Millions of Americans now experience economically insecure lives, often living pay check to pay check. Could improving people’s social capital – people’s trusted connections with one another – be one starting point to addressing this insecurity? In new research, Mallory E. Compton finds that social capital is actually linked with greater economic insecurity: where it is at its highest, nearly 18 percent of households are predicted to experience a substantial income loss in any given year. She points to the potential ‘dark side’ of social capital as one possible cause – strong bonds between the powerful can bring together resources to disadvantage already marginalised groups.

Millions of Americans now experience economically insecure lives, often living pay check to pay check. Could improving people’s social capital – people’s trusted connections with one another – be one starting point to addressing this insecurity? In new research, Mallory E. Compton finds that social capital is actually linked with greater economic insecurity: where it is at its highest, nearly 18 percent of households are predicted to experience a substantial income loss in any given year. She points to the potential ‘dark side’ of social capital as one possible cause – strong bonds between the powerful can bring together resources to disadvantage already marginalised groups.

Economic insecurity of American households has risen in recent decades (and to a lesser extent in other countries). People now experience more year-to-year volatility in household income than they have in nearly a generation. This trend raises important questions about how states and communities can protect households against economic risk.

One solution is public policy. Unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and need-based income support are public programs aimed directly at securing household-level economic stability. These programs transfer monetary or in-kind benefits to households to help replace lost income and provide services in times of need. And they’re effective: income security is greater in US states that spend more per capita on these kinds of social programs.

Another solution could be less formal: social capital. We hear about social capital on podcasts, we read about it in the news and in books (and more books), and there’s an effort to measure it worldwide. A common argument holds that where social capital is greater (i.e., where people are more trusting and more connected to one another), democratic governance (and public administration) will run more effectively and markets will operate more efficiently, thereby making communities more prosperous and resilient. Indeed, social capital has been linked to a range of organizational, economic, health, and educational outcomes—often these are beneficial outcomes, but sometimes they are not.

How does social capital work?

When social capital produces desirable democratic and economic benefits, it does so through a combination of effects. First is an informational effect: interpersonal networks and more frequent interactions may promote market efficiency, employment, and entrepreneurship by spreading information. Second is a direct assistance effect: the connectedness and norms of reciprocity of social capital may promote direct inter-personal assistance—neighbours help neighbours in ways that make life easier, healthier, and more productive. Third is an organizational effect: design and administration of public programs—and especially social programs—depend on coordination, planning, and communication across policymakers, administrators, and program recipients which might be more easily achieved with greater social capital.

Through these effects, social capital should better enable households (and communities) to maintain economic stability year-over-year. These effects don’t occur in all circumstances, however, and more and more research has shown that social capital often fails to deliver on its promises, or, worse yet, may have unequitable consequences.

Photo by Cindy Tang on Unsplash

In recent research, I examined whether social capital is related to economic (in)security in the US, and whether it makes a difference for the effectiveness of social programs. I used state-level annual measures of public spending, social capital, and economic insecurity (measured as the percent of state residents who lost at least a quarter of their income from the previous year) from 1986-2010 (see my full article and replication data for methodology details).

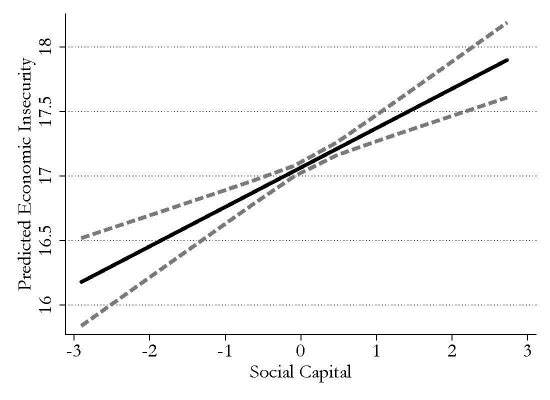

What I found is both disappointing and, perhaps, puzzling. First, my findings suggest that social capital is detrimental to economic security: even after controlling for other factors, states with more social capital experience significantly more economic insecurity. Figure 1 illustrates this finding. Where social capital is lowest, 16.2 percent of households are predicted to experience a substantial income loss in a given year. Where social capital is greatest, this number rises significantly to 17.8 percent.

