African Americans experience much higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and negative health outcomes compared to Whites in the US. Michael J Halloran writes that the intergenerational cultural trauma caused by 300 years of slavery – alongside poor economic circumstances and social prejudice – has led to the poor state of physical, psychological and social health among African Americans.

African Americans experience much higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and negative health outcomes compared to Whites in the US. Michael J Halloran writes that the intergenerational cultural trauma caused by 300 years of slavery – alongside poor economic circumstances and social prejudice – has led to the poor state of physical, psychological and social health among African Americans.

In his 1952 semi-autobiographical novel Go Tell it on the Mountain, the esteemed African American author James Baldwin asked the question “Could a curse come down so many ages? Did it live in time, or in the moment?” In my work, I argue that the curse of African American slavery cannot be underestimated; the trauma of enslavement has been carried by African Americans through the ages and generations and is currently shown in many of the health problems experienced by a significant proportion of the African American population in the US. My research focusses on how intergenerational trauma provides an important explanation for the persistence of health problems among African Americans; complementary to the more apparent negative impact of poverty and prejudice on health.

The success, wealth and notoriety of African Americans like Oprah, Obama, Beyonce and Michael Jordan masks the comparatively negative physical, psychological, and social health conditions of African Americans in general. For example, research shows the incidence of diabetes, high blood pressure, premature death from heart disease, and prostate cancer are generally double among adult African Americans compared to White Americans. African Americans experience significantly higher psychological stress and PTSD, and these are related to depressive symptoms, poor self-rated health, functional physical limitations and chronic illness. Similar comparisons of social health show homicide rates are higher, black men are 5 times more likely to be incarcerated than Whites (5 percent of the African American male population are incarcerated in many American states), and illicit drug use and rates of intimate partner violence are highest among African Americans.

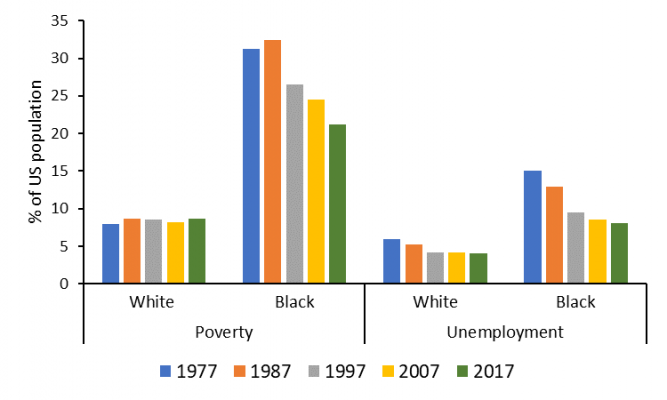

Two valid explanations for theses outcomes have received significant focus in the research literature: poor economic circumstances and social prejudice. Indeed, the poverty and unemployment rate among Black Americans has been at least double that of Whites over the last 40 years despite an overall decline (see Figure 1) and Blacks represent only 1.4 percent of the top 1 percent of households by income even though they comprise 13.6 percent of the US population. At the same time, research also clearly shows implicit prejudice is widespread in the US and related to negative health outcomes among African Americans like psychiatric symptoms, stress and cigarette smoking and a greater risk of heart attacks.

Figure 1 – Percentage of the US population in poverty or unemployed

Source: US Census Bureau and US Department of Labor

In line with these explanations, policy initiatives by successive American governments have sought to alleviate poverty, yet with short-lived success; the economic status of Black Americans and the economic inequality between Black and White Americans has changed little in the past 50 years. Similarly, it appears anti-discrimination laws and policies have been at best a limited solution to prejudice. For example, Black Americans are currently over-represented in the lower-paid service sectors, with lower job security, wages and benefits. And, African Americans still feel victims of prejudicial and unequal treatment as highlighted by the contemporary Black Lives Matter social movement.

Contemporary policies directed to address poverty and prejudice may have limited impact as they primarily target the injustices of today and do little to consider the impact of past injustices on the current state of African American health. My research focuses on how intergenerational trauma can help to explain the poor current health of African Americans. I argue that the historical legacy of enslavement and transmission of the associated cultural trauma is an important sociocultural perspective to understand the present generations of African Americans.

