In a majority of US states, voters can influence policy via ballot measure, which in some cases can include tax increases to fund new initiatives. But how can those who support these policies overcome voters’ resistance to new taxes? Travis Braidwood finds that the answer may be a simple one: if the language on a ballot initiative is made more specific and provides details of how new taxes will be used, voters will be more likely to support the measure.

In a majority of US states, voters can influence policy via ballot measure, which in some cases can include tax increases to fund new initiatives. But how can those who support these policies overcome voters’ resistance to new taxes? Travis Braidwood finds that the answer may be a simple one: if the language on a ballot initiative is made more specific and provides details of how new taxes will be used, voters will be more likely to support the measure.

Last year, 38 states had more than 160 ballot measures up for consideration by voters. Given the pervasiveness of ballot measures, it comes as no surprise that there has been considerable research surrounding ballot propositions.

What is still relatively unexplored is the intersection of ballot and taxation literatures, namely, the role of language in altering support for ballot measures calling for a new tax to support a new policy – also known as an exaction – and how the ballot’s messaging affects voter interest and strength of support. By relying on original experimental data, I sought to extend existing research by analyzing changes in ballot language for measures which require new taxes.

Citizens are hesitant to fund government projects when there is uncertainty regarding waste, and are definitely loathe to pay new taxes. I argue that providing greater details regarding how their tax dollars will be spent will increase voter confidence and strengthen voter opinions about the ballot issue. To test this proposition, I conducted a series of experiments where participants were randomly assigned ballot measures that require voters to pay a tax in exchange for a government service with varying levels of language specificity.

Two experiments to explore how ballot measures are framed

I conducted two experiments. The first was in the fall of 2012 at Florida State University (FSU) amongst students. The second was conducted in the spring of 2013; it relied on a combination of FSU students and online participants drawn from a pool of paid subjects from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

The first experiment presented each subject with only one ballot measure. One group was presented with a ballot measure dealing with waste disposal and the other with a measure regarding school funding. Next, subjects were subdivided into treatment (specific language) and control (unspecific language) groups.

All subjects were told: “[m]any states offer ballot initiatives to allow voters to directly determine policy. We would like to know how you would feel about the following initiative if it were applied to where you live,” which was followed by one of four vignettes: a specific waste disposal measure, an unspecific waste disposal measure, a specific school funding measure, and an unspecific school funding measure.

By Another Believer (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Both of the ballot questions were taken from real measures that appeared on ballots in different states, and both parings of vignettes have the same tax amount. Finally, any county, city, or district names were changed to mimic real-world measures. After being presented with the measure, subjects were asked how they would vote: yes, abstain, or no.

We found that when subjects were given specific language about how their tax dollars will be spent, we saw a significant increase in the probability of voting yes.

Figure 1 shows what we found: subjects receiving the unspecific vignette (hollow circles) strongly opposed the waste measure (44 percent voting no, 29 percent abstaining; top figure), but were largely ambivalent on the school support measure (12 percent voting no, 66 percent abstaining; bottom figure). When provided with specific language about how the taxes will be utilized (solid circles), we see sizable changes in support. In fact, for both support for waste disposal and support for school funding we see voting pluralities becoming majorities: moving from 27 percent to 56 percent voting yes for waste disposal, and from 22 percent to 61 percent voting yes for school funding.

Figure 1 – Predicted probability of vote position for waste disposal and school funding measures

Note: Estimates represent the predicted probability with 95 percent confidence intervals, two-tailed. Solid circles represented the predicted values for subjects receiving the treatment.

