What we know about their labour market effects, with an analysis of data on 30 OECD countries over 45 years, write Claudia Olivetti and Barbara Petrongolo.

What we know about their labour market effects, with an analysis of data on 30 OECD countries over 45 years, write Claudia Olivetti and Barbara Petrongolo.

All high-income countries, as well as several developing countries, have policies in place to make it easier for people to balance their working lives with their family commitments. These include parental leave, childcare support and flexible work arrangements, to name just a few. The impact of these policy provisions on the labour market outcomes of parents, and especially mothers, is actively debated in both policy and academic circles.

Proponents of family policies typically emphasise their contribution to gender equality, by enabling women to combine careers and motherhood, and sometimes their beneficial impact on child development. Opponents often warn against consequences of long parental leave and flexible work arrangements, which may be detrimental to women’s careers via both the loss of valuable work experience and possibly the higher costs for employers to hire women of childbearing age.

How do policies and outcomes vary across countries? What works and what doesn’t? In recent work, we draw lessons from existing studies and our own analysis on the impact of parental leave and other forms of family intervention on female employment, earnings gaps and fertility.

At present, all OECD countries with the exception of the United States have in place paid maternity leave rights around the time of birth (of about 20 weeks on average) and much shorter paternity leave rights (typically below two weeks). Following birth-related leave, either parent is entitled to parental leave, with lower income replacement ratios. Parental leave tends to be very long in Nordic countries (14 months in Sweden, 20 months in Norway and nearly three years in Finland), but much shorter or even absent in the rest of Europe.

The introduction of parental leave rights was followed, with long and varying lags, by other family-friendly policies such as public or subsidised childcare, part-time work or flexible working time, and in-work benefits for working parents. The rationale behind these policies was often to encourage fertility while limiting the career penalty of motherhood. Public spending on childcare is currently 0.7 per cent of GDP on average across OECD countries, and between 1-2 per cent in France, New Zealand, Scandinavia and the UK. These countries also have relatively generous family benefits in cash or in-kind and a high proportion of employers offering flexible working time arrangements.

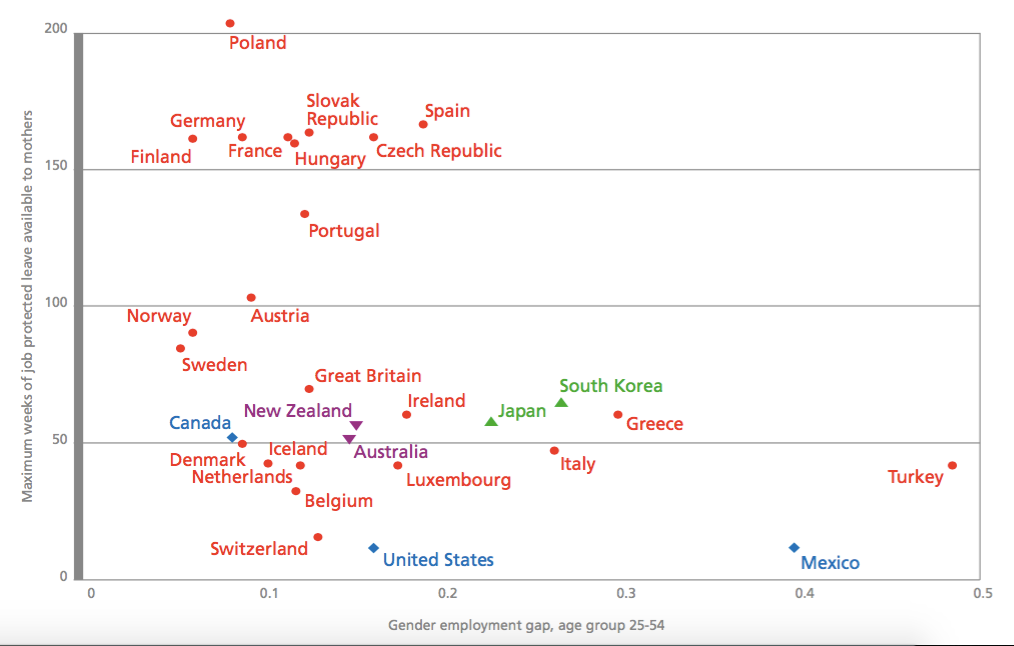

Figure 1 summarises cross-country variation in parental leave available to mothers, and plots it against gender gaps in employment rates. Overall, countries with longer leave entitlements tend to be characterised by narrower employment gaps. Does this mean that more weeks of leave necessarily foster gender equity in the labour market?

Progress in the evaluation of the impact of family policies on labour market outcomes has been challenged by two sets of issues. The first arises from the complexity of modern family legislation. Parental leave can vary in length, job protection, income support and availability to either parent. The generosity of subsidised early years education and care may be means-tested. Other provisions, such as family transfers and tax allowances to low-income workers with children, might also be in place.

The recent introduction of family-friendly practices (right to part-time work, flexible working time) adds further elements to the picture. Clearly, there are interdependencies in the introduction and impact of each of these policies, which are missed by studying them in isolation. The complexity of each single form of intervention also makes it harder to cover the big picture without neglecting relevant details.

The second set of issues concerns the direction of causation and the possibility that there are unobservable influences on both policies and outcomes. For example, a stronger female presence in the labour market raises the demand for interventions that help women to combine work and motherhood. More egalitarian gender roles may also induce both higher female participation and family-friendly legislation.

Figure 1 – Parental leave and employment gaps in OECD countries

Cross-country evidence

One strand of research makes use of the rich variation across countries (or geographical areas within countries) and the availability of internationally consistent data on a variety of labour market outcomes. Ruhm’s (1998) seminal work finds that short periods of parental leave entitlement (around three months) lead to a small rise in employment rates, with little impact on wages. Longer entitlements (of around nine months) lead to a negligible additional impact on employment but sizeable negative effects on wages.