The notion of traumatic effects of enslavement being transferred to successive generations starts with the idea that slavery was not only a dreadful individual ordeal but a cultural trauma to African American people; a syndrome which occurs when a group has been subject to an unbearable event or experience thereby undermining their sense of group identity, values, meaning and purpose, or their cultural worldviews and is manifest in symptoms of hopelessness, despair and anxiety (notably, among Indigenous people subject to colonization and genocide and Holocaust survivors). Indeed, there was little value or meaning to African American lives under slavery; they were callously tied to their capacity for labor or ability to reproduce. Moreover, their identity was literally supplied by whoever happened to own them as though there was “not even a separate identity the ego can claim”. As the eminent African American essayist W.E.B. Du Bois claimed, African Americans were effectively banned from any pursuit of a cultural life through laws to prevent reading, writing and most communal life.

“slavery” by Bruno Casonato is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

At the same time, the symptoms of cultural trauma were evident during enslavement and found in many personal narratives from those times (e.g., Hannah Crafts, Frederick Douglas, Harriet Jacobs). Moreover, ongoing evidence of intergenerational trauma is then shown in the stories of many prevalent Black authors over subsequent years (e.g., Ernest Gaines, Zora Hurston, Richard Wright, Alice Walker). In Black Boy (1945), Richard Wright laments “My days and nights were one long, quiet, continuously contained dream of terror, tension, and anxiety. I wondered how long I could bear it”.

The contemporary situation of African American culture is viewed similarly and described as being practically on the edge of self-destruction; labelled as a collective pathology with respondents in a recent study claiming enslavement legacies impact on current-day African American psychological functioning. Research findings also shows high levels of accumulated trauma and hopelessness among African Americans are correlated with negative health outcomes (such as high blood pressure) and suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

The poor general state of African American physical, psychological and social health demands a comprehensive response from researchers, health practitioners, policy-makers and the community. The cultural trauma experienced by African Americans over the more than 300 years of their enslavement has been transmitted to the current generation and is related to their current general state of poor health. This perspective implies strategies to strengthen the resilience of African American cultural worldviews would remedy the negative impact of cultural trauma on their health. Indeed, interventions which harness cultural themes (e.g., racial, respect, cultural identity and values) act as a protective factor in the health of African Americans and significantly reduce anger and aggression in African American adolescent males.

Of course, the success of any strategy to alleviate intergenerational trauma and its effects needs to be considered in terms of the bigger picture of relations between Blacks and Whites in the US. The contemporary notions of collective responsibility for the past era of slavery and white privilege from the imposition racial inequality, however, is largely unacknowledged or resisted by most White Americans. As Martin Luther King put it: “When Negroes assertively moved on to ascend the second rung of the ladder, a firm resistance from the white community developed”. Nonetheless, research suggests one way out this dilemma is to emphasize a shared worldview and humanity between African and White Americans to reduce the impact of intergroup tensions. Martin Luther King advocated similarly when he argued for a human-rights approach to alleviating the poor social and economic conditions of African Americans. A human rights approach has the potential to heal the past Black and White relations in the US and nullify any resistance there may be to those who would seek to alleviate the negative effects of intergenerational trauma on the health and well-being of African Americans.

- This article is based on the paper ‘African American Health and Posttraumatic Slave Syndrome: A Terror Management Theory Account’, in the Journal of Black Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-8Dh

About the author

Michael Halloran – La Trobe University, Australia

Michael Halloran – La Trobe University, Australia

Dr Michael Halloran is an honorary associate professor at the School of Social and Public Health, La Trobe University, Australia. His research interests and publications focus on the role of cultural well-being in psychological and social health, reducing intergroup conflict, Indigenous Australian social justice, and intergenerational cultural trauma. Dr. Halloran has presented his work internationally and conducted research with a range of different cultural groups.

All ethnic groups have experienced some type of trauma/enslavement.at some period in history. I believe the underlying trauma for blacks in the US is the realization that there is no self organized defense against the internally and external forces that it faces daily basis.