On paper the 2018 Mexican presidential election should benefit from recent reforms that sought to improve electoral conditions. But the reality of campaigns awash with dark money, widespread vote buying, toothless electoral institutions, weak democratic processes within parties, and independents that aren’t very independent suggests that little has really changed, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

On paper the 2018 Mexican presidential election should benefit from recent reforms that sought to improve electoral conditions. But the reality of campaigns awash with dark money, widespread vote buying, toothless electoral institutions, weak democratic processes within parties, and independents that aren’t very independent suggests that little has really changed, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

On 1 July 2018, Mexicans will head to the polls to vote in the first general election since an ambitious political and electoral reform was signed into law in February 2014.

The law, which attracted broad cross-party support, aimed to address some of the numerous grievances that had plagued the Mexican electoral process since the transition from de facto one-party rule in 2000 by enabling reelection for legislators, tightening up campaign spending rules, and allowing parties to form coalitions.

In recent years there have been growing demands for reform in Mexico (Carlos Adampol Galindo, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although not technically part of the reform itself, a constitutional amendment to allow independent candidates to run for office was passed a few months earlier (September 2013). To oversee the changes, a new and beefed-up electoral authority, the Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE), was created. At least on paper, it would seem that Mexican elections were finally on track to be not just free, but for the first time actually fair.

But as the 2018 political campaign nears the finish line, it seems that by most measurable outcomes the reform has failed to live up to expectations. Worst still, it also appears that Mexicans’ confidence in their electoral institutions, namely the INE, is at an all-time low.

What went wrong? And why has it proven nearly impossible to break the stranglehold of the so-called Mexican “partidocracy” on the political establishment?

The revolving door

Mexico’s political establishment has largely been viewed as a revolving door, with adherence to party ideologies running only skin-deep. When one’s political career stagnates in one party, it’s time to jump ship.

José Antonio Meade, a long-serving technocrat who held ministerial positions in the last PAN government, became the candidate of the ruling PRI, largely because the party could not find someone both popular and untainted by corruption allegations. Meanwhile, the right-wing PAN is benefitting from the new provisions for coalitions by allying with the left-wing PRD, a political marriage that seems completely contradictory given the former’s labelling of the PRD’s past policies as “populist” and the PRD’s continual criticism of PAN’s “neoliberal” ideology.

The more hardline left-wing Morena, led by Andrés Manuel López Obrador in his third bid for the presidency, is perhaps the most glaring offender. He has described his rivals as the “mafia in power” yet happily welcomed disgruntled former PRI and PRD members into his ranks. These include disgraced former Mexico City mayor Marcolo Ebrard, as well as a former union leader accused of corruption, Napoleón Gómez Urrutia.

López Obrador’s claim to be the only true anti-establishment candidate also seems puzzling considering that he has been a career party politician, serving under the PRI into the late 1980s, and later the PRD until 2012.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador addresses a really in Ecatepec (detail of Mario Delgado Carrillo, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Then there are the independents, none of whom came from grassroots or civil-society organisations, NGOs, or left their parties long enough ago to claim true independence.

Former first lady Margarita Zavala left PAN once it became clear that Ricardo Anaya would muscle himself into the party’s candidacy despite trailing her in opinion polls. Jaime “El Bronco” Rodríguez was a PRI stalwart until he made his bid for governor of Nuevo León in 2015.

In Mexican politics, only the colours change, but the faces stay the same.

The hope of the independents

Hopes that the presidential race could be disrupted by an independent candidate have also been dashed.

For starters, the requirements for independents proved extraordinarily steep. One per cent of signatures from the nationwide electoral registry amounts to around 866,000: this is roughly the same number needed in the US, a country with nearly three times the population.

Of the five independent aspirants, only two could claim to be truly independent: a female indigenous leader and a former broadcaster, but both failed to make the cut. This left just three, all of whom were former party members. Of the three, two were later disqualified by the INE for having used hundreds of thousands of fake signatures.

In a late twist that was lambasted by civil society, Mexico’s electoral court decided to allow one of these disqualified candidates, “El Bronco”, to run anyway, arguing that a small percentage of the supposedly fake signatures were real and that this was enough for him to hit the target. That thousands of other signatures were faked was apparently of no consequence.

“El Bronco” may be the luckiest loser in Mexican electoral history. He is known best for arriving to his swearing in ceremony as governor on horseback, his colloquial language, and casual misogyny, not to mention outlandish proposals like chopping off criminals’ hands. He is the antithesis of the type of grounded, progressive politician that Mexico sorely needs to wean public support away from the established candidates.

That Mexico’s other independent, Margarita Zavala, is a former first lady goes to show the real meekness of their threat to the political establishment. And Zavala’s decision to quit the race in May also demonstrates that her commitment to fight until the end was never really there.

The primaries that weren’t

One of the changes brought about by an earlier electoral reform in 2007 was to shorten the campaign period to just three months (April-June), although another three-month period was allotted from December to February for primary campaigning. Unfortunately, the major parties decided to turn this into a six-month presidential campaign by having no primary elections at all.

Meade was chosen through a classic PRI “dedazo” – that is, the tradition of Mexican presidents designating their successors as they did under single-party rule. More surprising was the lack of competition within the PAN-PRD coalition, given that there was no shortage of potential candidates.