Figure 1 – Effect of Social Capital on Predicted Economic Insecurity

Note: Dashed lines indicate 95 percent confidence intervals for predicted economic insecurity.

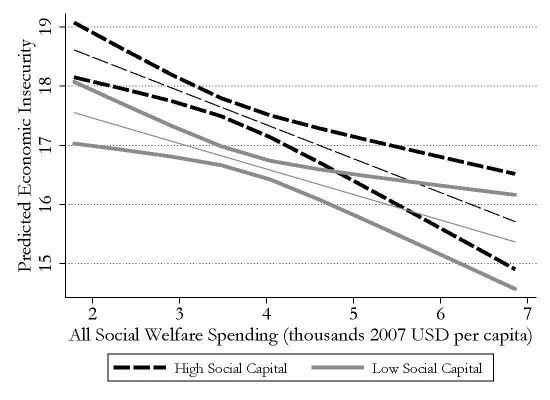

My second important finding is that dollar-for-dollar public spending on social programs is not more effective where social capital is greater (as some have argued). However, social capital has no significant effect in states that spend a lot on social programs, as shown Figure 2. Spending more on social welfare programs seems to mitigate the effect of social capital—public policy can overcome the detrimental impact of social capital on economic security.

Figure 2 – Effect of Total Social Welfare Spending on Predicted Economic Insecurity

Note. Each set of lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals for predicted economic insecurity under specified conditions.

Why social capital doesn’t always help

These data don’t allow me to identify the underlying processes causing these patterns (that would require a different research design and different data), but previous research points to some explanations for why social capital’s informational, inter-personal support, and organizational effects don’t always work for the benefit of everyone in a community.

The first is a structural explanation. If social capital ‘bonds’ (cements existing links within groups) more than it ‘bridges,’ (brings together different groups) its effects can be unequal because some (resource-rich) groups will benefit relatively more from trust and social ties. This is more likely to happen in more diverse communities, where interpersonal networks and connections are less likely to span across divisions in society.

A second explanation is perhaps more concerning: social capital has a ‘dark side’. Strong social bonds and the influence of social norms can mobilize resources to explicitly disadvantage marginalized or less advantaged groups. Social capital ‘resources’ can be co-opted towards undemocratic ends, or to shape policy rules for the exclusive benefit of some groups. It’s worth noting that cartels and organized crime also rely on trust and social networks to operate.

In the US context, these explanations mean that community-level social capital is often associated with positive outcomes among resource-rich or advantaged groups, while having a negative association with outcomes among disadvantaged or racial and ethnic minority groups. This might explain my finding that social capital increases overall economic insecurity at the state-level—but I can’t say for sure. With these data, it simply isn’t possible to identify what underlying forces cause these aggregate outcomes, nor can I identify the distributional consequences.

This leaves some important research questions that I (and others) will continue working on. Beyond identifying the contexts in which social capital helps or hurts, it’s vital to identify who is (dis)advantaged by it, to study what public programs or policy tools are most effective in ensuring economic security, and, to identify policy tools to mitigate the detrimental impact of social capital on economic security.

Rising economic insecurity is problem in the US, and Americans in states with more social capital experience more economic insecurity. The solution to economic insecurity is not more social capital. Greater state investment in social policies, however, does make a significant difference, not only by directly improving economic security, but also by mitigating the detrimental effect of social capital.

- This article post is based on the paper ‘Less Bang for Your Buck? How Social Capital Constrains the Effectiveness of Social Welfare Spending,’ in State Politics & Policy Quarterly, Volume 18, Issue 3, 2018.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2GVZVdK

About the author

Mallory E. Compton – Utrecht University

Mallory E. Compton – Utrecht University

Mallory E. Compton is a postdoctoral researcher at Utrecht University School of Governance. Her main research interests are public policy and governance performance, with a focus on social insurance and economic insecurity. Recent publications include an article in The Journal of Politics and a forthcoming book with Oxford University Press titled Great Policy Successes.