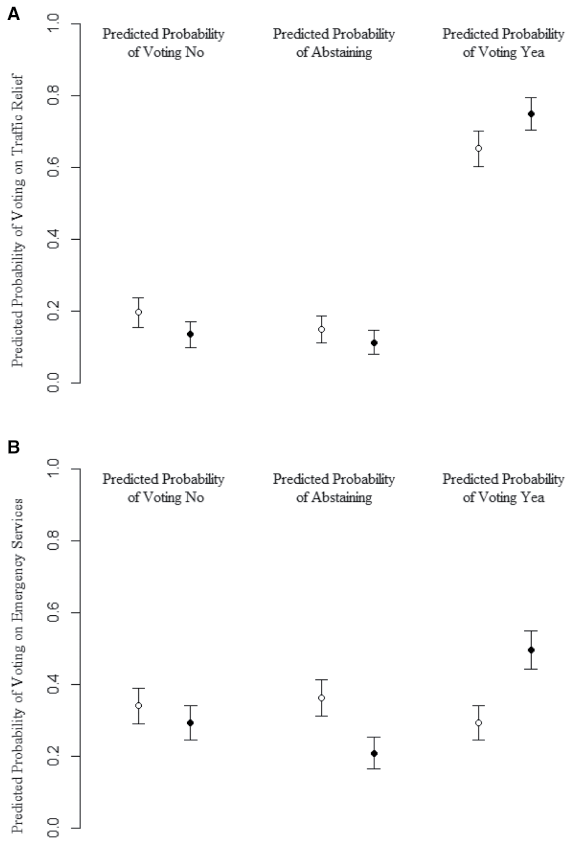

My second experiment introduced two new issue areas: traffic relief and access to emergency services, and utilized both student and nonstudent (Amazon’s MTurk) subjects.

Subjects were presented with the following question: “[h]ow you would feel about the following initiative if it were applied to where you live?” After which, respondents were randomly assigned one traffic and one emergency services vignette. As before, half were given the unspecific language, and the other half the specific language.

The top part of Figure 2 explores the results. Unlike the first experiment, the traffic relief measure found strong support in the specific and unspecific conditions. That said, the effect of the specific treatment frame was substantial. For those in the unspecific condition (hollow circles), we see that approximately 20 percent were opposed and 65 percent in favor; however, for those exposed to the treatment frame, we see opposition drop to 14 percent and support jump 10 points.

Figure 2 (bottom) shows that increased funding for emergency services was viewed with a great degree of opposition and ambivalence. For the unspecific frame, 34 percent opposed the tax, and 36 percent abstained; this left a mere 29 percent in favor. For those receiving greater specificity, we again see substantial changes in support: opposition drops slightly to 29 percent, support jumps to just shy of 50 percent, and abstentions plummeted to 21 percent. Although the specific language fails to give the emergency services measure majority support, we nonetheless see massive behavioral shifts.

Figure 2 – Predicted probability of vote for traffic relief measures and emergency services

Note: Estimates represent the predicted probability with 95 percent confidence intervals, two-tailed. Solid circles represented the predicted values for subjects receiving the treatment.

More details = more likelihood of success for ballot measures

State and local use of ballot propositions has become increasing common; currently, 38 states permit voters to make legislative decisions. In early 2018, there were already five state and local measures asking voters to pay additional taxes in exchange for various state-sponsored benefits, including police services, parks and recreation, and university support. Although there has been considerable work investigating ballot measures on matters such as language complexity, ballot design, voter awareness, and interest group endorsement, left unanswered is the role of specific language in altering support for ballot measures that require voters to pay higher taxes for more services.

My findings strongly suggest a relationship between using more precise language and increased support for ballot measures that levy a tax. This has potentially broad implications for citizen groups and politicians seeking to persuade voters to adopt policies, even when those policies come at a cost. In short, those wishing to increase support for a ballot measure that requires taxpayer support may do so by simply providing additional details on how the assessed taxes will be utilized.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘You Want to Spend My Money How? Framing Effects on Tax Increases via Ballot Propositions’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2DYDtiv

About the author

Travis Braidwood – Texas A&M University

Travis Braidwood – Texas A&M University

Travis Braidwood is an assistant professor of political science at Texas A&M University–Kingsville. He studies Congress, voter behavior, public opinion, political psychology, political methodology, and direct democracy.