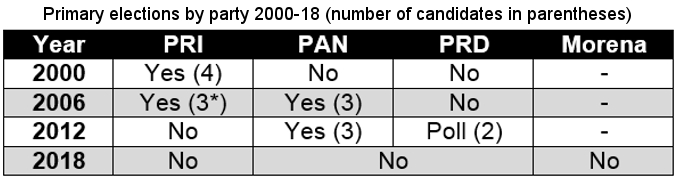

As for Morena, it was a given that López Obrador would be its candidate – the party was founded as a vehicle for his third run at the presidency. But this still represents an overall setback to internal party democracy: in 2012 both the PAN and PRD held some form of internal election, and in 2000 and 2006 even the PRI had a primary.

*PRI pre-candidate Arturo Montiel dropped out of the race in 2006 due to a corruption scandal

There could hardly be a better example of how parties circumvent reforms to maintain Mexico’s traditional style of politics. And this aside from the sheer cynicism of all three main candidates spending three months on the road and wasting millions on TV spots to campaign for primary elections that were in the bag from day one.

Dark money rules

It is a well-known fact that “dark money” – money that isn’t properly accounted for – represents the bulk of party financing for major elections in Mexico. This dark money can come from many sources, including the private sector, criminal gangs, and public funds illegally diverted for electoral purposes, usually to favour incumbents.

A recent analysis of Javier Duarte’s fraud in the state of Veracruz, which was possibly the biggest corruption scandal in Mexican history, showed that as much as $643 million pesos (roughly $45 million dollars) was diverted from Veracruz’s coffers into the campaign of Enrique Peña Nieto in 2012.

Despite a beefed-up INE and other reinforced anti-corruption institutions like the federal auditor, the current election appears to be little different.

A recent report by a local NGO revealed that for every legitimate peso used in electoral financing, another 15.3 pesos is spent in dark money, with an extensive network of shell companies and money-laundering operations helping to channel this money into party coffers.

Not only does this money go unreported, but its electoral use is also illegal: much of it is spent on vote buying, which is endemic throughout the country, whether though doling out simple packs of foodstuffs and household items to those in rural areas or by more sophisticated methods like providing pre-paid debit cards as the PRI did in the 2012 election (for which they went largely unpunished).

By law Mexico’s election campaigns are mostly government-financed, with the aim of preventing powerful private interests from wielding too much influence. But there are still serious doubts about just how committed the INE is to stamping out illegal financing or campaign overspending. Indeed, the notion that the INE would bar any major party from doing either seems almost unthinkable.

It was recently revealed that “El Bronco” had nearly $9 million pesos in undeclared financing and that his total campaign spending was on the verge of exceeding the legal limit. The INE’s fine was little more than a slap on the wrist.

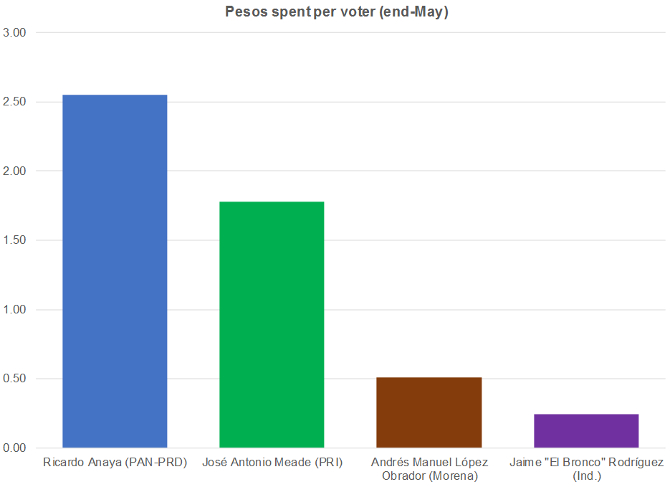

And yet Mexican elections need not be so expensive to be successful. Morena, running without the benefits of incumbency in any state, is spending considerably less than any other party, with total spending of $43.6 million pesos at the end of May, versus $152.9 million for the PRI and $219.2 million for PAN-PRD.

López Obrador may not just win the presidency with the biggest margin of victory in recent history (he is currently polling at over 50%), he might do so while running the most cost-effective campaign in Mexican history as well.

Source: Unidad Técnica de Fiscalización, INE

Chipping away at the establishment

So have electoral reforms worked?

From a purely procedural perspective, they have certainly changed various aspects of Mexican elections that were severely flawed, not least by shortening campaign times and allowing independents to run. But in practical terms, it’s hard to tell the difference between this and any previous Mexican election.

Campaign financing is still raised mostly by illegal means and vote buying is still rampant. Electoral authorities remain unwilling to challenge the worst offenses. Parties still select their candidates by decree of their leaders rather than through the preferences of their rank and file. And the independents aren’t all that independent.

Time will tell if the vices of Mexico’s political establishment can ever be tamed. But as things stand, the 2018 election appears to be business as usual for all involved.

- This article first appeared at the LSE’s Latin America and Carribean blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2KarUVV

About the author

Rodrigo Aguilera

Rodrigo Aguilera

Rodrigo Aguilera is a Mexican-born, London-based economist who has worked as an international economist for Chatham House and the Economist Intelligence Unit, where he was the lead analyst for Mexico from 2012 to 2017 (as well as covering other countries such as Chile, Peru, and Venezuela). Rodrigo holds a BSc in Economics from Universidad de las Américas-Puebla and an MSc in Social Policy and Development from LSE.