Employment effects can be generated by stronger labour market attachment during job-protected leave and the right of mothers to return to pre-birth jobs. But there are also entitlement effects for women who, though they wouldn’t otherwise participate, intend to accumulate work experience to qualify later for parental leave benefits. Detrimental wage effects after long periods of absence may be driven by loss of actual labour market experience and non-wage costs to firms.

Our research extends the approach of Ruhm (1998) and later work, bringing together data on 30 OECD countries over 45 years, covering gender outcomes in employment and earnings, fertility and the expansion in several dimensions of family policies.

Our findings suggest that job-protected leave entitlements up to a year and a half are associated with better female employment and wage outcomes. This is probably because they allow women to return to their pre-birth job, without having much effect on fertility. But we find that longer and more generously paid entitlements may indeed be detrimental to female employment, especially for the less skilled.

For the college-educated, longer parental leave seems instead to be associated with wider earnings and wage gaps virtually throughout the whole range of leave entitlement variation observed in our sample. The returns to job-specific experience for this group is plausibly higher than for the less skilled; and skilled women have more to lose from missed career advancement opportunities.

The one indicator that is associated with more equal gender outcomes across the board is public spending on early childhood education and care. Presumably, the availability of cheap substitutes to maternal care encourages female labour supply with positive, rather than negative, effects on the accumulation of actual experience.

Cross-country studies provide a rich and suggestive picture. Since they are based on country-level outcomes, they take account of spillover effects of policy beyond the targeted population. But causal inference based on a country-level panel may be delicate whenever policy adoption is itself a response to labour market trends. The need for policy measures that are comparable both internationally and over time reduces the complexity of intervention to relatively coarse indicators.

Policy evaluations with micro data

Another strand of research has addressed these concerns by evaluating the impact of policy for specific countries by combining rich micro data – often social security records – and variation from natural experiments. Studies of Austria, Germany and Norway (respectively, Lalive and Zweimüller, 2009; Schönberg and Ludsteck, 2014; and Dahl et al, 2016) tend to find that parental leave delays mothers’ return to work, with no discernible effects on their employment rates in the long run.

Various factors may explain such discrepancies. First, the beneficial impact of maternity leave may be overestimated in cross-country studies in so far as exogenous shocks to participation induce family-friendly legislation. Second, widespread extensions to leave rights in most countries have inevitably shifted the focus of later studies based on micro data towards variations in parental leave at much longer durations. It might thus be possible that the availability of some job protection, relative to no protection at all, would ensure continuity of employment and discourage transitions out of the labour market, while further extensions would simply delay return to work without further gains in employment. Overall, there is no compelling evidence that extended parental leave rights have a positive impact on female employment.

In several countries, parents returning to work after childbirth continue to receive state support in the form of subsidised or publicly provided childcare and pre-school programmes. For the United States, Cascio and Schanzenbach (2013) find only mild effects of the availability of pre-school (for four year olds) on maternal labour supply, while public subsidies for kindergarten provision, aimed at five year olds, produce clearer employment gains for mothers.

According to Gelbach (2002), hours and employment gains mostly accrue to single mothers, with lesser effects detected for married mothers. Similarly, Lefebvre et al (2008) detect a sizeable impact of childcare subsidies for four year olds in Quebec, when combined with wider availability and high quality of service.

In contrast, Havnes and Mogstad (2011) detect only tiny maternal employment effects of subsidised childcare in Norway, following a large-scale expansion in public childcare in 1975. Givord and Marbot (2015) draw similar conclusions for France, where an average 50 per cent subsidy to childcare spending only raised female participation by one percentage point.

Besides crowding-out other forms of childcare, limited effects of subsidies are not surprising in a context with relatively high female participation and low childcare costs at baseline. Bettendorf et et al (2015) and Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas (2015) detect slightly stronger effects for the Netherlands and Spain, respectively.

Conclusion

In summary, while no obvious consensus on the labour market impact of parental leave rights and benefits emerges from the body of empirical research, both macroeconomic and microeconomic research tend to find positive effects of subsidised childcare on female employment, although once more, gains appear more moderate based on micro-level evidence.

The micro-level studies also find beneficial effects of in-work benefits on female employment, although these are typically sizeable only for single mothers. A potential common theme of our findings is that making it easier to be a working mother may matter more than the length of leave entitlements or the payments that new parents receive while out of the labour force.

- This blog post appeared originally on CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and at the LSE Business Review blog. It is based on the authors’ paper The Economic Consequences of Family Policies:

Drawing Lessons from a Century of Legislation across OECD Countries, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31: 2015-230 (earlier version available as CEP Discussion Paper No. 1464).

- Featured image credit: DesignRaphael Ltd for CentrePiece magazine, not under Creative Commons. All rights reserved.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2PWOkgT

About the authors

Claudia Olivetti – Boston College

Claudia Olivetti – Boston College

Claudia Olivetti is a professor of economics at Boston College.

Barbara Petrongolo – Queen Mary University

Barbara Petrongolo – Queen Mary University

Barbara Petrongolo is professor of economics at Queen Mary University, director of the CEPR labour economics programme and research associate at the Centre for Economic Performance of the LSE. Her main area of interest is labour economics. She has worked extensively on the performance of labour markets with job search frictions, with applications to unemployment dynamics, welfare policy and interdependencies across local labour markets. She has also carried out research on the causes and characteristics of gender inequalities in labour market outcomes, in a historical perspective and across countries, with emphasis on the role of employment selection mechanisms, structural transformation, and interactions within the household.