratic Party, Democrats and Republicans compete with one another for control of the Senate at near parity today. Consequently, we should not expect the bitter partisan battles in the Senate to abate in the near future.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘In pursuit of power: Competition for majority status and Senate partisanship’, in Party Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2DI3e2V

About the author

Jeremy Gelman – University of Nevada, Reno

Jeremy Gelman – University of Nevada, Reno

Jeremy Gelman is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Reno. His research examines congressional agenda-setting, messaging politics, and US presidential-legislative relations. His work has appeared in Party Politics and Legislative Studies Quarterly.